The Shadow Year (16 page)

Authors: Jeffrey Ford

Mary broke from the gate of her vacation like Pop's favorite horse, Rim Groper, and was all over Botch Town at least once a day. Whenever Jim and I went down into the cellar after our homework, all the figures would have moved. Mr. Felina was in his driveway, Peter Horton was on his way toward Hammond, and Mr. Curdmeyer was spending a lot of time in his grape arbor in the middle of winter. The first things we always checked for were the prowler and the white car. The prowler prowled up and down just outside the school while the white car passed Boris the janitor's house.

“He's in two places at once?” said Jim.

“He's got powers,” I said.

“Do you think he splits himself and one of him spies on people and the other kills them?” he asked.

“Probably,” I said.

We went back to looking for the right configuration that would tell us where Mr. White would strike next.

“What are we gonna do if we figure it out?” I asked.

“We'll need to do something,” said Jim.

We asked Mary about a dozen times how she figured the stuff out, and she just shook her head. Then one night when we were studying Botch Town, we heard Mrs. Harkmar's voice

from the other side of the cellar. She was explaining to Mickey and the other students how her system worked.

“This is very complicated, so if you feel stupid, it's okay,” said Mrs. Harkmar in a flat voice, like a robot. “First, they're off, and then you start countingâone, two, three, four, five, six, seven. Then one, two, three, four, five, six. Then one, two, three, four. One, two, three, four, five, six. Like that. Then you start to add a lot with multiplication. Fast and faster on the back turn. See them in your head. See it. They're coming into the home stretch. Follow each one. Where are they going? Will they win, place, or show?”

We heard the ruler hit the desk and knew that Mrs. Harkmar had finished the lesson.

Jim looked at me and shook his head. We laughed, but we made sure that Mickey couldn't hear us. A few minutes later, Jim put his hand in his pocket and pulled something out. “Oh, I forgot to show you this.”

He handed me what looked like a baseball card. It was a New York Yankee card, an old Topps. The player, a painting instead of a photo, was named Scott Riddley. He had a Krapp flattop haircut and a mustache, a glove on his right hand. It said he was a pitcher.

“I got that in Mr. White's garage,” he said. “It was leaning against one of those bottles of Mr. Clean.”

“Really?”

He nodded.

“It's old,” I said.

“From 1953,” he said. “I looked on the back.”

I never understood the stuff on the backs of baseball cards. “Where?” I asked.

He turned the card over and pointed at a number, and I nodded without really seeing it.

“Mr. White collects Mr. Clean bottles and old baseball cards,” he said.

“Yeah?”

“Well, go write it down,” he said, and pointed to the stairs.

I thought of Mrs. Harkmar's lecture the next night when my father got home from work early and decided it was time I learned math his way. We sat at the dining-room table, the red math book open in front of us. My father had one of his yellow legal pads on which he sometimes did problems for fun, and I had my school notebook. He gave me one of the pencils he collected. On his night job as a janitor at the department store, he sometimes found half-used pencils in the trash. He sharpened them till their points were like Dr. Gerber's needles. “These are good pencils,” he said.

I nodded.

When he wrote numbers, his hand moved fast and the pencil made a cutting sound. He crossed his sevens in the middle. We started with him asking me the times tables. I knew up to five, and then things went black. He asked me what was six times nine. I counted on my fingers, and at one point the digits in my head that I'd imagined as bundles of sticks turned into eyes. Rows of eyes, staring back at me. I figured in silence for a long time, feeling the right answer slip away. I gave my answer. He shook his head and told me, “Fifty-four.” He drew six bundles of nine sticks and told me to count them. I did. Then he asked me another one, and I got that wrong, too. He told me the answer. On the next one, he went back to six times nine. “Fifty-one,” I said. He got red in the face, yelled, “Think!” and poked me in the chest with his index finger.

By the time we got through with multiplication, he was sweating. We moved on to my homeworkâa word problem. Planes and trains all going somewhere at one hundred miles an hour, all leaving at different times, passing each other, laying over for fifteen minutes, with passengers A, B, C, and D, each getting off at Chicago or New York or Miami. I tried to picture it and went numb. My father drew an airplane with an arrow pointing forward. Then he drew lines like triangle legs to two

different spots I guessed were on the ground. He wrote out

“100 miles an hour.”

He connected the dangling legs of the triangle with a straight, slashing line. He wrote A, B, and C at its points, the top point being the plane. He wrote D outside the triangle and drew a box behind it and wrote

“Train Station”

in script.

He said, “How far is Chicago from New York, and what time will D meet C and A? Figure it out, and I'll be back in a little while.” He got up, went into the living room, and turned on the TV. I sat there looking back and forth from his drawing to the book. I couldn't make anything out of it and eventually had to look away. For a while I stared at the screaming faces made by the knots in the wood paneling. I looked out the window at the night and at the light over the table.

