The Red Market (12 page)

Authors: Scott Carney

A few months after that comment was posted, Shankar informed me that a DNA test was in the works. After years of pressure, the FBI collected samples and forwarded them to an Indian laboratory. From here it is a waiting game as the lab pushes through years of backlog until it eventually answers the question of Subash’s identity scientifically.

The American family, however, has yet to make contact with Nageshwar Rao and Sivagama through any of the means available—with or without my involvement—to verify the police case independently. While claiming their child has no identifiable birthmarks, they have never allowed an outside party to verify dissimilarities.

But Nageshwar Rao remains hopeful. He continues with his regular treks to an office building near the High Court, where he trades manual labor for representation by one of Chennai’s top lawyers. He climbs the concrete steps to an office in the back, passing plate glass windows where legal clerks are filing hundreds of briefs, generating piles. Buried somewhere in this sea of paperwork are the petitions he has filed on behalf of his lost son.

Striding into the bustling office, he asks the first clerk he sees whether there has been any news from America.

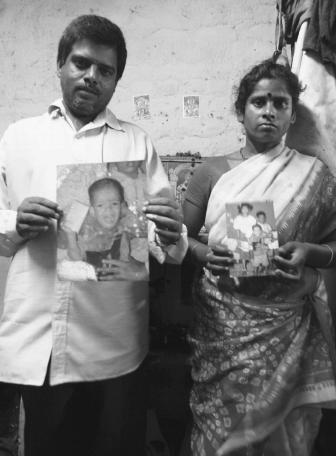

Sivagama and Nageshwar Rao hold photos of their missing son Subash, who was kidnapped off the streets of Chennai in 1999. Police say that Subash now resides with a Christian family in the American Midwest. Although I was able to make contact with the American family, they have refused to confirm their child’s identity, saying that when he reaches eighteen they will tell him that he may have been a victim of kidnapping.

Sub-zero storage containers designed to cryo-preserve human eggs. These buckets of eggs are in the basement laboratory of the Institut Marquès in Barcelona, Spain. Most people who sell their eggs in Spain are immigrants and students who earn between $800 and $1,500 for their donation.

K

RINOS TROKOUDES KNOWS

this much about women: “If you pay something,” he says, “you get lots of girls.” Trokoudes does not mean that the way you may think. He is an embryologist. His business is harvesting human eggs. The thick mat of silver hair on his head matches the white lab coat that he wears every day, and his welcoming smile instantly sets his patients at ease as much as the medical diplomas that line his walls.

In 1992 he made the

Guinness Book of World Records

for facilitating a forty-nine-year-old woman to become pregnant through in vitro fertilization (IVF). The record has been broken several times over (by 2008 a seventy-year-old Indian woman gave birth to IVF-conceived twins), but Trokoudes’ pathbreaking work helped cement his homeland of Cyprus’s reputation as a place willing to push the boundaries in the field of embryology. Since then, through the quirks of geography, regulatory neglect, and global economics, the small island nation in the middle of the Mediterranean has become a focal point in the global trade in human eggs.

In one sense, a woman’s ovaries hold the potential to bring life into the world, but they are also a gold mine of almost three million eggs just waiting to be harvested and sold to the highest bidder. Trokoudes sees it both ways. Since he started the Pedieos clinic in 1981, he has been working with a virtually unlimited supply of egg donors—mostly nonnative Cypriots who are relatively poor and find the cash they receive for donating eggs is an important supplement to their incomes. With a shrug of his shoulders he says, “Donors are available in areas where the income is low.” Cyprus, which has both the inflated costs of an island nation and a large, poorly paid immigrant population, is the perfect incubator for cash-starved donors.

A full-service egg implantation with in vitro fertilization costs between $8,000 and $14,000 in Cyprus, about 30 percent less than the next cheapest spot in the Western world. Even more important, patients rarely have to wait more than two weeks to implant donor eggs, which is a blessing for people coming in from the United Kingdom, where strict limits on who can donate eggs have made the waiting list more than two years long. This year a third of his patients flew in from abroad and he hopes to double that number in the future.

