The Road Narrows As You Go (32 page)

Read The Road Narrows As You Go Online

Authors: Lee Henderson

Wendy pulled aside the chef and said, Hey by the way, if you happen to have a spare raw egg â¦

In the middle of the meal Kravis stood to toast the to-be re-elected President Reagan, To the rubber ducky helping make us all rich fucks.

I'll drink to that, said Justine, waving her glass around, her eyes blinking out of unison this soon in the trip.

Cheers, said the rest of us. Even Jonjay said, He's a great father figure.

Wendy coughed. You bet he is.

He better be our man, said Piper Shepherd, considering the sizable contributions I made to his campaign.

I'm hiring more lobbyists to help my lobbyist, Frank said between bites.

Shepherd dropped his utensils. Are you telling me you

don't

have more than one lobbyist?

Oh my god, there's dessert, said Wendy, her hands on her stomach. Chef Lowenstein introduced us to an array of handmade chocolate mandelbrot, vanilla biscuits, lemoncakes, honeycakes, nunts, macaroons, fried bananas in caramel, and sugar doughnuts filled with blueberry slatko. Fruit picked that morning. Of course there was fresh-ground coffee percolating. And while we sat in our leather chairs eating all this fine food off all this polished silver, the blond interns from Israel poured us another glass of kosher wine. Then we sat back and watched the mountains of the Mojave Desert pass underneath the belly of the Gulfstream. We drew a breath.

Old movies are the junk bonds of television, Piper Shepherd said to Frank as we landed. Best thing I ever bought was the Looney Tunes catalogue.

Oh, wow, you own Looney Tunes? Wendy said. Don't you just want to watch them all day long?

Diabolical piffle, said Piper Shepherd, celebrating chaos, violence, vengeance, vandalism, and lawlessness. Corrupting those who have yet to be trained on even the basics of the toilet. That's what they said about Looney Tunes when I was a kid. But hell be damned they are funny and worth almost forty million to me in broadcast rights every fucking college semester. Can you count that? Forty, Frank. Forty. Imagine the money we would rake if I owned virtually

every

American movie made before nineteen sixty-fucking-nine because that's the kind of deal I'm

sitting on here, Frank, the rights and reels to ninety-nine percent of movie classics.

What do you need? Frank said as he broke off some sugar-glazed nunt and ate it, speaking while chewing, seeing how much of this Kravis was hearing, which seemed to be nothing, since he was asking Wendy for her number.

Seven hundred million dollars, Piper whispered.

20

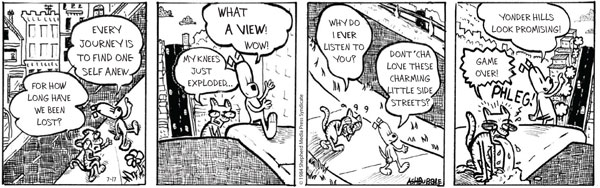

STRAYS

The trifling conversations that had taken up our time in the cabin of the Gulfstream evaporated in the heat. We were all alone in the baking desert with ourselves.

The landscape was so unlike the coast. Dry, dusty, and searing hot. There wasn't anything green in sight.

We seemed to have boarded some kind of kosher spaceship and in less than an hour hyperjumped to a farflung planet in another galaxy, with an atmosphere like our own but without any moisture in it. We stood in the

crackling heat. The clay pebbles on the ground broke easily beneath our shoes into ash. The mountains around us looked like smouldering piles of coal in a giant firepit.

You got ten more minutes of two-lane blacktop, said the man who greeted us at the airport in Stovepipe Wells, pointing a long, sinewy finger due east. After the turnoff you're going down one lane of gravel for 'nother forty minutes, okay, but that road winds around the valley and takes you all the way to the playa.

We convoyed in two Jeeps Frank had rented ahead of time. Jonjay drove the Jeep in the lead, he said he knew where to go, and Wendy, trusting in him, followed behind and chewed her teeth. Off we went. To our right were the Funeral Mountains and the Kodachrome Basin State Park. To our left were the Cottonwood Mountains and the Racetrack Playa. It was hot in the shade. We had the air conditioning blowing. We took Scotty's Castle Road just like the man told us to, a single lane of gravel that bummed along through the flat wide valley of pale Martian borax and dolomite until the Cottonwoods mellowed out into soft, very high hills. The undulating rifts of the blond-white borax formed deep-riven troughs between bladethin peaks. The scrub shaded the Cottonwoods above these dunes. The rock was striped with rusty pink belts.

