The Signature of All Things (25 page)

Read The Signature of All Things Online

Authors: Elizabeth Gilbert

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Foreign Language Fiction

On further consideration, though, Alma realized that she herself did not know in which variety of moss

Monotropa hypopitys

grew. On still further consideration, she realized that she was not entirely certain she could distinguish between different varieties of moss at all. How many were there, anyway? A few? A dozen? Several hundred? Shockingly, she did not know.

Then again, where would she have learned it? Who had ever written about moss? Or even about Bryophyta in general? There was no single authoritative book on the subject that she knew of. Nobody had made a career out of it. Who would have wanted to? Mosses were not orchids, not cedars of Lebanon. They were not big or beautiful or showy. Nor was moss something medicinal and lucrative, upon which a man like Henry Whittaker could make a fortune. (Although Alma did remember her father telling her that he had packed his precious cinchona seeds in dried moss, to

preserve them during transport to Java.) Perhaps Gronovius had written something about mosses? Maybe. But the old Dutchman’s work was nearly seventy years old by now—very much out of date and terribly incomplete. What was clear was that nobody paid much attention to the stuff. Alma had even chinked up the drafty old walls of her carriage house with wads of moss, as though it were common cotton batting.

She had overlooked it.

Alma stood up quickly, wrapped herself in a shawl, tucked a large magnifying glass into her pocket, and ran outside. It was a fresh morning, cool and somewhat overcast. The light was perfect. She did not have to go far. At a high spot along the riverbank, she knew there to be a large outcropping of damp limestone boulders, shaded by a screen of nearby trees. There, she remembered, she would find mosses, for that’s where she had harvested the insulation for her study.

She had remembered correctly. Just at that border of rock and wood, Alma came to the first boulder in the outcropping. The stone was larger than a sleeping ox. As she had suspected and hoped, it was blanketed in moss. Alma knelt in the tall grass and brought her face as near as she could to the stone. And there, rising no more than an inch above the surface of the boulder, she saw a great and tiny forest. Nothing moved within this mossy world. She peered at it so closely that she could smell it—dank and rich and old. Gently, Alma pressed her hand into this tight little timberland. It compacted itself under her palm and then sprang back to form without complaint. There was something stirring about its response to her. The moss felt warm and spongy, several degrees warmer than the air around it, and far more damp than she had expected. It appeared to have its own weather.

Alma put the magnifying lens to her eye and looked again. Now the miniature forest below her gaze sprang into majestic detail. She felt her breath catch. This was a stupefying kingdom. This was the Amazon jungle as seen from the back of a harpy eagle. She rode her eye above the surprising landscape, following its paths in every direction. Here were rich, abundant valleys filled with tiny trees of braided mermaid hair and minuscule, tangled vines. Here were barely visible tributaries running through that jungle, and here was a miniature ocean in a depression in the center of the boulder, where all the water pooled.

Just across this ocean—which was half the size of Alma’s shawl—she

found another continent of moss altogether. On this new continent, everything was different. This corner of the boulder must receive more sunlight than the other, she surmised. Or slightly less rain? In any case, this was a new climate entirely. Here, the moss grew in mountain ranges the length of Alma’s arms, in elegant, pine tree–shaped clusters of darker, more somber green. On another quadrant of the same boulder still, she found patches of infinitesimally small deserts, inhabited by some kind of sturdy, dry, flaking moss that had the appearance of cactus. Elsewhere, she found deep, diminutive fjords—so deep that, incredibly, even now in the month of June—the mosses within were still chilled by lingering traces of winter ice. But she also found warm estuaries, miniature cathedrals, and limestone caves the size of her thumb.

Then Alma lifted her face and saw what was before her—dozens more such boulders, more than she could count, each one similarly carpeted, each one subtly different. She felt herself growing breathless.

This was the entire world.

This was bigger than a world. This was the firmament of the universe, as seen through one of William Herschel’s mighty telescopes. This was planetary and vast. These were ancient, unexplored galaxies, rolling forth in front of her—and it was all right here! She could still see her house from here. She could see the familiar old boats on the Schuylkill River. She could hear the distant voices of her father’s orchardmen working in the peach grove. If Hanneke had rung the bell for mealtime at that very instant, she would have heard it.

