The Rags of Time (18 page)

Authors: Maureen Howard

Score one for my brother.

We have closed the house, the Levittown ranch in the Berkshires, pre-Sheetrock. The garden nearing its end. A daylily protected by the fence held its final bloom tight. Lady’s mantle gone soggy. The first time we’ve done this, drained the pipes, cleared the fridge of cheese ends, onions, celery best not to mention. Bitter marmalade, ketchup transport to the city. Crackers in a tin, denied to the mice, though in the Spring we’ll find stuffing pulled out of the sofa, books chewed at the spine, candles gnawed to the wick. The few will lie dead in their tracks. The little house sits across from the town cemetery. You went for a last walk through the gravestones to the top of the hill. It’s not much of a climb.

You said:

Best not chance it.

Best not chance it.

Not even for the view stretching to yonder?

Last time I was allowed to garden, digging in the new laurel, a funeral procession drove up to the height where the old families of the town are laid to rest. The bagpipes sounded cheery, then wheezed to a dirge.

Last time I was allowed to garden, digging in the new laurel, a funeral procession drove up to the height where the old families of the town are laid to rest. The bagpipes sounded cheery, then wheezed to a dirge.

Well beyond the middle of the journey of my life, I’ll not come to a dark wood, just the loop in a clearing of memory. Back-braiding to the college girl who tossed Greek tragedies away and took Dante as her poet. I find her wonder and despair at the discovery of greed, usury, fraud unconvincing. She misplaced her faith, that’s all. Hell passed in a term, became plain-spoken outrage at corruption whatever the current scene. Soon she will find some relief in preparations for the terrarium, for the grandchildren, of course; here and now will see again the stars. Pebbles sprinkled with charcoal from the iron stove in the country, soil tamped with sphagnum moss. They will choose stones and sticks to create their landscape, form hills and ravines. Wood ferns and lichen brought down from the garden; from the florist, a bromeliad and the bird’s nest fern that delighted Columbus, all to be arranged in the giant brandy snifter, well misted with tap water. A rain forest sporting botanicals, the exotic blooms that heaven allows. The Park across the street not yet in Fall glory.

Daybook, All Saints’, November 1, 2007Your wax teeth, my fright wig, cheap goods meant to fool no one. Amusing the children who came to our door last night, that’s all we were up to. You had no patience with teenagers who grabbed the Mars Bars and Snickers, leaving the stale corn candy for little kids. Two polite girls—twelve, thirteen?—done up in tawdry silk rags, rattled their UNICEF canisters. You stuffed dollar bills through the slot of goodwill.

Gypsies?

Summer of Love. We don’t do Gypsies.

In the lobby I’ve seen these girls exchange conspiratorial glances, sniggering at El Dorado inmates. An unearned innocence in their crisp school uniforms, Academy of the Sacred Heart. Still, they alone collected for the world’s hungry children. You were left with a wad of singles.

We feared superheroes, believed in their transformation. So truly other, unlike the actor who paced in front of our building this afternoon as I was about to take off for the Park. Cell phone at ear, shouting—

Pay to play, pay to play?—

impatient with the doorman who could not conjure a taxi out of chill air. Saint or sinner, he plays himself always. To be kind, which I’m not these days, I see him as an accomplished Everyman, his face a rubbery mask, different yet always the same. An honorable tradition: Cary Grant, John Wayne. I’m disclosing our addiction to old movies. Chaplin then, his performance trumping the limits of time, conjuring laughter from pratfalls, his sly smirk of victory. Same old, same old, yet a tear trickles down my cheek when the little fellow in the bowler hat struts down the road to his next adventure. Twirling his cane, undefeated, he is incredibly brave. I’m hopeful for him always as the screen reads THE END.

Pay to play, pay to play?—

impatient with the doorman who could not conjure a taxi out of chill air. Saint or sinner, he plays himself always. To be kind, which I’m not these days, I see him as an accomplished Everyman, his face a rubbery mask, different yet always the same. An honorable tradition: Cary Grant, John Wayne. I’m disclosing our addiction to old movies. Chaplin then, his performance trumping the limits of time, conjuring laughter from pratfalls, his sly smirk of victory. Same old, same old, yet a tear trickles down my cheek when the little fellow in the bowler hat struts down the road to his next adventure. Twirling his cane, undefeated, he is incredibly brave. I’m hopeful for him always as the screen reads THE END.

When you left for the office with those singles stuffed in your wallet, I squirreled away our feeble disguises, the presumption they will come into play next year—your nerdy wax teeth with exaggerated overbite, my Raggedy Ann wig of orange wool, forgetting I still wore the retro note, my mother’s graduated pearls. Our jack-o’-lantern deliquesces on the front hall table. Old fools, not ready to cut out the fun, nor wise enough to distinguish holiday from holy day.

The first of November was once holy to me. It’s my backdrop, you know, a worn tapestry hung in a ruined castle of faith meant to keep out the cold, or simply to display the daily rituals of the church. Now faded and frayed, yet the RC calendar with its surfeit of stories can still be read. All Saints, honoring the list of miracle workers, virgin martyrs, self-flagellates, popes not on the A list, Jesuits converting the indigenous to the blessings of their Lord. All of them winners, all saints, thus the crowd scene: (Apocalypse 7:2-12) the tribes, each with their twelve thousand believers in white robes, their foreheads marked with the indelible tattoo of Salvation. A spectacle best seen in high definition, but in the days of my belief we had only the grainy black-and-white TV. Often a ghostly gray shadow drifted across the screen, a twelve-incher set in the sun parlor, that chill appendage to our little house with uncomfortable cane chairs and struggling plants. Let me put it this way, I will attempt, in defiance of the doctors’ orders, to honor the day by walking the full distance to view secular saints of my trade, the choice few in the Park who stand watch over the language they honored.

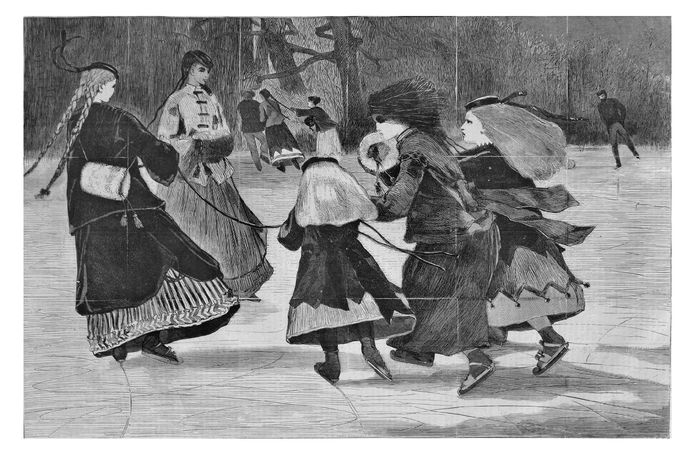

LITERARY WALKI set off on my way to Shakespeare, leader of the pack. He stands alone in his circle at Poets’ Corner, go figure. I can’t honestly say I was breathless in anticipation, just tentative as usual these days. I had lingered in my back room, writing notes toward the possible end of my days, or end of my Park project, turning through old photos of the Mall freshly planted with scrawny elms, of Ladies strolling the broad Promenade in fine shawls, girly girls chasing hoops, gents in fine equipage. I leafed through plans of

The Greensward

as submitted to the Park Commission by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, 1859, but found little satisfaction in my CP collection—the sepia photo of a single boat upon the Lake, an overexposed shot of

Mall in Its Prime,

or that tinted postcard of Bethesda Terrace sent to my mother (1910). The print on our bedroom wall—

Skaters in the Park,

Winslow Homer,

Harper’s Weekly Magazine—

no longer enchanted. I wanted to sit on a newly refurbished bench under the mighty elms that lead to the poets, not saints but they would have to do. Or simply to prove that I might, like the little tramp, go on to the next adventure.

The Greensward

as submitted to the Park Commission by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, 1859, but found little satisfaction in my CP collection—the sepia photo of a single boat upon the Lake, an overexposed shot of

Mall in Its Prime,

or that tinted postcard of Bethesda Terrace sent to my mother (1910). The print on our bedroom wall—

Skaters in the Park,

Winslow Homer,

Harper’s Weekly Magazine—

no longer enchanted. I wanted to sit on a newly refurbished bench under the mighty elms that lead to the poets, not saints but they would have to do. Or simply to prove that I might, like the little tramp, go on to the next adventure.