Our Jeeps passed alluvial fans spreading jewelled pebbles down the mountainsides. At Death Valley Junction, shadeâtaking as many pictures as we could of these eerie cones and tides of red-and-white rock, like sleeping dragons with swollen bellies covered in boiling-hot sandâthe heavens granted us a penny-sized cloud.

From the overpoweringly conspicuous lavishness of Fleecen's private jet to the bedrock of this vaporous toaster, inhabitable only by coyotes, roadrunners, snakes, lizards, spiders, and other bloodsucking vermin immortalized in cartoons, we were glad our Jeeps sealed us in, cold and protected.

Driving about five miles an hour through narrow crevasses in the rock, we saw a gaunt hare with veined ears like lacrosse sticks do nimble

sporting herd movements. The tiny haggard Joshua trees that populated the many nooks and shelves were like pencil sketches of biblical wisemen stooped over against the howling heat. And the chuckwalla lizard we saw was unreal, more like a medieval symbol not meant to be taken literally. Above us the enormous sun exploding over the mountains sent fuggy overripe heat down to our level.

Piper Shepherd asked if we were circling around and around a burning maze or if we would ever breach this crack. Death Valley, what sort of game are you playing here? he said.

Not me, Kravis said, rubbing his hands together. I love these tiny gaps we're skating through, this is my mien, these tight narrow margins.

Very outer space, said Mark Bread with his nose to the window.

Kravis sniffed him. Who the fuck is the source of that B.O. smell that's floating around? It's asphyxiating.

That's me, Mark said, and giggled. Justine asked me to bring some from the hamper. He enigmatically patted his pocket.

If

she's

in then so am I, said Kravis, slapping his own cheeks.

Frank's wife told Jonjay to stop the Jeep. She was getting out. She trotted off down the road to the second Jeep and Wendy stopped driving and leaned out the window and asked her what she could do for her.

Someone trade seats with me for a while, Sue said. I'm tired of hearing those men and their euphemisms. One of them claims he can do fifty pushups the other claims he only eats doughnuts. And the little one is a crab.

I'll go sit with the boys, said Justine, no problem. I can dish it out.

You don't want to do that. That man Kravis is an asshole, Sue said as she buckled on a seatbelt. I kind of wanted to strangle him.

Who

is

he? Wendy said. Why is he here?

This is the first time I've met him, Sue said. However, she'd heard Frank complain about him for years. Quinn Kravis was a pseudoclient of Frank's who raked in millions exploiting tiny fluctuations in the exchange

rates of international currency. Say there's a spike in U.S. currencyâhe'd buy half a million British sterling and wait for the markets to back out and then sell the pounds at a tidy profit. Son of a laundromat owner, Kravis married richâHala Kravis was the daughter of Jamal Shahbandar, the Middle Eastern scientist who'd made his fortune selling chemical weapons like cyclosarin and VX to the Ba'ath regime in Iraq, before going into hiding in of all places Hoboken, New Jersey. Hala, an Iraqi-American glamour model in the pages of

Vogue Italia

at fifteen, met Kravis at a benefit for the Frick Collection when she was twenty-two, would bear him three children and call an eleven-bedroom estate in Westchester County home, with its mob neighbours and melancholy view of white sand and slate-grey Atlantic squalls. On their wedding night, Hala floated Kravis a million dollars of Shahbandar family money to start his private arbitrage equity firm, and after sex, instead of a cigarette, he started trading from the phone on the nightstand in their Beverly Hills honeymoon suite. Over six years as an arb scalping millions off the world financial market's minor discrepancies, Kravis had managed to rope Hala's entire inheritance into his investment stableâthis family's billion, plus the investors Kravis persuaded to throw millions more at his feet before he rolled the dice, made his arbitrage office one of the biggest bullies of Wall Street.