In the middle of the table was a brass bowl with fruit in it. There were some bananas, an orange, and two apples, and they were all going brown. Three teeny flies hovered above the bowl. I stared at it for a long time, too tired to think to look elsewhere. It was like I was under a spell. My arm came off the table, my hand holding the pencil straight out toward one of the apples. When I jabbed, I jabbed slowly, letting the pencil slide through the rotten outer skin and into the mush below. I stabbed that apple three times before I even knew I was stabbing it, so I stabbed some other fruit. The pencil made neat dark holes.

“What's your answer?” said my father, returning to the table.

“B,” I said.

I saw him glance over at the fruit. “What's this shit?” he asked, pointing at the brass bowl.

I said, “It went bad, and I wanted to warn people not to eat it, so I poked holes in it while I was thinking.”

He stared at me, and I had to look away. “Go to bed,” he said.

As I shuffled away from the table, I heard him crumple his drawing of the airplane triangle. “B, for âbone-dry ignorance,'” he said with disgust.

Up in my bedroom, the antenna was silent. Instead I imagined the aroma of Mr. White's pipe smoke. The smell was so strong I could just about see it. George was out of bed more than once, pacing the floor, sniffing the closet. The next morning came like a punch in the face.

Three nights in a row, we noticed that the white car was somewhere close to Boris the janitor's house. On the fourth night, it was parked in his driveway. Jim lifted the car out of Botch Town and said, “We have to do something now.”

“It's Boris?” I asked.

He nodded. “If we tell Mom or Dad, we'll get in trouble for not telling them sooner, and if we tell the police, we'll still get in trouble. We should call them and not say our names but tell them everything we know and who we think will be next. Then we hang up.”

“No,” I said. “If you call, they can trace it. I saw it on

Perry Mason.

We need to write a letter, no return address.”

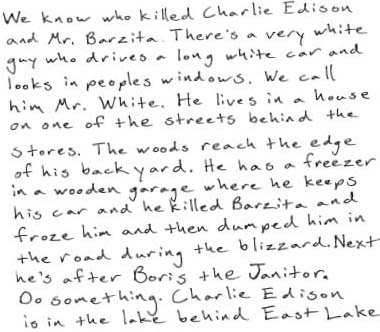

Jim liked the idea and told me to go get the notebook. I returned to the cellar, and he told me every word to write. Here's what he said:

I wrote as fast as I could, but my hand cramped. Jim finally took over and finished it. As he tore the letter out of my notebook, he said. “Let's send one to Krapp, too.”

“Same as the police?” I asked.

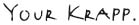

“No, I have a special message for him,” said Jim. He picked up the pencil and leaned over the notebook. He wrote only two words and then ripped the page out and held it up. In big, sloppy letters it read:

We laughed hard.

“His address is in the phone book,” Jim said. “Look it up for the envelope. I'll get the stamps.”

I took a deep breath when I went out to the mailbox on the corner. The street glistened under the light poles, and steam rose from the lawns. Taking a look up the block, I saw no headlights coming, so I started out at a slow jog. I had the two anonymous letters in my coat pocket, and I left the coat unzipped so as to run better. I made it to the corner halfway to Hammond in no time flat. The only thing that slowed me was the sight of

Mr. Barzita's house across the street. It crouched in the dark perfectly still behind a net of crisscrossing fig branches. When I reached for the handle of the mailbox, I looked down and saw what I thought was a clump of snow transform into a dead kitten lying on the frozen ground, its mouth open. It had sharp teeth, and its fur was pure white. A few inches away, someone had left a bowl half filled with milk, now frozen. I dropped the letters into the box and took off back home at top speed.

Nan reached way back into her bedroom closet and pulled out a long, dark brown billy club with a woven royal blue tassel around the handle. “That's the dress one,” she said. She handed it to Jim.

“Oh, man,” he said.

Mary reached for the tassel.

Nan went in for another and brought forth the club with the dice. It was shorter and blunter than the dress club, and blond in color. Inlaid into its side were two yellowed dice, showing six and one. She handed that one to me, and I could feel the energy go up my arm.

Next came the blackjack, shining like a scorpion, and Nan demonstrated on her palm, thunking it repeatedly with the rubbery weight. “You can break a skull with it,” she said. Jim reached for it, and Nan laughed. “Not on your life,” she said, and put it away.

Mary went over to look at the glass Virgin Mary filled with Lourdes water on the dresser, but Nan called her back and handed her a real police badge. Then, from out of her bathrobe pocket, she drew the police revolver. It had a wooden handle, and the rest looked like tarnished silver. She held it above our heads in her right hand, her grip wobbling. Jim's hand went toward it, and I ducked slightly. Mary held out the badge.

“You can't touch this. In case of an emergency, I keep it loaded,” Nan said.

“

You're

loaded,” Pop called down the hallway.

Nan laughed and put the gun away. She let us handle the clubs for another few seconds, and then when Jim made like he was going to crush my skull, she asked for them back. We couldn't believe it when she let Mary keep the badge.

“We'll split it,” said Jim.

Mary said, “No,” and left the bedroom. We heard the door to our house open and close, and she was gone. Nan gave Jim and me each a ladyfinger. We sat with Pop at the kitchenette table, where he smoked a Lucky Strike. Nan made tea and sat down with us.

