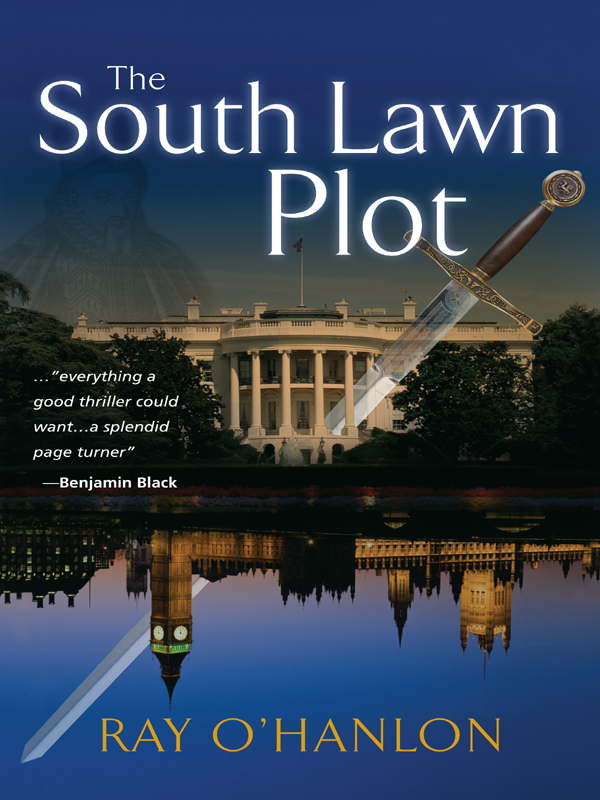

The South Lawn Plot

THE

S

OUTH

L

AWN

P

LOT

RAY O'HANLON

First published by GemmaMedia in 2011.

GemmaMedia

230 Commercial Street

Boston, MA 02109 USA

www.gemmamedia.com

© 2011 by Ray O'Hanlon

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner

whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews.

Printed in the United States of America

15Â Â 14Â Â 13Â Â 12Â Â 11Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â 1Â Â 2Â Â 3Â Â 4Â Â 5

978-1-934848-87-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data: O'Hanlon, Ray.

The South Lawn plot / Ray O'Hanlon.

p. cm.

Summary: “An international thriller that explores long-simmering religous conflict

and modern-day territory disputesӉProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-934848-87-6

1. JournalistsâFiction.  2. PresidentsâUnited StatesâFiction.   3. Prime

ministersâGreat BritainâFiction.  4. ConspiraciesâFiction.  5. Political

fiction. I. Title.

PS3615.H355S68 2011

813'.6âdc22

2010054379

For my family, in America and Ireland.

And for my father, Frank O'Hanlon (1926â2005)

B

AILEY WATCHED

as the smoke spiraled upwards and merged into the fog. Though it was officially spring, the temperature was purest January. He shivered. The light from the building and the street lamps by the dock gave the murk a yellowish hue. It was impossible to see beyond a few yards. Bailey sucked hard on his cigarette. He glanced at his watch and pressed the tiny knob that ignited the timepiece's internal light. It was twenty minutes to midnight. He would be done with his shift before the nicotine took full effect. For about ten seconds he ignored the vibrating of the cell phone in his pocket. He knew it had to be Henderson.

It was.

Henderson said nothing other than Nick Bailey's surname. That was all he needed to say.

Bailey drew his last satisfaction from the eroding stump of his filter tip, itself an insult to past generations of tabloid reporters who had turned newsrooms into toxic harbingers of global warming. Bailey wasn't impressed by the climate change theory. London, lately at any rate, seemed to have missed the phenomenon completely.

Turning into the doorway, he waved his security card in front of the scanner. The door opened, and he stepped into a foyer that was so brightly lit it might have been using half the city's electrical power supply. Bailey's eyes narrowed in the glare.

Beyond the lone security guard in his booth the place was empty. The front office, as it was called, had recently been redone. It was a homage to plastic; plastic tables and seats where people could wait to meet people from the offices on the upper floors and, of course, the newsroom, which was off limits to general visitors, yet another limit on the relaxed freedoms of a bygone time in the new age of security.

Framed front pages of the paper lined the walls. Some of them were undoubted classics, some dubious, and just a few plain tacky. The latest was

inspired by a simmering crisis between the western powers and China over Taiwan.

Beijing's foreign minister had recently been in London to meet his British counterpart. Britain had been told in no uncertain terms where it could consign its indignation. One of the paper's columnists had suggested, not entirely in jest, that Hong Kong should be retaken.

Bailey stared at the headline, a take on the Chinese minister's name. Not for the first time he smiled at “Chou Mean.”