A truly toxic personality, Sue said. Frank meets the worst sorts of menâgreat for my fiction, awful for real life. Socially, cretins. Even the Feds think Kravis is up to no good. He's in the paper quoted saying greediness is next to godliness. He's a dracula. Bet you he's hitting on Justine as we speak.

What we saw when the mountains of Death Valley finally separated was this: Racetrack Playa's flat white surface shimmering with blue heatwaves for miles around, like a giant skating rink or a lake, an enormous mirror. We got out of the Jeeps and took our first tentative steps along the surface, cracked into plates of dried mud. The wind blew in our ears. Purgatory.

No one else around. Silence. Inside the bowl of time. Flat. Totally flat. For three miles in all directions. A frying pan. Surrounded on all sides by the rust-red Cottonwood Mountains shimmering in the heat. A blue dome over us. This intricate mosaic under our feet. The playa was cracked into hundreds of thousands of hexagonal tiles. A beautiful network of clay tiles made in extreme conditions. The air smelled of sand. The heat was an inescapable, dusty. Breathing burned. We did not adapt. Stunned, we spread out across the playa together and alone, toured the flatland from end to end, becoming dots to one another, to ourselves, our bodies becoming then vanishing, becoming again, then dots within our minds the longer we spent walking the Racetrack Playa.

What interested Jonjay about the playa was the sailing stones. These were practically the only other objects around to disturb the flat playa besides us, and we could see them coming from far away. There on the blank slate of the playa were inexplicably dozens of huge stones, and not only that, these stones had somehow, over time,

moved

, and left behind irregular swooping meandering paths in the dried mud, like drunk stones out for a stroll. Some of these stones had moved hundreds of feet across the basin.

Jonjay wanted to use large sheets of archival newsprint to do rubbings of the tracks, to record the movements of the stones as accurately as possible. Each stone might need fifty or more sheets of paper to get a complete rubbing of the entire path, which is what he wanted. The tracks behind the stones weren't elegant, these weren't tricks like the eerie mandalas found in crop circles. The stones indented the hardpacked snakeskin ground in aimless zigzags. No pattern at all. There were dozens of stones, hundreds of feet of paths to cover. This might take him more than an hour.

Hold on a minute, Rachael said. How many stones to you want to trace? Surely not all of them?

And how do you expect me to show these? My gallery isn't infinitely big. You waited years for

this

? You're never not infuriating.

Justine stood with her hands at her hips and watched as her artist got down on his hands and knees with a stack of paper and a box of charcoal and began to trace the long, chaotic lines. He wanted us to move methodically from the start of the stone and down along each long track, page after page, capturing as much of the detail as possible of the depressed mosaic floor of the playa.

Sue hugged herself and said, I would feel safer if I had on an astronaut's suit.

Frank got down on his hands and knees to help Jonjay. People push these around on a prank, right? he said. How else does a rock move?

That's what I say, too. People pushing. Justine turned her back to the wind so her hair flew in front of her face and she squeaked every time a pebble nipped at her calves. Eek! Beam me up, Scotty. I hope someone remembered to bring a bottle of something strong to this planet. She opened her purse and took out a forty of vodka. Ah, there we go. Mark, care for a swig?

She and Mark proceeded to get lit.

The temp was hovering in the hundred-and-one territory. It was October. The sky looked chlorinated.

Possibly pushing, Jonjay said and handed Frank a stack of paper. Plenty of theories flying around. But if you try pushing one now, it won't be easy to, and it won't leave behind the same kind of groove. And that's a lot of stones to push aroundâlook, there's dozens of them out here. Who's going to do that? For hundreds of years? The pioneers who came through here wrote about it in their diaries.

Then what is it? Frank was doing as told, doing a charcoal rubbing of the trail next to Jonjay's.

Some say aliens. We're a few hours' drive from Area 51. But what kind of dunce alien communicates via dolomite in an uninhabitable desert? Special magnetic force field maybe. Except dolomite isn't magnetic.

Telekinetic spy training ground, said Mark.

Might be. I'm with those who say natural phenomena. Rain. Ice. Frost. Wind.