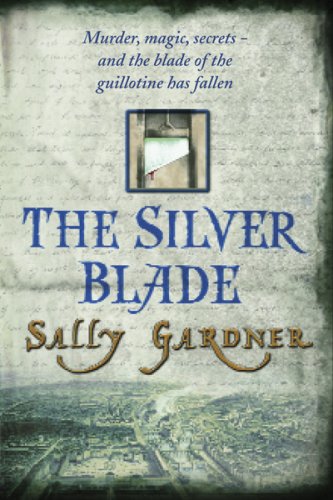

The Silver Blade

Table of Contents

Also by Sally Gardner

I, Coriander

The Red Necklace

The Red Necklace

The Silver Blade

SALLY GARDNER

Orion

An Orion Children’s ebook

First published in Great Britain in 2009

by Orion Children’s Books

a division of the Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper St Martin’s Lane

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

by Orion Children’s Books

a division of the Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper St Martin’s Lane

London WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright (c) Sally Gardner, 2009

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Orion Children’s Books.

The Orion Publishing Group’s policy is to use papers that are natural, renewable and recyclable products and made from wood grown in sustainable forests. The logging and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN : 978 1 8425 5736 5

This ebook produced by Jouve, France

For Judith.

I am the writer I am today because of you and for that I am eternally grateful. With your help and love I found my voice.

SG

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.

Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations

(1968)

(1968)

Prologue

T

here is no more terrifying a sight in all Paris than that of the guillotine. Never before has it been so easy to exterminate so many so quickly. Come rain or shine, come fog or snow, this indomitable killing machine is heedless of the weather or the passing seasons. It has no opinion of its victims or the number of times its blade is made to rise and fall in a single day. It is as blind to the innocent as it is to the guilty; both receive the same dreadful, swift punishment. Never before has Death walked with such an assured step as it does in these dark days of the Reign of Terror.

here is no more terrifying a sight in all Paris than that of the guillotine. Never before has it been so easy to exterminate so many so quickly. Come rain or shine, come fog or snow, this indomitable killing machine is heedless of the weather or the passing seasons. It has no opinion of its victims or the number of times its blade is made to rise and fall in a single day. It is as blind to the innocent as it is to the guilty; both receive the same dreadful, swift punishment. Never before has Death walked with such an assured step as it does in these dark days of the Reign of Terror.

The guillotine stands in the Place de la Revolution between the Garde-Meuble and the pedestal on which the Statue of Liberty has been erected. At night it is protected against the elements by a large canvas cloth tied fast with ropes. Even covered in its bloodstained winding sheet, it is a sight that inspires fear, and it is fear itself that like a contagious fever has taken hold of the city. It takes away all rational thought, bringing with it a delirium in which even your own shadow cannot be trusted. It spares neither the wise man nor the fool, the brave man nor the coward. Fear feeds on fear and, in March of 1794, it never goes hungry, for it is the devil’s own supper.

Midnight in Paris and the bells ring out the hour, each peal skimming like a pebble over the surface of the city. Not a peaceful lullaby to the end of the day, but a troubled warning: ‘Lock your doors, shut your shutters and hide.’

You can almost hear the universal prayer on every citizen’s lips: that the morning light might find them still asleep in their bed; you can never tell which door the National Guards will come knock-knock-knocking on next, whose name will be written in that little black book.

‘What’s that noise?’

‘There on the step.’

‘Who’s coming in at the gate at such an hour?’

‘Shh, listen, isn’t that the sound of boots upon the cobbles?’

‘Who’s next to be arrested?’

‘Did you hear that the seamstress was taken on the death cart only yesterday? Four children she leaves behind, orphaned.’

‘As long as it is not us.’

‘Quiet! What was that?’

‘Pull your sheets about your ears, go to sleep, my dear.’

Out there in this gated, barred and locked city, a foggy mist rolls up the Seine from Rouen, clinging like a lady’s veil just above the water line. It spreads into the narrow streets of the Place du Carrousel with its wretched hovels. Here lives Remon Quint. Once keymaker to the King, he sits in his tiny apartment regretting he hadn’t left Paris when he had the chance. Now, blowing out the candle on his way to bed, to lie tossing and turning in a dreamless sleep, he wonders if it is all too late.