Glancing at his watch, Bailey walked by the security guard. The man's eyes were fixed on a small television set that was showing an adult movie. Bailey shook his head. Godzilla could have been scampering around in the eight security monitors, and it would have made no difference.

Bailey covered the few paces to the elevator and pressed the button for the fifth floor. He cursed silently as, moments later, he stepped into the small hallway with the door leading into the newsroom of

The London Morning Post

.

As newsrooms went, the

Post's

was modest in size. Nevertheless its occupants considered themselves to have the edge over the city's rival tabs. But that edge had been sadly lacking on this night.

The first edition had carried a worthy but lackluster lead about health service cuts. The headline, “Hellth On Earth,” had been dreamed up in an effort to lift the story a bit. But Henderson had been muttering about the big one that was out there and had been clearly missed, not just by the

Post

, but by all the other tabs.

There was always an elusive big one as far as Henderson was concerned. And usually this Holy Grail of front-page spectaculars would be taking form between ten and midnight on a weeknight.

He wasn't always wrong. Throughout a career spanning more than forty years, Henderson had been proven correct in his assertion more times than any other tabloid deskman in London. He was sixty now and entitled to kick back a bit, but his energy for the mega scoops appeared undiminished.

Bailey was not alone in considering Henderson a little mad.

He had passed the lines of reporter's desks and was now standing in the little corral that housed the news editors, the beating heart of the

Post's

corpus.

It was also referred to by several other sobriquets, none of them polite. Right now, as far as Bailey was concerned, it was the rattrap. And he was playing the only rodent in sight. Percy Grace had somehow vanished.

Henderson was eyeballing the rival tabloid first editions. Bailey quickly dismissed their front-page leads from consideration; all but one. This one was trouble.

Henderson had scant time for the royal family. He was the newsroom's nearest thing to a resident republican and was never shy about showing his contempt for the monarchy, though he had sometimes displayed a softer spot for the dearly departed queen mum.

Henderson's antipathy towards matters royal had been attributed by those who cared to his birth in Quebec. Though he was not French Canadian, it was the common view that Henderson had been infected by French Canadian Anglophobia at an early age. Why else, it was asked, would he drink nothing but Cognac and keep a small plaster bust of Napoleon Bonaparte on his desk?

Yes, Henderson was just waiting for a chance to storm Buckingham Palace with a mob in tow and burn the pile to the ground. At the same time, and this was crucial to understanding what made the man tick, he was like a rabid dog when it came to royal stories, the more scandalous the better.

Henderson had the look of a man who had been sent to the newsroom by a kind of journalistic central casting. He was stocky, of middle height, balding and ruddy-faced. His sleeves, as far as Bailey could tell, had never been rolled down. His tie, his only tie, had a crest of a rugby club that had faded into history with the arrival of the professional game.

An older colleague had once told Bailey that Henderson was London's answer to Lou Grant. Bailey had nodded in the affirmative before checking out on his computer who the hell Lou Grant was.

No matter who he was like, or not like, Henderson had sniffed out some of the tabloid world's greatest hits on the royal family. In another time he would have long ago lost his head to the executioner's axe.

The only punishments he had suffered, however, was a dearth of invitations to royal events and a lengthy list of disdainful rebuttals from the palace to the scandals and affairs, some of them undoubtedly true, that he had splashed across the front page.

So here was the problem. It stared back at the glaring Henderson and now it reached out to the reluctant Bailey.

The Sun

had a whopper. One of the young royals, admittedly a second tier member of the family, was seemingly pregnant. And out of arranged wedlock.

The headline was no surprise in itself. It had probably taken a deskman at

the rival tab about three seconds to come up with “Princess Preggars.”The front page did not name the unfortunate royal. Finding out that gem would require lifting up the paper and turning inside. And that, of course, was a copy sold.

Oh, shit, Bailey thought.

The storm, however, did not follow. Henderson stared at the headline for a few moments and drummed the fingers of both hands on the desk. Then he turned, looked up at Bailey and delivered what passed for one of his rare smiles.

“We might have something better,” he said.

Bailey glanced at his watch. Whatever better was it would have to be already in the basket, more or less. Perhaps, he thought, old Percy Grace, the night reporter, and a man who looked like a survivor from the era of Lord Northcliffe, was working on the story this very minute.

Henderson let the moment linger. And then he let it out.

“Friend of mine on the force,” he said before pausing.

Oh, Christ, here we go, Bailey thought.

Henderson always referred to the police as the force. Not the plod, peelers coppers or filth. No such disrespect ever poured forth from the man's mouth. He had the utmost respect for the Metropolitan Police. And in fairness, the respect was returned from time to time. He seemed to have an army of sources in the ranks and the result had been occasionally startling.

“Yes,” Bailey said, a note of extreme caution in his voice. He had an idea what was coming next. It was something in the way that Henderson was leaning out of his chair towards him.

