The Secret History (53 page)

Read The Secret History Online

Authors: Donna Tartt

“Maybe something went wrong,” Francis said.

“Don’t be ridiculous. What could go wrong?”

“A million things. Maybe Charles lost his head or something.”

Henry gave him a fishy look. “Calm down,” he said. “I don’t know where you get all these Dostoyevsky sorts of ideas.”

Francis was about to reply when Camilla jumped up. “He’s coming,” she said.

Henry stood up. “Where? Is he alone?”

“Yes,” said Camilla, running to the door.

She ran down to meet him on the landing and in a few moments the two of them were back.

Charles’s eyes were wild and his hair was disordered. He took off his coat, threw it on a chair, flung himself on the couch. “Somebody make me a drink,” he said.

“Is everything all right?”

“Yes.”

“What happened?”

“Where’s that drink?”

Impatiently, Henry splashed some whiskey in a dirty glass and shoved it at him. “Did it go well? Did the police come?”

Charles took a long swallow, winced and nodded.

“Where’s Cloke? At home?”

“I guess.”

“Tell us everything from the first.”

Charles finished the glass and set it down. His face was a damp, feverish red. “You were right about that room,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“It was eerie. Terrible. Bed unmade, dust everywhere, half an old Twinkie lying on his desk and ants crawling all over it. Cloke got scared and wanted to leave, but I called Marion before he could. She was there in a few minutes. Looked around, seemed kind of stunned, didn’t say much. Cloke was very agitated.”

“Did he tell her about the drug business?”

“No. He hinted at it, more than once, but she wasn’t paying much attention to him.” He looked up. “You know, Henry,” he said abruptly, “I think we made a bad mistake by not going down there first. We should’ve gone through that room ourselves before either of them even saw it.”

“Why do you say that?”

“Look what I found.” He pulled a piece of paper from his pocket.

Henry took it from him quickly and looked it over. “How did you get this?”

He shrugged. “Luck. It was on top of his desk. I slipped it off the first chance I had.”

I looked over Henry’s shoulder. It was a Xerox of a page of the Hampden

Examiner

. Wedged between a column by the Home Extension Service and a chopped-off ad for garden hoes, there was a small but conspicuous headline.

MYSTERIOUS DEATH IN BATTENKILL COUNTY

Battenkill County Sheriff Department, along with Hampden police, are still investigating the brutal November 12 homicide of Harry Ray McRee. The mutilated corpse of Mr. McRee, a poultry farmer and former member of the Egg Producers Association of Vermont, was found upon his Mechanicsville farm. Robbery did not appear to be a motive, and though Mr. McRee was known to have several enemies, both in the chicken-and-egg business and in Battenkill county at large, none of these are suspects in the slaying.

Horrified, I leaned closer—the word

mutilated

had electrified me, it was the only thing I could see on the page—but Henry had turned the paper over and begun to study the other side. “Well,” he said, “at least this isn’t a photocopy of a clipping. Odds are he did this at the library, from the school’s copy.”

“I hope you’re right but that doesn’t mean it’s the only copy.”

Henry put the paper in the ashtray and struck the match. When he touched it to the edge a bright red seam crawled up the side, then licked suddenly over the whole thing; the words were illumined for a moment before they curled and darkened. “Well,” he said, “it’s too late now. At least you got this one. What happened next?”

“Well, Marion left. She went next door to Putnam House and came back with a friend.”

“Who?”

“I don’t know her. Uta or Ursula or something. One of those Swedish-looking girls who wears fishermen’s sweaters all the time. Anyway, she had a look around, too, and Cloke was just sitting there on the bed smoking a cigarette and looking like his stomach hurt him, and finally she—this Uta or whatever—suggested we go upstairs and tell Bunny’s house chairperson.”

Francis started laughing. At Hampden, the house chairpeople

were who you complained to if your storm windows didn’t work or someone was playing their stereo too loud.

“Well, it’s a good thing she did or we might still be standing there,” said Charles. “It was that loud, red-haired girl who wears hiking boots all the time—what’s her name? Briony Dillard?”

“Yes,” I said. Besides being a house chairperson and a vigorous member of the student council, she was also the president of a leftist group off campus, and was always trying to mobilize the youth of Hampden in the face of crushing indifference.

“Well, she barged right in and got the show on the road,” said Charles. “Took our names. Asked a bunch of questions. Herded Bunny’s neighbors into the hall and asked

them

questions. Called Student Services, then Security. Security said they would send somebody over—” he lit a cigarette—“but it really wasn’t their jurisdiction, a student disappearance, and that she should call the police. Will you get me another drink?” he said, turning abruptly to Camilla.

“And they came?”

Charles, cigarette balanced between his first and middle fingers, wiped the sweat from his forehead with the heel of his hand. “Yes,” he said. “Two of them. And a couple of security guards as well.”

“What did they do?”

“The security guards didn’t do anything. But the policemen were actually kind of efficient. One of them looked around the room while the other herded everybody in the hall and started asking questions.”

“What kind of questions?”

“Who’d seen him last and where, how long he’d been gone, where he might be. It all sounds pretty obvious but that was the first time anyone had even asked.”

“Did Cloke say anything?”