The mist rolls on to spy into cracks and crevices as it makes its way up the pickle of streets, by the ruins of a church, past the riding-school, hanging like ghostly leaves on the rows of bare lime trees. In sight of the Tuileries Gardens, it lingers in the gutters, moving through the overcrowded slums where live the bird-sellers, the brokers, jugglers and dentists, quacks and dog gelders. Gathering strength round Loup’s butcher’s shop, with its sign of a black iron pig that wheezes on rusty hinges, it sneaks up to look in through the chink in the shutters. Madame Loup, the butcher’s wife, is all alone tonight. The two people she dreads most in the world, her husband and her son Anselm, are away from home. Where they are she doesn’t know, she doesn’t care. Lying in her wooden bed she dreams of her childhood, when she skipped barefoot through fields of sweet purple lavender, when the world was young and there still was hope.

In the Place de la Revolution, the moon has drawn back the heavy clouds which have been shading its mournful gaze to see, emerging from the shadow of the guillotine, Count Kalliovski. He is tall, meticulously dressed, but his clothes offer little protection against such an inhospitable night as this. And though a wind is beginning to chase the mist away, making a threadbare thing of the vapours, it blows not one item of his clothing.

If you were a mouse, and a brave one at that, you might have the courage to creep closer, for those are expensive riding boots he wears, that have to them a red heel. Whoever this man is - whatever this man is - he is reckless indeed to wear so openly such decadent symbols of aristocracy as red heels, black silk breeches and a silver buttoned waistcoat embroidered with tiny silver skulls. He has red kid gloves, the colour of poppies, his cravat is white as white can be, studded with a huge ruby pin like a single drop of blood. His coat collar rises to meet his hairline so that it looks as if his head is perched on, rather than connected to, his body. He appears to be a man of disjointed parts. But it is his face beneath the hat that makes all the rest quite forgettable. Those black eyes do not look human, so dark and dead, eyes from which no light shines. His skin is like tallow wax, his hair, swept back, is black, his lips a red wound. This is a face of nightmares.

K

alliovski goes walking here every night, the smell of blood drawing him time and time again to the guillotine. It is like a fine wine to his nose, a perfume to savour. He takes a last deep breath, inhaling the scent of death before setting off towards the Pont Neuf. He walks without a shadow to mark his passing.

alliovski goes walking here every night, the smell of blood drawing him time and time again to the guillotine. It is like a fine wine to his nose, a perfume to savour. He takes a last deep breath, inhaling the scent of death before setting off towards the Pont Neuf. He walks without a shadow to mark his passing.

On the shoreline of the Seine, near the Louvre, he stops and whistles. He hears the wolfhound before he sees him. Balthazar is no longer the loyal dog he once was. He looks larger, his fangs longer and sharper, his claws have the sound of iron in them. His coat is mangy, grown odd in patches, he lacks the grace that once was so natural to him. He lacks the devotion to his master that once marked him out.

On the south side of the river they make their way up to the rue St-Jacques. Here in a passageway lives Maitre Tardieu in his mole-like house. One miserable lantern lights his door. Kalliovski looks up at the shuttered window and wonders if the old lawyer knows where she is, and if he does, would he tell? It matters little. He will find Sido de Villeduval with the lawyer’s help or without it. Nothing will stop him.

His motto is and always will be the same: have no mercy, show no mercy.

Balthazar, restless to be gone, is at his master’s side as they set off together down the deserted streets of the rue Jacob. They alone inhabit the night, spectres of terror made visible, and Kalliovski revels in it. It has taken him time to accept that his power comes within the limitation of darkness. At the Place de Manon, Balthazar breaks away, howling, a sound which sends shivers down the spine of the living, a sound loud enough to wake the dead.

Kalliovksi calls him back, but the dog has vanished. Turning on his heel, he curses as he walks up the rue des Couteaux until at last he reaches a shop with three dimly lit red lanterns glowing in the window.

Inside the shelves are bare. But from behind the velvet curtain at the back a man appears, dressed from head to toe in black. Seeing his master he bows.

Other books

Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray

Broken Aro (The Broken Ones) by Wylie, Jen

Three Women of Liverpool by Helen Forrester

Shadows of Death by H.P. Lovecraft

First Lady by Michael Malone

Goldstone Recants by Norman Finkelstein

Undead for a Day by Chris Marie Green, Nancy Holder, Linda Thomas-Sundstrom

Rogue's Reward by Jean R. Ewing

A is for…

by

L Dubois