Alma’s world and the moss world had been knitted together this whole time, lying on top of each other, crawling over each other. But one of these worlds was loud and large and fast, where the other was quiet and tiny and slow—and only one of these worlds seemed immeasurable.

Alma sank her fingers into the shallow green fur and felt a surge of joyful anticipation. This could belong to her! No botanist before her had ever committed himself uniquely to the study of this undervalued phylum, but Alma could do it. She had the time for it, as well as the patience. She had the competence. She most certainly had the microscopes for it. She even had the publisher for it—because whatever else had occurred between them (or had not occurred between them), George Hawkes would always be happy to publish the findings of A. Whittaker, whatever she might turn up.

Recognizing all this, Alma’s existence at once felt bigger and much,

much smaller—but a pleasant sort of smaller. The world had scaled itself down into endless inches of possibility. Her life could be lived in generous miniature. Best of all, Alma realized, she would never learn

everything

about mosses—for she could tell already that there was simply too much of the stuff in the world; they were everywhere, and they were profoundly varied. She would probably die of old age before she understood even half of what was occurring in this one single boulder field.

Well, huzzah to that!

It meant that Alma had work stretched ahead of her for the rest of her life. She need not be idle. She need not be unhappy. Perhaps she need not even be lonely.

She had a task.

She would learn mosses.

If Alma had been a Roman Catholic, she might have crossed herself in gratitude to God at this discovery—for the encounter did have the weightless, wonderful sensation of religious conversion. But Alma was not a woman of excessive religious passion. Even so, her heart rose in hope. Even so, the words she now spoke aloud sounded every bit like prayer:

“Praise be the labors that lie before me,” she said. “Let us begin

.

”

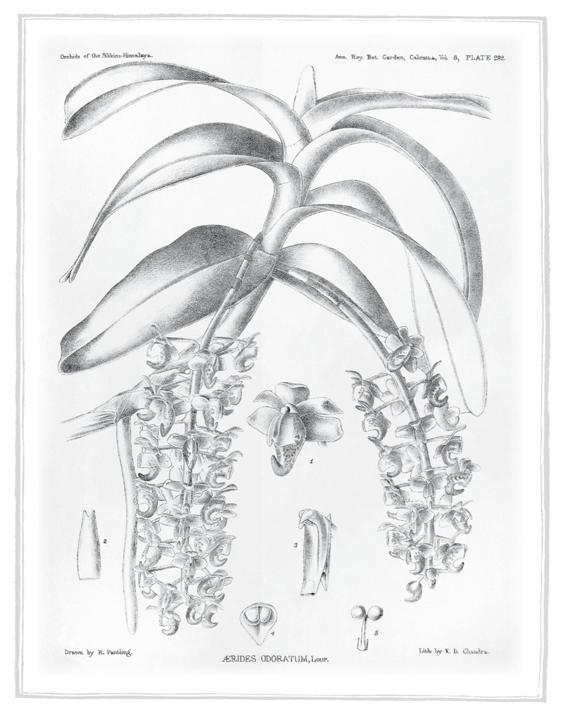

Aerides odoratum, Lour

PART THREE

The Disturbance of Messages

Chapter Twelve

B

y 1848, Alma Whittaker was just beginning work on her new book,

The Complete Mosses of North America.

In the previous twenty-six years, she had published two others—

The Complete Mosses of Pennsylvania

and

The Complete Mosses of the Northeastern United States—

both of which were long, exhaustive, and handsomely produced by her old friend George Hawkes.

Alma’s first two books had been warmly received within the botanical community. She had been flatteringly reviewed in a few of the more respectable journals, and was generally acknowledged as a wizard of bryophytic taxonomy. She had mastered the subject not only by studying the mosses of White Acre and its surroundings, but also by purchasing, trading, and cajoling samples from other botanical collectors all over the country and the world. These transactions had been easily enough executed. Alma already knew how to import botanicals, and moss was effortless to transport. All one had to do was dry it, box it up, and put it on a ship, and it would survive its journey without the slightest trouble. It took up little space and weighed virtually nothing, so ships’ captains did not mind having it as extra cargo. It never rotted. Dried moss was so perfectly designed for transport, in fact, that people had already been using it as packing material for centuries. Indeed, early in her explorations, Alma had discovered that her father’s dockside warehouses were already filled with several hundred

varieties of mosses from across the planet, all tucked into neglected corners and crates, all ignored and unexamined—until Alma had gotten them under her microscope.

