The Red Market (4 page)

Authors: Scott Carney

Instead, I hope this book offers a new way to look at markets in human bodies. By seeing the commonalities in these markets, we might come up with solutions to the problems in the tissue economy. Criminals operate in the darkest corners of our economic world. And yet they only exist because we let them. The brokers I have met have very few scruples about how they acquire human materials. They are driven by the simple capitalist axiom: Buy low and sell high. Brokers keep the supply chain away from prying eyes.

While there are often benefits to moving tissue and bodies between owners, middlemen open the door to dangerous abuses. The only way to get rid of them is to let the sun shine in and expose the entire supply chain from beginning to end. Every blood packet should be traceable to the original donor, every kidney come affixed with a name, every surrogate womb findable, and every adoption open. Each chapter tackles a different red market for human materials. Each is an exploration into the most salient, profitable, or disturbing scenarios I could find; together, they give a bird’s-eye view of red markets across the world.

At present, the power to track human materials through supply chains tentatively rests in the hands of administrative agencies. By and large, these groups are underfunded and often work hand in glove with the hospitals and brokers they are meant to oversee. International transactions often have no oversight at all. Their failures are well documented in every market I cover in this book. Instead of blindly trusting them to safely manage the process by which human bodies become transformed into commercial products, I think that the records should be open to the public.

Radical transparency ushers in a different host of problems and might even decrease the overall supply of bodies. In the United Kingdom, for example, a new initiative to open the records of egg donors has practically extinguished the supply of donor eggs for couples who are unable to conceive on their own. Now British women travel to Spain and Cyprus to buy eggs.

However, the transparency ethos destroys the opportunities for brokers who will stop at nothing to acquire human bodies. No one could be killed or kidnapped for his or her kidneys if the person who bought it was able to track down the original family to send a thank-you note. No children would be kidnapped from their parents if all adoptions were open. And no blood sellers would be locked in rooms for years at a time to create an infinitesimal increase in the local blood supply.

It’s time to stop ignoring red markets and start taking responsibility for them.

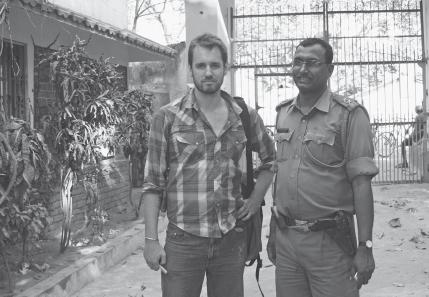

Superintendent Mishra (

right

) and Scott Carney (

left

) one year after Emily’s death. Mishra has since been promoted and drives with an escort of two jeeps packed with machine-gun-toting foot soldiers.

F

OR A BRIEF

moment Emily

4

is weightless, suspended between the point where the upward momentum from her limbs is about to give way to gravity. Here, at the apogee of her ascent, the physics have sealed her fate—but her body is still hers. In a moment the impact will set off a chain of events wherein Emily the person ceases to exist and the fate of her physical self will rest on others’ shoulders. For now though, at the crux between going up and coming down, she is immutable. Perhaps even beautiful. As she falls the wind brushing back her hair starts to gain force.

She hits the concrete, sending echoes across the monastery’s courtyard, but the handful of students who are still awake at three in the morning don’t react. Earlier that night Emily was sitting with them. She hadn’t said much, and she wandered away without fanfare. No one connected Emily’s absence to the crash in the courtyard. In India such rackets are ordinary. They didn’t investigate, so her body lies still and silent in the damp blue moonlight. The students consider themselves fortunate to meditate in the spot where the Buddha attained enlightenment in India almost three thousand years ago. The city is named Bodh Gaya in his honor; the name literally translates to “where the Buddha went.” For the last ten days they have been starved of speech and sitting in silent meditation in front of a golden Buddha statue. Strict prohibitions against talking have made them restless. Finally allowed use of their tongues again, they have stayed up late chattering like children on their last day of summer camp.

For an hour I sleep soundly just ten feet away from her body, covered by a white mosquito net and dreaming peacefully about returning home to my wife. Then someone jostles my shoulder and I open my eyes to the bearded face of one of my students, a New Yorker. He’s panicking. “Emily’s on the ground, and she’s not breathing.” Acting on instinct alone, I bolt upright and pull on a pair of blue jeans and a faded shirt and race out to the courtyard.

