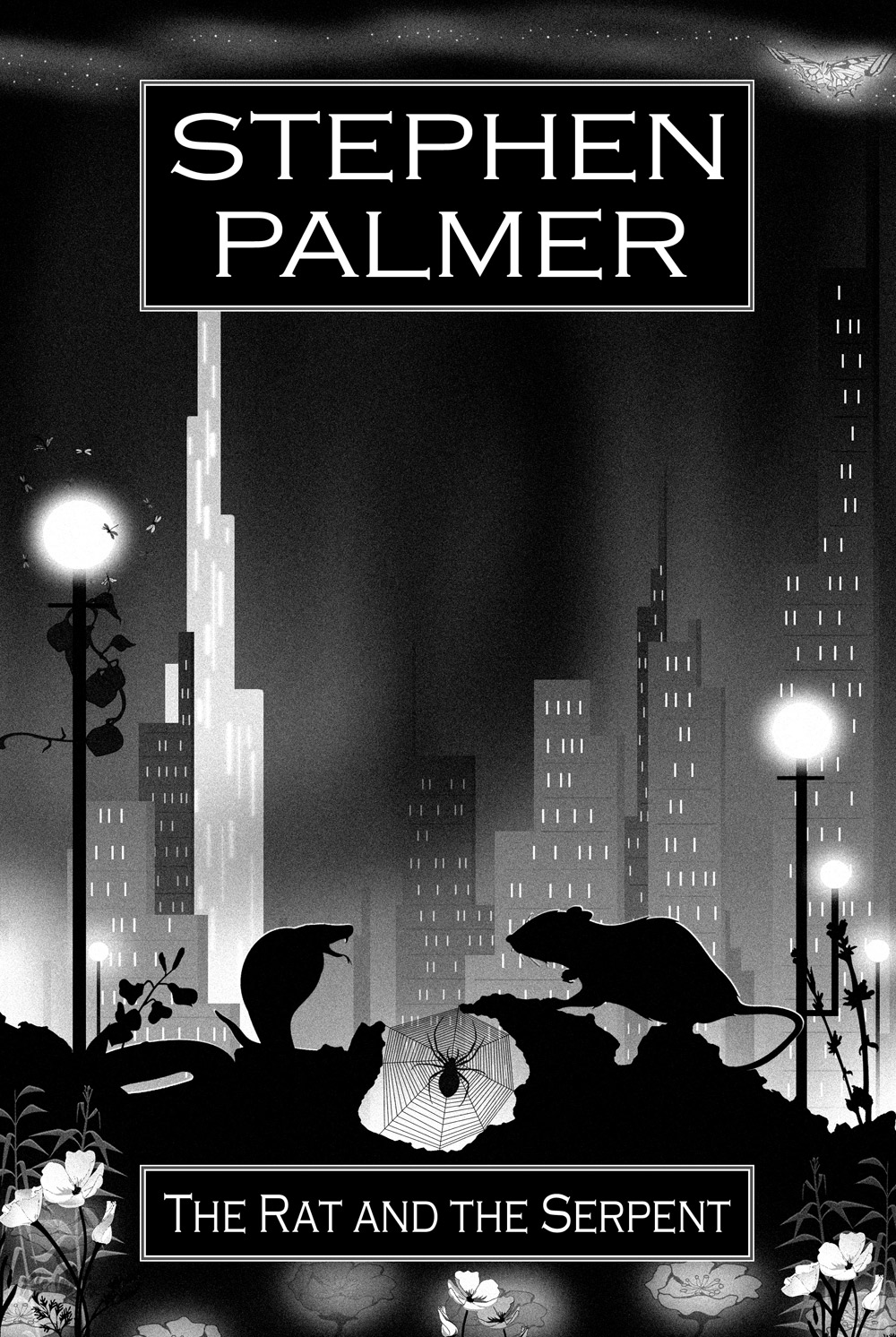

The Rat and the Serpent

Read The Rat and the Serpent Online

Authors: Stephen Palmer

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Literary, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #fantasy, #Literary Fiction

- Chapter 1

- 12.11.582

- Chapter 2

- 12.1.583

- Chapter 3

- 30.2.583

- Chapter 4

- 5.5.583

- Chapter 5

- 11.5.583

- Chapter 6

- 11.6.583

- Chapter 7

- 10.8.583

- Chapter 8

- 12.8.583

- Chapter 9

- 12.8.584

- Chapter 10

- 31.10.589

- Chapter 11

- 22.8.595

- Chapter 12

- 5.9.595

- Chapter 13

- 1.11.604

- Chapter 14

- 17.11.604

- Chapter 15

- 15.12.609

- Chapter 16

- 29.3.614

- Chapter 17

- 17.4.624

- Chapter 18

- 11.12.649

- Chapter 19

THE RAT AND THE SERPENT

a fable in black-and-white

Stephen Palmer

infinity plus

The Rat and the Serpant: a fable in black-and-white

Imagine a film made in black-and-white. Now imagine a novel written in black-and-white.