“A source,” Henderson said. “In the force.” He seemed pleased with the rhyme.

“Lestrade, perhaps?” Bailey was salvaging a smidgen of pleasure in referring to the bumbling inspector from the Sherlock Holmes stories. But he knew he was cornered.

Henderson ignored the jibe.

“There's a body hanging from Blackfriars Bridge,” he said. “A friend of mine, a source, is on the scene. His name is Tim Plaice. Detective Superintendent Tim Plaice.”

Bailey was momentarily surprised. Henderson did not usually put names on his sources. But then he understood. He, Nick Bailey, off home in a handful of minutes, was expected to plunge into the fog in search of this Plaice guy so as to lay claim to a body dangling from a bridge over the Thames.

“Somebody topped himself on the bridge,” said Bailey flatly. “Happens all the time. Three paragraphs on page nine.”

Henderson took in a breath that for a split second sounded like it might be his last.

“Think, Mr. Bailey, for God's sake,” he said. “A body on Blackfriars Bridge. Looks like a suicide, but a suspicious policeman has another idea swirling about in his highly attuned head”

“Okay, fine,” Bailey said in response, trying not to sound exasperated. “Six or seven pars on page four, no five, right hand page. It's late. There won't be much room for any more than that.”

Henderson leaned back. He was closing in for checkmate.

“Not if we ditch the lead, turn it into an inside short, open up the front page and run the new piece onto page two,” he said.

“All right,” said Bailey giving up. “You have me. What in the name of God is so big about a body hanging from a bridge? People throw themselves off bridges all the time. Bringing along a rope for the ride is a little unusual, I grant you, but not unknown. What are you sitting on?”

Henderson moved his queen, and Bailey, stuck fast and playing the role of cornered king, steeled himself for the

coup de grace

.

“The deceased is a priest,” he said. “And he's hanging off Blackfriars Bridge.”

“What?” said Bailey, not bothering to conceal his disbelief. “Stop the bleedin' presses for a pun! Have you been on the sauce?”

Bailey knew full well that Henderson was on nothing at the minute other than the printing ink that flowed through his veins.

“God give me strength.” Henderson almost snorted. “Where have you been all these years, Nick? Blackfriars Bridge. Nineteen eighty-two. Roberto Calvi. God's bloody banker.”

“Oh,” said Bailey. And that was all he could manage.

He suddenly felt very hungry. A vision of hot curried chips. It lingered for a split second before being blown away by Henderson who was now presenting him with a piece of paper with a scribbled headline.

“Nineteen eighty-two,” said Bailey. “I was still sucking my thumb. But the name Calvi does ring a bell. There's an Italian restaurant in Chelsea called Calvis I think, or maybe it's West Ken.”

Bailey had long ago learned never to admit to total ignorance. Every name rang a bell, especially if it came up in an exchange with Henderson.

Henderson, elbows on his desk and hands clasped, nodded.

“Every name rings a bell in your head, Nick. Think I didn't notice? You hear more bells than Quasimodo. Must be driving you round the bend by now.”

Bailey raised his eyes to heaven, or at least the strip lights that burned in the newsroom ceiling around the clock.

“Right,” said Henderson, “a quick lesson, so listen. And by the way I won't mind if you call in sick tomorrow night. I do owe you some hours.”

“Thanks,” said Bailey, though with little enthusiasm.

“Roberto Calvi, God's banker. Found hanging from Blackfriars Bridge, June of that year.”

Henderson had launched into one of his famous short hand briefings, the full intake of which was expected of all reporters at the

Post

, regardless of experience and tenure.

“Chairman of Banco Ambrosiano which was in much the same shape at the time as Calvi was after his leap. Huge debts in part due to murky dealings with the Vatican's version of the Bank of England, the Institute for Religious Works. Questions at the time of his death swirled around the Vatican, Mafia, freemasons, dodgy bankers and politicians and anyone in the building brick business.”

“The what?” said Bailey.

“Calvi's pockets and pants were stuffed with them. The force figured a suicide, but a few years ago there was a murder trial in Rome. So now you can see it, can't you? A priest dangling from Blackfriars. Chance to pad story from bottom with Calvi business. I'll get Percy to dredge it up. A new head, âDeadfriars,' or something on those lines. Better lead than health cuts. The taxi is waiting outside. Get something from the scene by one, one thirty at absolute latest, then piss off home.”

Bailey glanced at his watch.

“I'll call Percy on my mobile and just read over whatever I can get. He is here somewhere?”

Henderson nodded towards the gents.

“You said your friend's name was Plaice, Detective Superintendent Plaice?”

Henderson nodded again and returned to scanning the rival papers.

Bailey moved quickly towards the door. He looked at his watch again. It was two minutes after midnight. He was walking into a new day.

And, though he did not suspect it, another time.