“Not much. It was very confused, a lot of people around, most of them dying to tell what they knew, which was nothing. No one paid any attention to me at all. This lady who’d come down from Student Services kept trying to butt in, acting very officious and saying it wasn’t a police matter, that the school would handle it. Finally one of the policemen got mad. ‘Look,’ he said, ‘what’s the matter with you people? This boy’s been missing for a solid week and nobody’s even mentioned it till now.

This is serious business and if you want my two cents, I think the school may be at fault.’ Well, that really got the lady from Student Services going and then, all of a sudden, the policeman in the room came out with Bunny’s wallet.

“Everything got very quiet. There was two hundred dollars in it, and all of Bunny’s ID. The policeman who’d found it said, ‘I think we’d better contact this boy’s family.’ Everyone started whispering. The lady from Student Services got very white and said she’d go up to her office and get Bunny’s file immediately. The policeman went with her.

“By this time the hall was absolutely mobbed. They’d trickled in from outdoors and were hanging around to see what was going on. The first policeman told them to go home and mind their own business, and Cloke slid away in the confusion. Before he left, he pulled me aside and told me again not to mention that drug business.”

“I hope you waited until you were told you could leave.”

“I did. It wasn’t much longer. The policeman wanted to talk to Marion, and he told me and this Uta we could go home once he’d taken our names and stuff. That was about an hour ago.”

“Then why are you just getting back?”

“I’m coming to that. I didn’t want to run into anybody on the way home, so I cut across the back of campus, down behind the faculty offices. That was a big mistake. I hadn’t even got to the birch grove when that troublemaker from Student Services—the lady who started the fight—saw me from out the window of the Dean’s office and called for me to come in.”

“What was she doing in the Dean’s office?”

“Using the WATS line. They had Bunny’s father on the telephone—he was yelling at everybody, threatening to sue. The Dean of Studies was trying to calm him down, but Mr. Corcoran kept asking to talk to someone he knew. They’d tried to get you on another line, Henry, but you weren’t home.”

“Had he asked to talk to me?”

“Apparently. They were about to send someone up to the Lyceum for Julian, but then this lady saw me out the window. There were about a million people there—the policeman, the Dean’s secretary, four or five people from down the hall, that nutty lady who works in Records. Next door, in the admissions office, somebody was trying to get hold of the President. There were some teachers hanging around, too. I guess the Dean of

Studies was in the middle of a conference when the lady from Student Services came bursting in with the policeman. Your friend was there, Richard. Doctor Roland.

“Anyway. The crowd parted when I came in and the Dean of Studies handed me the telephone. Mr. Corcoran calmed down when he realized who I was. Got all confidential and asked me if this wasn’t some type of frat stunt.”

“Oh, God,” said Francis.

Charles looked at him out of the corner of his eye. “He asked about you. ‘Where’s the old Carrot-Top,’ he said.”

“What else did he say?”

“He was very nice. Asked about you all, really. Said to tell everybody that he said hi.”

There was a long, uncomfortable pause.

Henry bit his lower lip and went to the liquor cabinet to pour himself a drink. “Did anything,” he said, “come up about that bank business?”

“Yes. Marion gave them the girl’s name. By the way—” when he looked up, his eyes were distracted, blank—“I forgot to tell you earlier, but Marion gave your name to the police. Yours too, Francis.”

“Why?” said Francis, alarmed. “What for?”

“Who were his friends? They wanted to know.”

“But why

me?

”

“Calm down, Francis.”

The light in the room was gone. The skies were lilac-colored and the snowy streets had a surreal, lunar glow. Henry turned on the lamp. “Do you think they’ll start looking tonight?”

“They’ll look for him, certainly. Whether they’ll look in the right place is something else.”

No one said anything for a moment. Charles, thoughtfully, rattled the ice in his glass. “You know,” he said, “we’ve done a terrible thing.”

“We had to, Charles, as we have all discussed.”

“I know, but I can’t stop thinking about Mr. Corcoran. The holidays we’ve spent at his house. And he was so sweet on the telephone.”

“We’re all a lot better off.”

“Some of us are, you mean.”

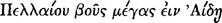

Henry smiled acidly. “Oh, I don’t know,” he said. “ ”

”

This was something to the effect that, in the Underworld, a

great ox costs only a penny, but I knew what he meant and in spite of myself I laughed. There was a tradition among the ancients that things were very cheap in Hell.

When Henry left, he offered to drive me back to school. It was late, and when we pulled up behind the dormitory I asked him if he wanted to come to Commons and have some dinner.

We stopped in the post office so Henry could check his mail. He went to his mailbox only about every three weeks so there was quite a stack waiting for him; he stood by the trash can, going through it indifferently, throwing half the envelopes away unopened. Then he stopped.

“What is it?”

He laughed. “Look in your mailbox. It’s a faculty questionnaire. Julian’s up for review.”

They were closing the dining hall by the time we arrived, and the janitors had already started to mop the floor. The kitchen was closed, too, so I went to ask for some peanut butter and bread while Henry made himself a cup of tea. The main dining room was deserted. We sat at a table in the corner, our reflections mirrored in the black of the plate-glass windows. Henry took out a pen and began to fill out Julian’s evaluation.

I looked at my own copy while I ate my sandwich. The questions were ranked from one—poor to five—excellent:

Is this faculty member prompt? Well-prepared? Ready to offer help outside the classroom?

Henry, without the slightest pause, had gone down the list and circled all fives. Now I saw him writing the number 19 in a blank.