The Rat And The Serpent is a gothic tale relating the extraordinary fate of Ügliy the cripple.

Raised as a beggar in the soot-shrouded Mavrosopolis, Ügliy has to scramble for scraps of food in the gutter if he is to survive. But one day his desperation and humiliation is noticed by the mysterious Zveratu, and soon he is taking his first faltering steps into the world of the citidenizens. He meets the seductive Raknia and the arrogant Atavalens; one destined to be his lover, the other his mortal enemy. But as Ügliy ascends he becomes aware of a darkness at the heart of the city in which he lives. Slowly, he realises that the Mavrosopolis exists gloomy and forbidding around a terrible secret...

The Rat And The Serpent is a dark phantasmagoria related entirely in monochrome. Read this and enter a world portrayed as never before in the field of fantastic literature.

Published by

infinity plus

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

© Stephen Palmer 2004, 2012

Cover © Stephen Palmer

The 2004 print edition of this novel was published under the pen-name 'Bryn Llewellyn'.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Stephen Palmer to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Electronic Version by Baen Books

www.baen.com

By the same author:

Memory Seed

Glass

Flowercrash

Muezzinland

Hallucinating

Urbis Morpheos

Chapter 1

Night was at hand and it was time for me to hunt for food discarded by the citidenizenry. I stood up, my tattered parasol sending a shower of soot around me, then limped down Blackguards’ Passage to the Hippodrome. My crutch thudded against grime-encrusted paving slabs.

Between the din of the Hippodrome and the chaos of the harbour further south was a good area to search for scraps, but that fact was known to scores of other nogoths like me, each with their own territory, each nursing their hunger like an ulcer in the belly. I grimaced. Fights were commonplace. Yet, although I was crippled, I had one advantage. Despite my youth I had honed the discipline of crutch-to-hand combat into an art—and then there were the tiny spikes emerging from the foot of my crutch. So I moved forward. From the immense cellars of the Hippodrome a man had climbed up to the street, a dustbin on his back.

I knew the signs. I moved forward, focussing on the man as he emptied his bin into the gutter, but like a flock of crows a dozen other nogoths emerged from their hiding places to pounce on the food. The scraps were bruised and glutinous, but not rotten, potatoes and black olives and crusts of grey bread, and for a few seconds we all ate.

Then a shout. “Hey! You! Get away from that gutter!”

I looked up to see three men standing a stone’s throw away. Two were ordinary nogoths, but the third stood proud beside a panther on a leash, a man with limp white hair and black eyebrows, who in stature and bearing radiated a chill pride. Most of the nogoths around me scattered, leaving me and two others. We stared as the trio advanced, the food half way between the ground and our mouths. I appraised the newcomers, afraid to move, yet more afraid of losing my meal. The men wore ragged cloaks and carried parasols, but they were unkempt and showed no signs of citidenizen make-up: they were nogoths, like me, albeit of a different standing and attitude. But the panther looked thin.

The white-haired man told the other two to halt, then strode forward until he was a few yards off. “I told you to get away,” he said. “You’re still here.”

The pair at my side ran away, whimpering and scattering the potatoes that they had tried to hide in their rags. But I had not eaten for two days, and the taste of food in my mouth made me stand firm, though I knew it was unreasonable. The man stared at me and jangled the leash. “Do you see me?” he asked. “Do you know what I am?”

“I see you,” I said, glancing down to the gutter and wondering how many potatoes I could grab before I ran.

The man repeated his question in a louder voice. “Do you know what I am?”

I looked up. “Should I?” I asked.

The man was surprised, his lips drawn back to show pale teeth. “Are you a

fool?

” he asked.

I heard the fury in the man’s voice. “But—”

“I wield power. If I tell you to get away, you get away. This food is mine.”

I took a few steps backwards, knowing that the man was a shaman, his totemic animal the panther, a corporeal example of which stood silent at the end of the leash. I looked at this beast and I saw gleaming eyes, a hint of fangs beneath the soft mouth; twitching whiskers. I felt a tension in the beast as it flicked its tail from side to side.

Yet there was food here. Desperation took me. “You must leave me some,” I begged, “I’ve not eaten—”

“Quiet.”

“—I’ve eaten nothing, I swear, nothing for days. Give me a potato and a hunk of bread. A few olives. Nothing more, you can have the rest.”

The man said nothing, as if amazement at my outburst had struck him dumb. Then he jangled the leash and began to pull the handle from his wrist so that the panther could be set free.

