The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire (2 page)

Read The Rise of Rome: The Making of the World's Greatest Empire Online

Authors: Anthony Everitt

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Then followed the

nomen

, or family name, the equivalent of our surname. After this came the

cognomen

. Originally, this was a nickname attached to a particular person (thus

Cicero

means “chickpea” and presumably referred to a pimple on the face of a once-upon-a-time Tullius), but over the years it came to denote branches of the larger family, or clan. A successful general would be given an additional cognomen, or

agnomen

, which referred to the enemy he

overcame. So, after defeating Hannibal in northern Africa, Publius Cornelius Scipio became Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus.

The subordinate status of women was exemplified by the fact that they were allocated only one name, the feminine version of the family nomen. So the daughter of Marcus Tullius Cicero was called Tullia. Sisters had to share the same name, which must have caused confusion in the family circle. They usually kept their

nomina

after marriage (so Cicero’s wife was called Terentia, not Tullia).

When using his full official designation, a Roman citizen inserted after his nomen his father’s praenomen and his tribe. So the complete Cicero was Marcus Tullius M[arci]

f

[

ilius

, or “Marcus’s son”] Cor[nelia

tribu

, “in the Cornelia tribe”] Cicero.

When readers use this book’s index, they should refer to the nomen. So when looking up Cicero, they will find him listed under the

T

’s as Tullius Cicero, Marcus. Tiresome, but that is how it is.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Preface

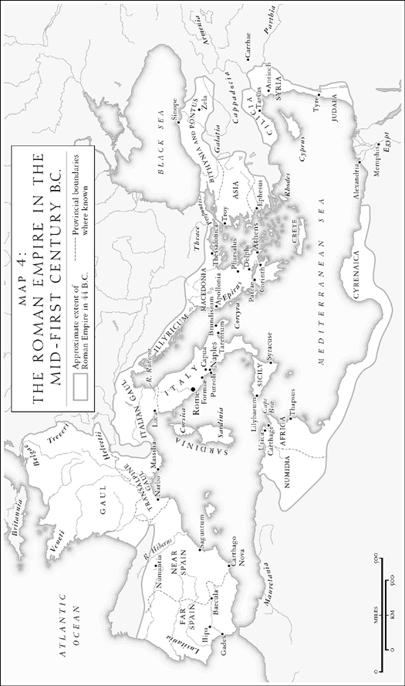

Maps

Introduction

I. LEGEND

1. A New Troy

2. Kings and Tyrants

3. Expulsion

4. So What Really Happened?

II. STORY

5. The Land and Its People

6. Free at Last

7. General Strike

8. The Fall of Rome

9. Under the Yoke

III. HISTORY

10. The Adventurer

11. All at Sea

12. “Hannibal at the Gates!”