Stephanie, the other director in the program, is rolling the body over onto an orange camping pad. Emily’s right eye is dark and bruised and her hair is matted with blood. Too shocked to even acknowledge my presence, Stephanie is blindly focused on trying to bring Emily back to life. She does chest compressions through Emily’s red linen shirt. The contents of a medical supply bag are exploded on the dew-soaked grass with syringes and bandages strewn pell-mell. Stephanie’s lips turn up into a grimace when she sees faint traces of blood well up in Emily’s mouth with each press on her sternum. There is no pulse.

By now everyone in the monastery is on their feet and crowding the scene. A woman with long brown hair and an Austrian accent faints when she sees the blood. I dial the numbers for the program’s founders in the United States on my cell phone to deliver the news.

After I hang up I take notes and plan phone calls to her family, while three students help load Emily into a rusted ambulance that the monastery keeps to deliver medical services to villagers in the countryside. Tonight it ferries her body across parched farmland and a bustling military cantonment in the direction of the only hospital. Emily is declared dead on arrival at Gaya Medical College on March 12, 2006, at 4:26

A.M

.

By 10:26

A.M.

I’ve aged a year. The journal she left on the balcony outside her room is full of imagery that makes me suspect suicide. Ten days of silent meditation coupled with the ordinary culture shock from visiting a country half a world away from home had not sat well with her. But the reasons for her death don’t seem to matter as much as the brute force of the tasks ahead. Her home city of New Orleans is eighty-five hundred miles away; the first legs of the journey are across the parched and barren wastelands of rural India. A train accident near the rail hub in the holy city of Varanasi the night before cut the rail lines to Gaya, and the local airport seems uninterested in facilitating an airlift for a corpse.

As a red sun peeks above the horizon, two police officers in green khaki uniforms wearing semiautomatic pistols on their hips and handlebar mustaches have already seen the corpse at the hospital and have come by with questions.

“Did she have any enemies? Anyone who was jealous?” asks Superintendent Mishra, who, more than six feet tall, cuts a striking silhouette. There are two silver stars on his epaulette. He suspects murder.

“Not that I know of,” I reply, frozen by the suspicion in his voice.

“Her injuries are . . .” He pauses, uncertain of his English. “Extensive.”

I show him the spot where she had fallen, and the array of medical supplies and torn bits of emergency equipment left over from our failed attempt to resuscitate her. He writes something in a notebook but doesn’t pursue the questioning. Instead he asks me to come to the hospital. There is something he needs me to do.

Within minutes I’m sitting in the back of a police jeep with Mishra and three young guards, barely out of their teens, who are casually holding World War II–era submachine guns. The worn silver barrel of one of the Stens points toward my belly as we bump down the road. I worry that it could go off at any moment, but I don’t say anything.

Mishra turns around in the passenger seat and smiles. He seems happy to be helping an American; it’s a novelty that breaks up his ordinary police work. “How do police work in America? Is it like on TV?” he asks.

I shrug. I really don’t know.

Barreling down the opposite side of the road I see another SUV. Through the dust-matted windshield I make out the silhouette of a white woman with brown hair. It’s Stephanie. We make eye contact as the jeeps pass each other. She looks tired.

A few minutes later we reach the crowded and potholed streets of Gaya. Although it is one of the larger cities in the state of Bihar, development is a distant dream. Despite the central government’s best efforts, feudalism is still the governing policy here. The men who control the city now are the inheritors of a system that began in the times of maharajas. Giant pigs coated in black mud wander on the street sifting through trash and grunting pedestrians out of their way. Some are standing next to a butcher’s shop waiting for treats. As we zoom past, the butcher splits a skinned goat’s head in two and tosses the wasted bits to the swine. One sucks up a discarded intestine like it’s a string of spaghetti.

Three turns later the jeep breaches the compound of Gaya medical college and stops in front of a concrete building. Bright red block letters painted on the awning announce the word

CASUALTY

. In the hierarchy of Indian medical institutions this school is barely an afterthought: an aberration that only attracts the country’s most mediocre talent. Though it was established during colonial times when British bureaucrats ruled the land from beneath pith helmets and sunburns, the college today bears no vestiges of the imperial architecture. Instead, the campus is sprinkled with squat concrete buildings built on depleted government budgets. While much of India has forged ahead on an information-technology rocket ride, the state of Bihar is still sitting on the grandstands by the launching pad.

I hop out and Mishra leads me into the ward. A nurse in a Florence Nightingale–white uniform and hat greets me with dull eyes that are accustomed to tragedy. Opposite her on a concrete slab Emily’s corpse is cooling beneath a moth-eaten wool blanket. Sometime during the night the nurse brought in a few flimsy partitions to keep away the curious. Rick, an American who volunteers at the monastery’s clinic, has been waiting with her body since dark.

