The Sleepwalkers (115 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

____________________

* | The |

In

the

Preface

to

the

work,

Kepler

explained

how

he

came

to

make

his

"discovery".

While

still

a

student

in

Tuebingen,

he

had

heard

from

his

teacher

in

astronomy,

Maestlin,

about

Copernicus,

and

agreed

that

the

sun

must

be

in

the

centre

of

the

universe

"for

physical,

or

if

you

prefer,

for

metaphysical

reasons".

He

then

began

to

wonder

why

there

existed

just

six

planets

"instead

of

twenty

or

a

hundred",

and

why

the

distances

and

velocities

of

the

planets

were

what

they

were.

Thus

started

his

quest

for

the

laws

of

planetary

motion.

At

first

he

tried

whether

one

orbit

might

perchance

be

twice,

three

of

four

times

as

large

as

another.

"I

lost

much

time

on

this

task,

on

this

play

with

numbers;

but

I

could

find

no

order

either

in

the

numerical

proportions

or

in

the

deviations

from

such

proportions."

He

warns

the

reader

that

the

tale

of

his

various

futile

efforts

"will

anxiously

rock

thee

hither

and

thither

like

the

waves

of

the

sea".

Since

he

got

nowhere,

he

tried

"a

startlingly

bold

solution":

he

inserted

an

auxiliary

planet

between

Mercury

and

Venus,

and

another

between

Jupiter

and

Mars,

both

supposedly

too

small

to

be

seen,

hoping

that

now

he

would

get

some

sensible

sequence

of

ratios.

But

this

did

not

work

either;

nor

did

various

other

devices

which

he

tried.

"I

lost

almost

the

whole

of

the

summer

with

this

heavy

work.

Finally

I

came

close

to

the

true

facts

on

a

quite

unimportant

occasion.

I

believe

Divine

Providence

arranged

matters

in

such

a

way

that

what

I

could

not

obtain

with

all

my

efforts

was

given

to

me

through

chance;

I

believe

all

the

more

that

this

is

so

as

I

have

always

prayed

to

God

that

he

should

make

my

plan

succeed,

if

what

Copernicus

had

said

was

the

truth."

2

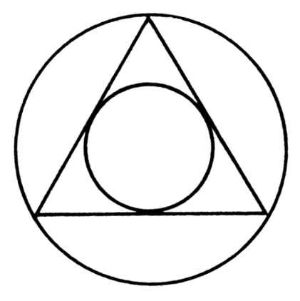

The

occasion

of

this

decisive

event

was

the

aforementioned

lecture

to

his

class,

in

which

he

had

drawn,

for

quite

different

purposes,

a

geometrical

figure

on

the

blackboard.

The

figure

showed

(I

must

describe

it

in

a

simplified

manner)

a

triangle

fitted

between

two

circles;

in

other

words,

the

outer

circle

was

circumscribed

around

the

triangle,

the

inner

circle

inscribed

into

it.

As

he

looked

at

the

two

circles,

it

suddenly

struck

him

that

their

ratios

were

the

same

as

those

of

the

orbits

of

Saturn

and

Jupiter.

The

rest

of

the

inspiration

came

in

a

flash.

Saturn

and

Jupiter

are

the

"first"

(i.e.

the

two

outermost)

planets,

and

"the

triangle

is

the

first

figure

in

geometry.

Immediately

I

tried

to

inscribe

into

the

next

interval

between

Jupiter

and

Mars

a

square,

between

Mars

and

Earth

a

pentagon,

between

Earth

and

Venus

a

hexagon..."

It

did

not

work

–

not

yet,

but

he

felt

that

he

was

quite

close

to

the

secret.

"And

now

I

pressed

forward

again.

Why

look

for

two-dimensional

forms

to

fit

orbits

in

space?

One

has

to

look

for

three-dimensional

forms

–

and,

behold

dear

reader,

now

you

have

my

discovery

in

your

hands!

..."

The

point

is

this.

One

can

construct

any

number

of

regular

polygons

in

a

two-dimensional

plane;

but

one

can

only

construct

a

limited

number

of

regular

solids

in

three-dimensional

space.

These

"perfect

solids",

of

which

all

faces

are

identical,

are:

(1)

the

tetrahedron

(pyramid)

bounded

by

four

equilateral

triangles;

(2)

the

cube;

(3)

the

octahedron

(eight

equilateral

triangles);

(4)

the

dodecahedron

(twelve

pentagons)

and

(5)

the

icosahedron

(twenty

equilateral

triangles).