I stood upright. “Wait,” I said. “I too am a shaman. We should not be fighting like this, we are brothers in black.”

Now the shaman’s anger turned to laughter. “You?

You,

a shaman? Look at you, like the lowest nogoth in the smallest nogoth pack, who hasn’t the wit or strength to eat—on his own admission—for days on end. You cannot treat with me. I am soon to take the citidenizen test. You are crippled dregs. You deserve to die.”

I felt anger lighting up my mind, an anger so strong it was almost pain. I found myself breathing in gasps, hoarse like a smoker. “I

am

a shaman,” I shouted. “I am a shaman and that’s the truth!”

The man took a step forward, the panther two. “Of what beast?” he asked.

I looked at the two henchmen, then at my surroundings, to see none of my scavenging kin in sight. I was alone and helpless. I turned to the man and said, “I am a shaman of the blackrat.”

The response was unexpected.

Laughter took all three of the men, the leader most of all, for while the other two tittered and scratched the stubble on their chins, the shaman leaned back, looked up at his parasol and choked out gulps of laughter, his body shaking. At length he calmed, to say, “The rat? And you think your

rat

will be a match for the panther you see before you?” He turned to his friends to add, “We’ve met a fool like no other. He may be a nogoth, but he’s missed his vocation. He should be inside the Hippodrome, not outside, yes, inside, entertaining the citidenizens with nonsensical tales.” He screeched another few laughs. “Tell me more, rat boy! Tell me how your rat will take on my panther. Describe the battle and spare me none of the details!”

All three men were now convulsed with laughter. I stood motionless, awash with fear, with despair, aware now that I had acted like a naive. The humiliation was intense. I dropped my parasol so that my face was hidden and turned to face the building opposite the Hippodrome, but there I saw other pale faces emerging from the murk, nogoths like me, some baffled, others amused.

The humiliation was complete.

The shaman jangled the chain a final time, removing the handle from his wrist and letting it fall to the street, and even I, torn between the courage of despair and the pain of starvation, knew it was time to run. So I ran as best I could, my crutch thumping against the street. The panther did not bother to catch me; it ambled. But the shaman and his friends stretched out their hands, showed their front teeth, and, skreeking like a horde of rodents, pretended to give chase, until I was back in Blackguards’ Passage and the stink of the Hippodrome was lost in soot and shadow.

I wept. I had no food and no hope of returning to find scraps. And the tale of my humiliation would leap from nogoth to nogoth, from Hippodrome packs to harbour gangs, until I was forced to make the move from poverty to utter despair, and then, like so many others before me, to final rest in my grave.

I was a nogoth. I had no future.

Life as a nogoth was meaningless, it was just existence: life by accident.

In the madness of my retaliation I had dropped my parasol. Now I stared up into the mist of soot falling so fine yet so strong from the night clouds, and I yelled, “But I

am

a shaman! I am Ügliy the blackrat shaman. Why am I here in this gutter?”

My voice faded into a hoarse retch as emotion took me. I sat and put my head in my hands.

I looked up to see a pair of rats emerging from a sewer grille. They stared at me, noses twitching. Certain they were mocking me I leaped up and ran over, kicking out in an attempt to smash them against a wall. But they were too quick, skittering away, squeaking. I wailed, aware that I had acted against my principles. In humiliation I was becoming what the white-haired man had said I was: no shaman, turning against myself, a nogoth without hope, denying my own existence because that was what others were doing. Deserving of death.

I fell to the street. Yet even that was a meaningless gesture, for there was nobody to watch me collapse, not one single person. The citidenizens of the Mavrosopolis had long since moved from wherever they slept during the day to wherever they lived at night.

So it was that my thoughts turned to these people, with their make-up and their undamaged parasols, living lives about which I knew nothing; healthy and at peace, or so I assumed. Never hungry, or so the stories ran. Suddenly I imagined myself from the perspective of a high window—a small figure, but

alive

. And I was a shaman. That made me an outsider even in nogoth society, but being a shaman meant that I had something to give to others, and something to do in life. I knew wrong when I saw it, none better, since my years had been one long struggle, with my gaze turned ever upward to the promise of better times; and I knew that wrong had to be transformed into right. More than that, I knew from some well in my heart that wrong

could

be transformed into right. Even nogoths knew a concept of hope.

I had to do something. This day must be a turning point. The three men thought I was bluffing, but I never lied. I had told the truth about my rat guides.

Again I looked up into that familiar blackness. “I must change all this,” I muttered at the sky. “There must be more to living than hunger and pain.”

A thought entered my head, borne on the scornful voice of the panther shaman:

you cannot treat with me, I am soon to take the citidenizen test.