After the drudgery of

Silas Marner,

Krapp dusted the chalk off his hands and stepped away from the blackboard. “It seems,” he said, “that someone has written me a letter.” His face flushed red, and his jaw tensed. When I heard the word “letter,” I almost peed my pants.

Don't look away

, I reminded myself.

“Someone has sent me a letter, I think, telling me who I am,” he said. He reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out a neatly folded square of notebook paper. He opened it and turned it to the class. We read it. Tim Sullivan had to cover his face with both hands, but no one made a sound. “I think it was one of you,” he said, staring up and down the rows into each person's eyes. “Becauseâ¦the writer missed the contraction.” When he got to me, I did my best not to blink.

“In fact,” he began, folding the letter and returning it to his pocket. He rubbed his hands in front of us. “I know who it was. You forget that I see your handwriting all the time. I took the letter and matched the handwriting to its author on one of your papers. Now, would the guilty party like to confess?”

I knew that Jim would never confess. He'd just sit there and nod slightly. That's what I intended to do, but inside I was getting weaker by the second. Part of me wanted so badly to blurt out that it was me. But then I realized that it really wasn't me, it

was Jim, and he wasn't even here, and that's when Krapp slapped his hands together and said, “Will Hinkley, come forward.” To hear it made me hollow inside, but I automatically laughed. No one even noticed me, because everybody had begun whispering. Krapp called, “Silence!”

“I didn't do it,” Will said, refusing to get out of his chair.

“Come up here now,” said Krapp. He trembled like George with a sneaker in his face.

“I didn't write you any letter,” said Hinkley, his Adam's apple bobbing like mad.

“I have the proof,” said Krapp. “Go to the office. Your parents are waiting there with Mr. Cleary.”

Will Hinkley got out of his seat, red in the face and with tears in his eyes. As he opened the door to leave the room, Krapp said to him, “No one tells me who I am, young man.”

“You're Krapp,” said Hinkley, and he ran down the hall, his sneakers squealing at the turn. The door swung shut, and Krapp told us to take out our math books.

All through the travels of A, B, C, and D from Chicago to New York at a hundred miles an hour, I thought about the cops opening the other letter. I saw them jump into their black-and-white cars, turn on the sirens, and then arrive at Mr. White's house. They crash in the back door, their guns out. Inside, it's dim and smells like Mr. Clean. They hear Mr. White escaping up the attic steps. By the time the cops reach the attic, all they find, in the middle of the floor, is a pillar of salt.

Jim didn't like it when I told him what happened. “That rots,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because now the cops are gonna think Hinkley wrote the other letter, too, and he'll get all the credit when they catch Mr. White.”

“We could have just told and gotten the credit,” I said.

“Yeah,” said Jim.

“Tim told me Hinkley's punishment is that he has to stay after school every day for the rest of the year and roll the trash barrels down to the furnace room,” I said.

“Hinkley can take the credit,” he said.

My mother had a bad night that night. She was fierce, her face puffy with anger. The air went thin, and it got hard to breathe. She was yelling insults at my father, cursing, drinking fast. My father sat at his end of the dining-room table, smoking a cigarette, head bowed. Mary and Jim headed for the cellar. I ran to my room, lay on my bed, and cried into my pillow. Her voice came up through the floor, a steady barrage that, like the blizzard, swelled into a howl, receded, and then swelled again. It went on and on, and I never heard my father say a word.

I eventually dozed off for a little while, and when I awoke, it was quiet. I got out of bed and carefully went down the stairs. The lights were out, and there was a lingering haze of cigarette smoke. I heard my father snoring from the bedroom down the hall. Going into the kitchen, I looked around in the dark for the bottle of wine. I found it on the sink counter and grabbed it by the neck.

At the back door, I undid the latch as quietly as possible, opened the storm door, and then pushed open the outer wooden door. Half in and half out of the house, one foot on the back porch, I heaved the bottle into the night. It clunked against the ground, but I didn't hear it break. When I turned back into the house, I jumped, because Nan was standing there in her bathrobe and hairnet.

“Go get it,” she said.

I started to cry. She stepped forward and hugged me for a minute. Then she whispered, “Go.”

I went out into the night in my bare feet and pajamas. It was freezing cold. I walked all around the area I thought the bottle had landed, but only when I stubbed my toe on it did I see it.

Back inside, Nan wiped the dirt off with a towel. I showed her where I'd gotten it from, and she replaced it on the counter. While she was locking the back door, she told me to go to bed.

Scenes from Perno Shell's adventures twined around my wondering what they had to do with Mr. White. I was almost certain from the smell of smoke that he'd read all the books I had. Either he just liked to read kids' books or it was a clue of some kind. But how could I know? The figures of Shell and Mr. White passed each other in the desert, on the Amazon. They became each other and then went back to being themselves in hot-air balloons. I saw them talk to each other, and then I saw them wrestle each other, Shell all in black and Mr. White in his overcoat and hat, on a rickety little bridge high above a bottomless lake.

“The Last Journey of Perno Shell,”

I said. George woke up, looked at me, and went back to sleep.