“If you have the donors,” he says, “you have everything.”

Over the past decade the global demand for human eggs has grown exponentially and without clear guidelines, proliferating in lockstep with a fertility industry that has become a multibillion-dollar behemoth. Three decades after the introduction of in vitro fertilization, some 250,000 test-tube babies are born each year. While the vast majority are still products of their biological mother’s eggs, the desire of older, sometimes postmenopausal, women to become moms has fed the rapid growth of a questionably legal market for human eggs. The business now reaches from Asia to America, from the richest areas of London and Barcelona to backwaters in Russia, Cyprus, and Latin America.

The business features well-meaning doctors alongside assembly-line charlatans, desperate parents, and unlikely entrepreneurs, all competing for one source of raw materials: women of childbearing age. It is unevenly regulated, when it is regulated at all. While every country has attempted to control the domestic market, cheap airfare and loose international guidelines make dangerous and unethical sourcing as simple as obtaining a passport. Today poor women from even poorer countries sell their eggs to entrepreneurial doctors, who then sell them to hopeful recipients from rich countries. This has given rise to a spectacular set of ethical issues: Is it really okay to treat a woman like a hen, pumping her up with steroids so that we can farm her eggs for sale? Do the standards we apply to produce ball bearings also apply to the genetic building blocks of life and the women who bear them? Is the human egg a widget and the donor nothing more than a cog?

Unfortunately, nearly the entire Western world has punted on the ethical dilemmas. Some countries, like Israel, prohibit egg harvesting on its own territories, yet still reimburse citizens for IVF, even if it’s done with donor eggs acquired in a foreign country.

US law says nothing about egg donation, although the American Society of Reproductive Medicine has nonbinding guidelines that deem any payment beyond reimbursement for lost wages and travel unethical. In Cyprus, as in the rest of the European Union, “compensation is allowed, but payment is not,” says Cypriot health ministry official Carolina Stylianou, who is responsible for regulating the island’s fertility clinics. Yes, that is as murky as it sounds.

All this mystery has helped create a vibrant marketplace with a wide range of prices and available services. In the United States, an egg implantation complete with a donor egg, lab work, and the IVF procedure itself runs upward of $40,000. The savings in Cyprus is incentive enough to bring people here from all over the world. For egg sellers (or donors, if you prefer) the price is truly all over the map. An American woman gets an average of $8,000 per batch of eggs, but can ask upward of $50,000 if she’s an Ivy League grad with an athletic build. In the United States, where the market is the most open and prospective donors post their profiles online for patients to peruse, a one-hundred-point increase in SAT scores correlates with about a $2,350 rise in egg price. On the other hand, an uneducated Ukrainian who is doped with the preparatory hormones in Kiev and then flown to Cyprus for extraction and sent home without aftercare will get only a few hundred dollars for her batch of eggs.

The businesses, run like any other global industry, take advantage of differing legal jurisdictions as well as differences in income, local ethics, and standards of living to gain a competitive edge. According to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), every year more than twenty-five thousand people in Europe travel across borders for fertility treatments. While in principle a commercial market for human eggs could function ethically, the current international system targets specific populations of vulnerable potential egg donors and effectively creates two classes of people: those who sell flesh and those who receive it.

Unlike giving blood, donating an egg is a long and painful procedure that takes a minimum two weeks of hormone stimulation and then surgical removal. Like selling a kidney, it is not something that people choose to do lightly. They take on the risk of general surgery and anesthesia, as well as complications from the hormone injections that can be painful and sometimes fatal. Even so, the procedure has been wildly popular around the world, and increasing demand for eggs far outstrips the supply of altruistic individuals who are willing to donate their eggs for free to strangers solely out of the goodness of their heart.

