The Sleepwalkers (116 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

They

were

also

called

the

"Pythagorean"

or

"Platonic"

solids.

Being

perfectly

symmetrical,

each

can

be

inscribed

into

a

sphere,

so

that

all

of

its

vertices

(corners)

lie

on

the

surface

of

the

sphere.

Similarly,

each

can

be

circumscribed

around

a

sphere,

so

that

the

sphere

touches

every

face

in

its

centre.

It

is

a

curious

fact,

inherent

in

the

nature

of

three-dimensional

space,

that

(as

Euclid

proved)

the

number

of

regular

solids

is

limited

to

these

five

forms.

Whatever

shape

you

choose

as

a

face,

no

other

perfectly

symmetrical

solid

can

be

constructed

except

these

five.

Other

combinations

just

cannot

be

fitted

together.

So

there

existed

only

five

perfect

solids

–

and

five

intervals

between

the

planets!

It

was

impossible

to

believe

that

this

should

be

by

chance,

and

not

by

divine

arrangement.

It

provided

the

complete

answer

to

the

question

why

there

were

just

six

planets

"and

not

twenty

or

a

hundred".

And

it

also

answered

the

question

why

the

distances

between

the

orbits

were

as

they

were.

They

had

to

be

spaced

in

such

a

manner

that

the

five

solids

could

be

exactly

fitted

into

the

intervals,

as

an

invisible

skeleton

or

frame.

And

lo,

they

fitted!

Or

at

least,

they

seemed

to

fit,

more

or

less.

Into

the

orbit,

or

sphere,

of

Saturn

he

inscribed

a

cube;

and

into

the

cube

another

sphere,

which

was

that

of

Jupiter.

Inscribed

in

that

was

the

tetrahedron,

and

inscribed

in

it

the

sphere

of

Mars.

Between

the

spheres

of

Mars

and

Earth

came

the

dodecahedron;

between

Earth

and

Venus

the

icosahedron;

between

Venus

and

Mercury

the

octahedron.

Eureka!

The

mystery

of

the

universe

was

solved

by

young

Kepler,

teacher

at

the

Protestant

school

in

Gratz.

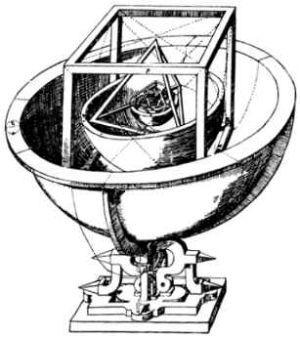

Model

of

the

universe;

the

outermost

sphere

is

Saturn's.

Illustration

in

Kepler

Mysterium

cosmographicum.

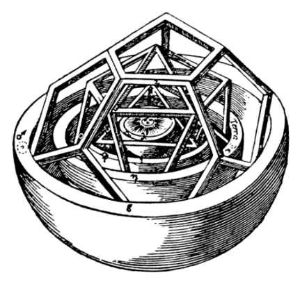

Detail,

showing the spheres of Mars, Earth, Venus and Mercury with the Sun in

the centre.

"It

is

amazing!"

Kepler

informs

his

readers,

"although

I

had

as

yet

no

clear

idea

of

the

order

in

which

the

perfect

solids

had

to

be

arranged,

I

nevertheless

succeeded

...

in

arranging

them

so

happily,

that

later

on,

when

I

checked

the

matter

over,

I

had

nothing

to

alter.

Now

I

no

longer

regretted

the

lost

time;

I

no

longer

tired

of

my

work;

I

shied

from

no

computation,

however

difficult.

Day

and

night

I

spent

with

calculations

to

see

whether

the

proposition

that

I

had

formulated

tallied

with

the

Copernican

orbits

or

whether

my

joy

would

be

carried

away

by

the

winds...

Within

a

few

days

everything

fell

into

its

place.

I

saw

one

symmetrical

solid

after

the

other

fit

in

so

precisely

between

the

appropriate

orbits,

that

if

a

peasant

were

to

ask

you

on

what

kind

of

hook

the

heavens

are

fastened

so

that

they

don't

fall

down,

it

will

be

easy

for

thee

to

answer

him.

Farewell!"

3

We

had

the

privilege

of

witnessing

one

of

the

rare

recorded

instances

of

a

false

inspiration,

a

supreme

hoax

of

the

Socratic

daimon

,

the

inner

voice

that

speaks

with

such

infallible,

intuitive

certainty

to

the

deluded

mind.

That

unforgettable

moment

before

the

figure

on

the

blackboard

carried

the

same

inner

conviction

as

Archimedes'

Eureka

or

Newton's

flash

of

insight

about

the

falling

apple.

But

there

are

few

instances

where

a

delusion

led

to

momentous

and

true

scientific

discoveries

and

yielded

new

Laws

of

Nature.

This

is

the

ultimate

fascination

of

Kepler

–

both

as

an

individual

and

as

a

case

history.

For

Kepler's

misguided

belief

in

the

five

perfect

bodies

was

not

a

passing

fancy,

but

remained

with

him,

in

a

modified

version,

to

the

end

of

his

life,

showing

all

the

symptoms

of

a

paranoid

delusion;

and

yet

it

functioned

as

the

vigor

motrix

,

the

spur

of

his

immortal

achievements.

He

wrote

the

Mysterium

Cosmographicum

when

he

was

twenty-five,

but

he

published

a

second

edition

of

it

a

quarter

century

later,

towards

the

end,

when

he

had

done

his

life

work,

discovered

his

three

Laws,

destroyed

the

Ptolemaic

universe,

and

laid

the

foundations

of

modern

cosmology.

The

dedication

to

this

second

edition,

written

at

the

age

of

fifty,

betrays

the

persistence

of

the

idée

fixe

: