The Rise of Islamic State

Read The Rise of Islamic State Online

Authors: Patrick Cockburn

Patrick Cockburn

is currently a Middle East correspondent for the

Independent

and worked previously for the

Financial Times

. He has written three books on Iraq’s recent history, including

The Occupation: War and Resistance in Iraq

, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics’ Circle Awards. He has written a memoir,

The Broken Boy

, and, with his son, a book on schizophrenia,

Henry’s Demons

, which was shortlisted for a Costa Award. He won the Martha Gellhorn Prize in 2005, the James Cameron Prize in 2006, and the Orwell Prize for Journalism in 2009. He was named Foreign Commentator of the Year by the Comment Awards in 2013.

Islamic State

ISIS and the

New Sunni Revolution

Patrick Cockburn

First published under the title

The Jihadis Return

by OR Books, New York and London 2014

This updated edition published by Verso 2015

© Patrick Cockburn 2014, 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-040-1

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-049-4 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-048-7 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cockburn, Patrick, 1950–

The jihadi’s return : ISIS and the failures of the global war on terror / Patrick Cockburn.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78478-040-1 (paperback) — ISBN 978-1-78478-049-4 (U.S.) — ISBN 978-1-78478-048-7 (U.K.)

1. IS (Organization) 2. Terrorism—Middle East. 3. Terrorism—Religious aspects—Islam. 4. Middle East—History—21st century. I. Title.

HV6433.I722C64 2015

956.05’4—dc23

2014041837

Typeset in Fournier by MJ&N Gavan

Printed by in the US by Maple Press

5. The Sunni Resurgence in Iraq

6. Jihadis Hijack the Syria Uprising

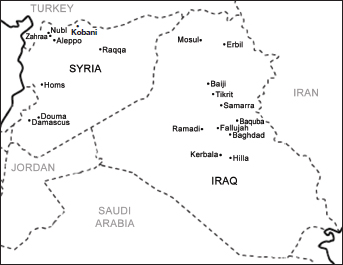

In the summer of 2014, over the course of one hundred days, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS) transformed the politics of the Middle East. Jihadi fighters combined religious fanaticism and military expertise to win spectacular and unexpected victories against Iraqi, Syrian, and Kurdish forces. ISIS came to dominate the Sunni opposition to the governments in Iraq and Syria as it spread everywhere from Iraq’s border with Iran to Iraqi Kurdistan and the outskirts of Aleppo, the largest city in Syria. During this rapid rise ISIS acted as though intoxicated by its own triumphs. It did not care about the lengthening list of its enemies, bringing together

longtime rivals like the US and Iran by a common fear of the fundamentalists. Saudi Arabia and the Sunni monarchies of the Gulf joined in US air attacks on ISIS in Syria because they felt this group posed a greater threat to their own survival and the political status quo in the Middle East than anything they had seen since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990.

Iraq and Syria moved closer to disintegration as their diverse communities—Shia, Sunni, Kurds, Alawites, and Christians—found that they were fighting for their very existence. Merciless in enforcing compliance with its own exclusive and sectarian variant of Islam, ISIS killed or forced to flee all whom it targeted as “apostates” and “polytheists” or who were simply against its rule. Its leaders were the products of a decade of war in Iraq and Syria, and deliberate martyrdom through suicide bombing was a central and effective feature of their military tactics. The world had seen nothing like their use of public violence to terrorize their opponents since the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia forty years earlier.

The crucial date was June 10, 2014, when ISIS captured Iraq’s northern capital Mosul after four days of fighting. On September 23, the US extended its use of airpower to Syria to prevent the jihadis’ expansion. During the 105 days separating these two events ISIS

rampaged through Iraq and Syria, defeating its enemies with ease even when they were more numerous and better equipped. Unsurprisingly, they attributed their victories to divine intervention.

In contrast, the Iraqi government had an army with 350,000 soldiers on which it had spent $41.6 billion in the three years since 2011. But this force melted away without significant resistance. Discarded uniforms and equipment were found strewn along the roads leading to Kurdistan and safety. Within two weeks those parts of northern and western Iraq outside Kurdish control were in the hands of ISIS. By the end of the month the new state had announced that it was establishing a caliphate reaching deep into Iraq and Syria. Its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi said it was “a state where the Arab and non-Arab, the white man and black man, the easterner and westerner are all brothers … Syria is not for the Syrians, and Iraq is not for the Iraqis. The Earth is Allah’s.”

Al-Baghdadi’s words showed an intoxication with military victory that only increased as his men outfought and defeated opponents in Syria and Iraqi Kurdistan. The ISIS threat to the Kurdish capital Erbil in August provoked US air strikes inside Iraq, which were later extended to Syria on September 23. US airpower might not have been enough to eliminate or even contain

ISIS, but its use forced the fighters to abandon semi-conventional warfare conducted by flying columns of vehicles (often American Humvees captured from the Iraqi army) that were packed with heavily armed fighters. Instead ISIS has reverted to guerrilla warfare, no longer hoping to strike a swift knockout blow against Bashar al-Assad, the Syrian Kurds, or other Syria rebel groups that it had been fighting in an inter-rebel civil war since January 2014.

Over the course of those 100 days, the political geography of Iraq changed before its people’s eyes and there were material signs of this everywhere. Baghdadis cook on propane gas because the electricity supply is so unreliable. Soon there was a chronic shortage of gas cylinders that came from Kirkuk; the road from the north had been cut by ISIS fighters. To hire a truck to come the 200 miles from the Kurdish capital Erbil to Baghdad now cost $10,000 for a single journey, compared to $500 a month earlier. There were ominous signs that Iraqis feared a future filled with violence as weapons and ammunition soared in price. The cost of a bullet for an AK-47 assault rifle quickly tripled to 3,000 Iraqi dinars, or about $2. Kalashnikovs were almost impossible to buy from arms dealers, though pistols could still be obtained at three times the price of the previous week. Suddenly,

almost everybody had guns, including even Baghdad’s paunchy, white-shirted traffic police, who began carrying submachine guns.

Many of the armed men who started appearing in the streets of Baghdad and other Shia cities were Shia militiamen, some from Asaib Ahl al-Haq, a dissident splinter group from the movement of the Shia populist nationalist cleric Muqtada al-Sadr. This organization was controlled by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and the Iranians. It was a measure of the collapse of the state security forces and the national army that the government was relying on a sectarian militia to defend the capital. Ironically, up to this moment, one of Maliki’s few achievements as prime minister had been to face down the Shia militias in 2008, but now he was encouraging them to return to the streets. Soon dead bodies were being dumped at night. They had been stripped of their ID cards but were assumed to be Sunni victims of the militia death squads. Iraq seemed to be slipping over the edge into an abyss in which sectarian massacres and countermassacres might rival those during the sectarian civil war between Sunni and Shia in 2006–7.

The hundred days of ISIS in 2014 mark the end of a distinct period in Iraqi history that began with the overthrow of Saddam Hussein by the US and British invasion

of March 2003. Since then there has been an attempt by the Iraqi opposition to oust the old regime and their foreign allies and to create a new Iraq in which the three communities shared power in Baghdad. The experiment failed disastrously, and it seems it will be impossible to resurrect that project because the battle lines among Kurd, Sunni, and Shia are now too stark and embittered. The balance of power inside Iraq is changing. So too are the de facto frontiers of the state, with an expanded and increasingly independent Kurdistan—the Kurds having opportunistically used the crisis to secure territories they have always claimed—and the Iraqi-Syrian border having ceased to exist.

ISIS are experts in fear. The videos the group produces of its fighters executing Shia soldiers and truck drivers played an important role in terrifying and demoralizing Shia soldiers at the time of the capture of Mosul and Tikrit. Again, there were grim scenes uploaded to the Internet when ISIS routed the peshmerga (Kurdish soldiers) of the Kurdistan Regional Government in August. But fear has also brought together a great range of opponents of ISIS who were previously hostile to one another. In Iraq the US and Iranians are still publicly denouncing each other, but when Iranian-controlled Shia militias attacked north from Baghdad in September to end the ISIS siege

of the Shia Turkoman town of Amerli, their advance was made possible by US air strikes on ISIS positions. When the discredited Iraqi prime minister Nouri al-Maliki was replaced by Haider al-Abadi during the same period, the change was backed by both Washington and Tehran. Maliki briefly considered resisting his displacement by mobilizing military units loyal to him in central Baghdad, but he was sharply warned against staging a coup by both Iranian and American officials.

Of course, American and Iranian spokesmen deny that there is active collaboration, but for the moment they are pursuing parallel policies towards ISIS, communicating their intentions through third parties and intelligence services. This is not exactly new: Iraqis have always said cynically that when it comes to Iraq, “the Iranians and the Americans shout at each other over the table, but shake hands under it.” Such conspiracy theories can be carried too far, but it is true that, when it comes to relations between the US and its European allies on the one side, and Iran and the Syrian government on the other, there is a larger gap today than ever before between what Washington says and what it does.

The ISIS assault on the Kurds and, in particular, the Kurdish Yazidis in early August opened a new chapter in the history of American involvement in Iraq. The swift

defeat of the peshmerga, supposedly superior fighters compared to the soldiers of the Iraqi army, was a fresh demonstration of ISIS’s military prowess. Probably the military reputation of the peshmerga had been exaggerated: they had not fought anybody, aside from each other, for a quarter of a century, and an observer who knew them well always used to refer to them as the “pêche melba,” adding that they were “only good for mountain ambushes.” Jolted by the swift ISIS successes, the US intervened to launch air strikes to protect the Kurdish capital Erbil. From then on the US was back in the war, but reluctantly, and more aware than during the invasion of 2003 of the dangerous complexities of politics and warfare in Iraq. Again and again, President Obama and US officials said they needed a reliable partner in Baghdad, a more inclusive and less sectarian government than that of Maliki, if the US was to deploy its military might. Washington’s aim was the sensible one of splitting the Sunni community off from ISIS and isolating the extremists, much as it had done during the “surge” in US troop numbers in 2007. The Americans argued that if at least part of the Iraqi Sunni community was to be conciliated, there had to be a government in Baghdad willing to share power, money, and jobs with the Sunni.

As so often in Iraq and Syria, this was easier said than done. Many of the Sunni living in the new caliphate did not like their new masters and were frightened of them. But they were even more frightened of the Iraqi army, the Shia militias, and the Kurds in Iraq, and the Syrian Army and the pro-Assad militias in Syria. The dilemma facing the Sunni in Iraq and Syria is graphically evoked in an email from a Sunni woman friend in Mosul, who has every reason to dislike ISIS, which was sent in September after her neighborhood was bombed by the Iraqi air force. It is worth quoting at length, as it shows how difficult it will be for the Iraqi Sunni to look on the government in Baghdad as anything but a hated enemy. She writes:

The bombardment was carried out by the government. The air strikes focused on wholly civilian neighborhoods. Maybe they wanted to target two ISIS bases. But neither round of bombardment found its target. One target is a house connected to a church where ISIS men live. It is next to the neighborhood generator and about 200–300 meters from our home. The bombing hurt civilians only and demolished the generator. Now we don’t have any electricity since yesterday night. I am writing from a device in my sister’s house, which is empty. The government bombardment did not hit any of the ISIS men. I have just heard from a relative who visited us to check on us after that terrible night. He says that because of

this bombardment, youngsters are joining ISIS in tens if not in hundreds because this increases hatred towards the government, which doesn’t care about us as Sunnis being killed and targeted. Government forces went to Amerli, a Shia village surrounded by tens of Sunni villages, though Amerli was never taken by ISIS. The government militias attacked the surrounding Sunni villages, killing hundreds, with help from the American air strikes.

Much the same is true of Syria. ISIS is more popular in the Sunni towns and villages they have captured around Aleppo than many other rebel groups that are halfway to being bandits. Here ISIS has been on the offensive and inflicted the most serious defeats the Syrian army has suffered in three years of war, capturing a well-defended air base at Tabqa in eastern Syria. Karen Koning AbuZayd, a member of the UN’s Commission of Inquiry in Syria, said at that time that more and more Syrian rebels were defecting to ISIS: “They see it is better, these guys are strong, these guys are winning battles, they were taking money, they can train us.”

US air strikes will inflict casualties on ISIS and make it more difficult for their columns of vehicles to move on the roads. But being the target of US planes also has advantages for them, because there will inevitably be civilian casualties. Airpower is no substitute for a

reliable ally on the ground, and may be counterproductive in terms of alienating the local population. It may kill a number of ISIS fighters—but then many went to Iraq and Syria with the express intention of becoming martyrs. In early October the shortcomings of seeking to hold back ISIS by airpower alone were evident: its fighters were still advancing against the Syrian Kurds at Kobani and against Iraqi government forces west of Baghdad.

The political weakness of the US-led coalition was also becoming evident, because prominent members like Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Turkey were as hostile to the Assad government, Syrian Kurds, and those fighting ISIS on the ground as they were to ISIS itself. US Vice President Joe Biden gave the US government’s real view of its regional and Syrian allies with undiplomatic frankness when speaking at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics on October 2. He told his audience that Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and UAE

were so determined to take down Assad and essentially have a proxy Sunni-Shia war. What did they do? They poured hundreds of millions of dollars and tens of thousands of tons of weapons into anyone who would fight against Assad, except that the people who were being supplied were al-Nusra and

al-Qaeda and the extremist elements of jihadis coming from other parts of the world.

He added that ISIS, under pressure in Iraq, had been able to rebuild its strength in Syria. As for the US policy of recruiting Syrian “moderates” to fight both ISIS and Assad, Biden said that in Syria the US had found “that there was no moderate middle because the moderate middle are made up of shopkeepers, not soldiers.” Seldom have the real forces at work in creating ISIS and the present crisis in Iraq and Syria been so accurately described.