Yes! Becoming a citidenizen was possible. Many nogoths took tests to become citidenizens of the Mavrosopolis, but I, who had all my life floundered in dark streets and passages, had no concept of such a leap, and so I had never considered it. But tonight was different. Humiliation burned in my body. Isolation was sending me mad. I had to raise myself before the grave claimed me. I had to become a citidenizen. It would bring meaning to my life, it would bring an end to tortured days.

And then a voice wound its way into my mind. “Did they offer you any food?”

A croak of a voice. I looked up to see the silhouette of a man against the lamps of distant Divan Yolu Street. I jumped to my feet. “Who are you? From the panther shaman?”

“No.”

Nothing more followed by way of an introduction. I shrank against the wall, every nogoth instinct telling me to flee, but I was transfixed as if by sorcery.

“You have nothing to fear,” said the voice.

I relaxed a little. There was a whisper, a hiss, then the flare of a lantern shining through the soot. The light revealed a tall man, old, with tufts of white hair emerging uncombed from a balding pate; a cadaverous face with black eyes from which the rheum ran. He carried a small parasol.

“Did they give you the food you asked for?” he repeated.

I shook my head. “Who are you?” I asked.

“My name is Zveratu. I am not here to harm you. Look at me—I am an old man.”

I noticed a gleam at the belt under Zveratu’s cloak. “You carry a longsword,” I remarked.

“For defence only,” came the reply.

I studied Zveratu’s pale and wrinkled skin. It was difficult to tell in the flickering light, but the old man seemed to be wearing make-up, a foundation of white, and kohl around his eyes: black surrounding a dark gaze.

I summoned up my courage to say, “You don’t look like a nogoth. You’re not one of us, why should I listen to you?”

“Because I have something to say, something that I think you are well suited to hearing. But you are in a hurry? You can run along if you want to.”

I smacked my crutch against the wall at my side. “I cannot run. Instead I hobble fast.”

“Do you wish to leave then?”

I frowned. “Are you toying with me? I’ll throw you into the Propontis.”

“You would have to lift me first.”

“I have friends who would help.”

Zveratu said nothing, but at length he remarked in a soft voice, “Are these the friends who deserted when you faced the panther shaman?”

I grimaced, glancing back down the passage. “You’re just playing with me. I bet you work for that man, just driving the knife deeper in. Well I have had enough!”

“Indeed you have, Ügliy,” said Zveratu, without any change of expression, “and that is why I sought you.”

“Then what do you want?”

“One of my many tasks is to seek nogoths suitable for the citidenizenry. I believe you to be one such. I am here to encourage you.”

I stuttered, “No, you can’t be. You’re toying with me again. Well, I can’t

stand

it.” My voice begain to wail as I said, “I’ve got to get out of here before it’s too late! I’m not ready for my grave.”

Zveratu nodded. “That is one of the tragedies of life. Nobody is ready for the grave.”

“So who are you?” I asked, the emotions churned up by desperation making my eyes water and my throat ache. “Who are you, really?”

“I think you should make a commitment to passing the test that would lead on to you becoming a citidenizen.”

“What is this test? I’ll pass it—anything!”

Zveratu raised a hand. “Enough. Any test is a month away. First you have to become visible to citidenizens and to those nogoths taking or about to take the test.”

“I am the lowest of the low.”

Zveratu approached. He put one hand to my chin, appraised my face, then said, “In a sense. But there are many other senses.”

“You speak in riddles. You must be a citidenizen. You’re wearing make-up, aren’t you?”

“What happenes to nogoths who wear make-up?” Zveratu countered.

“They vanish.”

“The citidenizenry deals with them. That is all you need to know.”

I shrugged. “So what do I do? Who do I see?”

“The time for seeing people is later. First we have to decide if you are ready for the commitment, if you are ready to make a serious promise.”

“I am ready!” I yelled.

Zveratu nodded. He looked along the passage, then glanced up at the surrounding buildings and towers. “In which direction would you say the citidenizenry lay?”

“Up,” I replied without hesitation. “It has to be up.”

Zveratu shook his head. “First we go down,” he said, pointing to the street slabs. “Follow me.”

Zveratu led me along the passage until we stood at the edge of Divan Yolu Street, which lay sparkling like opals behind a hallucinatory mist of soot. The glittering lamps of a thousand windows shone in a serpentine curve, east towards the Gulhane, west into Yeniceriler Street. In this street hundreds of parasols jostled as the citidenizens of the Mavrosopolis went about their evening business, while—hardly visible to them, though not to me—half as many nogoths lay like discarded packages in the doorways and the gutters. Many of these nogoths seemed contented, and some were chewing food. They had rich pickings. But competition for the best places was intense, and only the most cunning survived. Crippled from birth, I had no chance of winning any such competition.