However, the prevailing medical ethics around egg donation deem altruistic donation the only acceptable standard. This puts regulators in an untenable position. On the one hand, authorities in Europe and the United States need a large stable of donors in order to encourage the fertility business to grow and prosper. On the other hand, they want that business to be built around an altruistic system that limits the types of incentives that might make people willing to donate their eggs.

In terms of what motivates a person to give up her eggs, there isn’t much difference between the words

compensation

and

payment

except that one translates to a lower price. Not surprisingly, these low payments only act as incentives for the poorest or most desperate people. Despite their good intentions, regulators have effectively given fertility clinics a subsidy for acquiring raw materials and allowed businesses to boom off the backs—and out of the wombs—of the poor. The relationship is almost never reciprocal.

Dr. Krinos Trokoudes, in Nicosia, Cyprus, runs a successful fertility clinic that attracts clients from abroad for egg implantation. Other clinics in Cyprus fly egg donors in from Ukraine and Russia for the express purpose of harvesting their genetic material. Egg sellers earn approximately $1,000–$1,500 for their time and trouble.

Cyprus, a recent member of the European Union, stands at the crux between taming its local market for human eggs with increased regulation that will lower supply, or liberalizing the trade and throwing open the door to payments and a large donor pool. In a way the island nation is a litmus test for the future of the flesh business. Already clinics in non–European Union countries like Russia and Ukraine are advertising their more-or-less unregulated egg business on the international market, but without the EU brand, few people want to travel there for fertility treatments. Even farther afield in countries like India, there doesn’t seem to be any problem recruiting donors with cash. Cyprus offers the perfect business platform of a Wild West egg bonanza along with a reputation for administering top-quality medicine (and white babies).

Cyprus has more fertility clinics per capita than any other country, making it one of the most highly egg-harvested locations on the planet. Whether licensed or unlicensed, they offer IVF as well as a range of fertility services, even some that are typically proscribed elsewhere, like sex selection. The fertility business here blends the shady netherworld of gray market financial transactions with commercialization of human tissue. People travel here from Israel, from Europe, from all over the world. Couples who want a child can find cut-rate help here; while poor women find a market for their eggs. Cyprus is an egg bazaar that capitalizes on both sides of the supply-and-demand equation. Internationalization has made oversight laughable.

“The most aggressive reproductive clinics are run by shady people who operate in the full sun. They laugh at the idea that the world association or one of the national associations would revoke their membership. Regulators are dogs with no teeth. County and state medical societies and boards are only interested in these issues when they smack of abortion politics. At the international level, the specter of Cyprus, of all places, taking this role is incredibly problematic. . . . Cyprus is no more prepared to be a carefully run reproductive center than South Korea was poised to do human embryonic stem cell research,” writes Glenn McGee, editor in chief of the

American Journal of Bioethics,

in an e-mail.

Cypriot surgeons like Dr. Trokoudes have been willing to push the boundaries of medicine from the moment they started their clinics. And sometimes they push too far. Consider the grandly named International IVF&PGD Centre, which has been the subject of numerous exposés and police investigations. The clinic was founded in 1996 as a go-to destination for Israelis seeking fertility treatment after paid egg donation was banned domestically. Known locally as the Petra Clinic, it can be found on a little-used coastal road between the fishing villages of Zygi and Maroni. On blustery winter days, when steady gusts of cold, salty wind barrage the dilapidated compound, it does not seem like an auspicious place to start life.

The day before, I spoke by phone with Oleg Verlinsky, son of the late owner, Yuri Verlinsky, who founded the Petra Clinic as a subsidiary of the Chicago-based Reproductive Genetics Institute. Yuri died in 2009 and the estate is still tied up in probate, but for now at least, Oleg runs the operation that also includes branches in Turkey, Russia, the Caribbean, and across the United States. In a hurried phone call he informed me that Petra is not primarily a fertility clinic—but it performs fertility-related services, including egg donation. He told me that it would be impossible for me to visit the clinic, which he said is used almost exclusively to treat rare blood disorders.