Mishra pulls back the shroud that has been protecting Emily from the flies and reveals her battered body. In the hours since she hit the ground the temperature of her corpse has dropped a dozen degrees and the cooling has exaggerated her injuries. A dark smear of blood stains the skin under her eye, and a bulge at the base of her neck looks like she might have broken it in the fall. Marks on her arm that were invisible when Stephanie was performing CPR are now stark and defined like military camouflage.

Mishra asks me to tell him what I see and to catalog her possessions for the police report. The police have legal custody of her body, and he’s technically responsible if anything goes missing. She’s wearing a linen shirt and a long skirt that she picked up in a Delhi tourist bazaar. There’s a string of wooden beads around her right wrist.

“What color?” he asks, again conscious of his English.

“The shirt is

lal,

red, skirt

neela,

blue,” I say. He scratches the letters onto the pad with a ballpoint pen. The injuries match her outfit.

If he is musing on the curious combination of colors, he doesn’t muse long. His thoughts are interrupted by the sounds of tires crunching on gravel, announcing a new arrival.

Outside, newsmen have pulled up in two small Maruti Omni vans. Like circus clowns they spill out into the parking lot, a jumble of bodies, sound equipment, and B-grade camcorders. The reporters’ existence, like the medical college’s, is a testament to marginalization. In the rest of the country, news channels compete for scoops, but here, reporting is a team sport. And for today’s story they share transportation, too. Sixteen people stand awkwardly around the empty vans as two producers sort gear by matching monochromatic logos on microphones to their camera counterparts.

Mishra goes out to bar their progress—or perhaps to say hello to old friends. From where I’m standing inside the ward, I can barely make out their raised voices, but I know what is coming next. I peek through the wrought-iron gate and try to catch the exact moment when a line producer palms a yellow rupee note into Superintendent Mishra’s open hand. I don’t see the exchange, but I know that I only have a few seconds to get ready for an interview.

I pull the hospital blanket back over her face and walk to the front of the room. A half dozen camera flashes momentarily blind me. A video crew blasts a hot yellow light that beats down on my forehead. The reporters churn a sea of microphones in front of my face and release their first salvo of questions.

“How did she die?”

“Was she murdered?”

“Was it suicide?”

And then, almost as an afterthought, “Who are you?”

The questions are sensible. But I don’t answer. For the last six hours my boss in the United States has been trying to get in touch with Emily’s parents, but I still don’t know if they have heard the news. There is a chance that a story could appear on an American news channel before they have been tracked down.

By now the person who Emily was has been replaced by the problem that her body represents. The urgency that was present when we were trying to save her life is over, and now all there is are the inevitabilities of death. What’s left of her is vulnerable. Perishable. And somehow a lot of people have a stake in her remains.

“No comment,” I say, squinting my eyes against the relentless glare of the camera lights. The questions keep coming, but the urgency in the reporters’ voices is fading. A gleam in one cameraman’s eye tells me that they are angling for a shot of her corpse. I raise my arm in front of his lens, but a man in a red polo shirt grabs my arm and tries to push me away. I pull against him, but it’s a lost cause. He lets go and I spin wide. Within a second they are past me and pulling back the shroud that had been covering her face.

Under the light’s harsh glare, the blood under her eye stands out dark and purple. The wound traces its way through a crack in her skull and back to her brain. On Indian television death has a starring role right next to diamond-dripping Bollywood celebrities. Tasteful shots of covered bodies and toe tags are for American newspapers. Instead, on the Indian news the faces of the dead loll obscenely, shot after grotesque shot, in unending montages of personal tragedy. India’s dead aren’t camera shy. If it is my duty to protect Emily, I have failed.

This evening, news-flash updates across the country will read:

American student dies at Bodh Gaya meditation center. Police suspect murder or suicide.

American’s don’t die in India every day. Today she will be more famous for being a dead body than for the person she was alive. For the time that it takes for one news item to transmute into another, the national attention will be on this spot. A billion people will have a chance to see her lifeless face.

I push my way back in front of the cameras but the reporters already have begun to wrap up. They have what they need.

Officer Mishra is balancing a hefty cane in his left hand. His face is a kaleidoscope of looks that say simultaneously, “Your five hundred rupees are up” and “I don’t know how these guys got past me.” Not that it matters to the reporters who have already begun to file out and get into the waiting vans. The drivers gun the engines and they race off to the meditation center to get a peek at the crime scene.