Through such explorations and imports, Alma had been able, over the past twenty-six years, to collect nearly eight thousand species of mosses, which she had preserved in a special herbarium, stored in the driest hayloft of the carriage house. Her body of knowledge in the field of global bryology, then, was almost excruciatingly dense, despite the fact that she herself had never traveled outside Pennsylvania. She kept up correspondence with botanists from Tierra del Fuego to Switzerland, and carefully watched the complex taxonomical debates that raged in the more obscure scientific journals as to whether this or that sprig of

Neckera

or

Pogonatum

constituted a new species, or was merely a modified variation of an already documented species. Sometimes she chimed in with her own opinions, with her own meticulously argued papers.

What’s more, she now published under her own full name. She was no longer “A. Whittaker,” but simply “Alma Whittaker.” No initials were appended to the name—no evidence of degrees, no membership in distinguished gentlemanly scientific organizations. Nor was she even a “Mrs.,” with the dignity that such a title affords a lady. By now, quite obviously, everyone knew she was a woman. It mattered little. Moss was not a competitive domain, and that is the reason, perhaps, that she had been allowed to enter the field with so little resistance. That, and her own dogged perseverance.

As Alma came to know the world of moss over the years, she better understood why nobody had properly studied it before: to the innocent eye, there appeared to be so little

to

study. Mosses were typically defined by what they lacked

,

not by what they were, and, indeed, they lacked much. Mosses bore no fruit. Mosses had no roots. Mosses could grow no more than a few inches tall, for they contained no internal cellular skeleton with which to support themselves. Mosses could not transport water within their bodies. Mosses did not even engage in sex. (Or at least they did not engage in sex in any obvious manner, unlike lilies or apple blossoms—or any other flower, in fact—with their overt displays of male and female organs.) Mosses kept their propagation a mystery to the naked human eye. For that reason, they were also known by the evocative name Cryptogamae—“hidden marriage.”

In every way mosses could seem plain, dull, modest, even primitive. The simplest weed sprouting from the humblest city sidewalk appeared infinitely more sophisticated by comparison. But here is what few people understood, and what Alma came to learn: Moss is inconceivably strong. Moss eats stone; scarcely anything, in return, eats moss. Moss dines upon boulders, slowly but devastatingly, in a meal that lasts for centuries. Given enough time, a colony of moss can turn a cliff into gravel, and turn that gravel into topsoil. Under shelves of exposed limestone, moss colonies create dripping, living sponges that hold on tight and drink calciferous water straight from the stone. Over time, this mix of moss and mineral will itself turn into travertine marble. Within that hard, creamy-white marble surface, one will forever see veins of blue, green, and gray—the traces of the antediluvian moss settlements. St. Peter’s Basilica itself was built from the stuff, both created by and stained with the bodies of ancient moss colonies.

Moss grows where nothing else can grow. It grows on bricks. It grows on tree bark and roofing slate. It grows in the Arctic Circle and in the balmiest tropics; it also grows on the fur of sloths, on the backs of snails, on decaying human bones. Moss, Alma learned, is the first sign of botanic life to reappear on land that has been burned or otherwise stripped down to barrenness. Moss has the temerity to begin luring the forest back to life. It is a resurrection engine. A single clump of mosses can lie dormant and dry for forty years at a stretch, and then vault back again into life with a mere soaking of water.

The only thing mosses need is time, and it was beginning to appear to Alma that the world had plenty of time to offer. Other scholars, she noticed, were starting to suggest the same notion. By the 1830s, Alma had already read Charles Lyell’s

Principles of Geology

,

which proposed that the planet was far older than anyone had yet realized—perhaps even millions of years old. She admired the more recent work of John Phillips, who by 1841 had presented a geological timeline even older than Lyell’s estimates. Phillips believed that Earth had been through three epochs of natural history already (the Paleozoic, the Mesozoic, and the Cenozoic), and he had identified fossilized flora and fauna from each period—including fossilized mosses.