13. The Bird Without a Tail

14. Change and Decay

15. The Gorgeous East

16. Blood Brothers

17. Triumph and Disaster

18. Afterword

Photo Insert

Time Line

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Sources

Bibliography

Notes

Other Books by This Author

About the Author

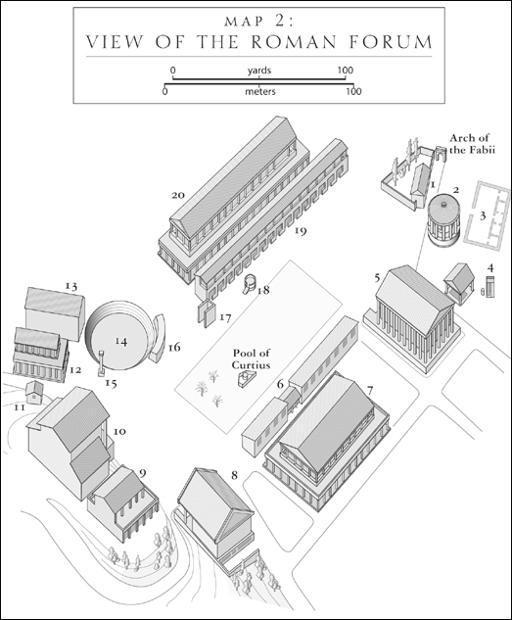

A reconstruction of the Roman Forum in the second century. Beginning from the top right, then clockwise. The triangular Regia (1); the circular temple of Vesta (2); in plan the House of the Vestals (3); the Pool of Iuturna (4), a long narrow trough; the temple of Castor and Pollux (5); the Old Shops (6), a row in front of the Basilica Sempronia (7); the temple of Saturn (8), Rome’s treasury; the Basilica Opimia (9); the temple of Concord (10); the tiny state Prison (11); the Basilica Porcia (12); the Senate-House or Curia (13), which looks out on the circular Comitium (14), a gathering place for meetings of the People’s assembly; the Column of Gaius Maenius (15), victor of a naval battle against Antium in 338; the speakers’ platform or Rostra (16), named after captured ships’ prows from Maenius’s victory; the shrine of Janus (17); the shrine of Venus Cloacina (18); the line of New Shops (19), behind which stands the Basilica Aemilia (20).

INTRODUCTION

T

WO OLD FRIENDS, NOW GETTING ON IN YEARS, WERE

looking forward to meeting each other again. The year was 46

B.C

. and Marcus Terentius Varro, the most prolific author of his day, was on his way to his country house a few miles south of Rome. A shrewd, practical man, Varro was no deep thinker, but he did try to know all that was known. His neighbor Marcus Tullius Cicero was a great public speaker, whether in the law courts or in the political bear pit of the Senate House. Self-regarding, eloquent, and sensitive, Cicero was vinegar to Varro’s oil. For all that, they liked each other, largely because they shared the same interests. One of these was a passion for Rome’s past.

By a happy chance, a few of Cicero’s letters to Varro have survived the bonfire of time. In one note, Cicero urged Varro to hurry up: “

I am coming to hope that your arrival is not far away. I wish I may find some comfort in it though our afflictions are so many and so grievous that nobody but an arrant fool ought to hope for any relief.”

The “afflictions” Cicero had in mind stemmed from a civil war among Rome’s governing élite. Leading personalities were at risk of losing life and limb. What were they to do, they asked themselves anxiously, in an age when the Roman Republic, the ancient

world’s lone superpower, omnipotent abroad, seemed bent on destroying itself at home?

MOST OBSERVERS OF

the day thought that the rot had set in a century or so previously. Rome’s conquest of Greece and much of the Near East released unimaginable quantities of gold, not to mention that human gold, uncounted numbers of slaves. Wealth flooded into Rome, which became, in effect, the capital of the known world and grew into a multicultural melting pot and megalopolis of up to one million souls.

This was the unintended consequence of winning an empire, and it is perhaps no accident that the serious study of Rome’s past began at about this time. To men like Varro and Cicero, the once tough, socially responsible, resourceful, and plain-living Roman was being softened and subverted by the Oriental vices of greed, luxury, and sexual license. The city’s constitution had served it well for centuries. A lawmaking citizens’ assembly balanced a small ruling class of nobles. But for this system to work effectively a capacity for compromise and reasonableness was essential—and now this capacity had been lost.

The crisis came when Cicero was a young man. In 82, the Republic’s bloodbath of a civil war, which was waged on and off for fifty years, reached its first horrific climax. Soldiers were forbidden to enter Rome, but a vengeful and ambitious general, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, led an army of Roman citizens into the city and conducted a massacre of his opponents.

The uncertainty about who was to be a victim paralyzed high society.

Eventually, a young man plucked up his courage and approached Sulla.

“We don’t ask you to exempt from punishment those you have decided to kill, but at least free from suspense those you have decided to spare,” the young man said.

“I don’t yet know whom I’m going to spare.”

“Well, then, at least make clear whom you’re going to kill.”

Sulla took the point, and saw to it that from time to time whitewashed notice boards were put up in the Forum, Rome’s central square, on which were written the names of those who were to die. There were no formal executions, and anyone who chose to was permitted to carry out killings, and qualified for a handsome reward upon the production of a severed head. A victim’s estate was forfeit. The process was called a proscription (the Latin for “notice board” is

proscriptio

).

SULLA’S OBJECT WAS

to eliminate his opponents, but his supporters often took the opportunity to settle private scores or to enrich themselves. One hapless property owner complained, “

What a disaster! I’m being hunted down by my Alban estate.”

Cicero, an ambitious lawyer in his twenties, had direct experience of this cruel and fraudulent behavior. In his first criminal case, he courageously exposed the activities of a member of Sulla’s circle, a Greek former slave named Chrysogonus. He revealed a plot to pretend that a dead landowner had been proscribed; this allowed his estate to be confiscated and sold at a knock-down price to Chrysogonus.