Well aware of the paternal note in your voice.

Take a cab.

Take a cab.

Or the bus to 59th, then walk across?

That would be cheating in the game of can-do.

That would be cheating in the game of can-do.

I stalled in my back room, looking for a note on Fitz-Greene Halleck, one of the poets portrayed beyond life size, the only one you might not know. Then again, your head is full of curiosities—orts, bits, Scrabble words, the full complement of jurists on the Warren Court, lyrics of “Red River Valley.”

Halleck, the popular poet?

Absolutely

. But the only poet with the indignity of a small sign of identification stuck in the ground. We have forgotten his newspaper versification, devalued his celebrity. The stiff cloak thrown over his chair might be that of a Roman Senator abandoned in a schoolroom play. His ink has solidified, pen hangs in midair.

. But the only poet with the indignity of a small sign of identification stuck in the ground. We have forgotten his newspaper versification, devalued his celebrity. The stiff cloak thrown over his chair might be that of a Roman Senator abandoned in a schoolroom play. His ink has solidified, pen hangs in midair.

Where’s Whitman?

Good question.

Where’s Emily?

Smoothing the folds of her lawn dress as she climbs the stairs to her virginal bedroom in Amherst. She’ll look down from the narrow window above her desk, a moody saint on a bright cloud of words.

So, a luminous Fall day, sun riding high when at last I walked directly across the street from our sandstone twin towers. I checked out the fading leaves of my favorite viburnum in the world, turned right on the Bridle Path, cut down to the grassy knoll, once Seneca Village. A woman sat on the cold ground, book clutched to her breast. Sobs choked in her throat, then spilled forth. The low pitch of her wailing.

Dismissing my inquiry and all I had to offer, crumbled Kleenex.

No, no thanks.

A tidy woman, even in her distress she smoothed a strand of pale hair off her forehead, brushed at the knees of her gray flannel slacks. Her smile apologetic, as though to admit how shameful, crying in public. She tapped the book, the cause or answer to a sad story?

No, no thanks.

A tidy woman, even in her distress she smoothed a strand of pale hair off her forehead, brushed at the knees of her gray flannel slacks. Her smile apologetic, as though to admit how shameful, crying in public. She tapped the book, the cause or answer to a sad story?

Marie Claude

,

Marie Claude!

She called as though scolding a child. Whatever tragedy started the waterworks in the Park, she turned from me in her sorrow, then caught at my sleeve, a deliberate gesture, as though to say,

Take note: I’m in control now.

Giving me the once-over. I wore the old black coat, splattered jeans. She allowed me to help her up, her mist-gray sweater the softest cashmere. I don’t often traffic with strangers in the Park, nod at a permissible distance, offer faint smiles to children. But we were not strangers. We were known to each other by caste. There, I’ve said it. We shared the downward glance of well-brought-up girls, feelings guarded, protective demeanor.

,

Marie Claude!

She called as though scolding a child. Whatever tragedy started the waterworks in the Park, she turned from me in her sorrow, then caught at my sleeve, a deliberate gesture, as though to say,

Take note: I’m in control now.

Giving me the once-over. I wore the old black coat, splattered jeans. She allowed me to help her up, her mist-gray sweater the softest cashmere. I don’t often traffic with strangers in the Park, nod at a permissible distance, offer faint smiles to children. But we were not strangers. We were known to each other by caste. There, I’ve said it. We shared the downward glance of well-brought-up girls, feelings guarded, protective demeanor.

Raw red eyes. Twirling her rings:

My husband died last night.

Then:

Four o’clock, this morning.

Steady, cultured voice delivering these few words with a hesitant smile. Was she crippled by gentility, unhinged by grief? Plain crazy?

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

slipped to the ground. Well, that’s a weeper.

My husband died last night.

Then:

Four o’clock, this morning.

Steady, cultured voice delivering these few words with a hesitant smile. Was she crippled by gentility, unhinged by grief? Plain crazy?

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

slipped to the ground. Well, that’s a weeper.

Anything I can do,

spilled from my mouth. Tears stung my eyes for no possible reason. We could not move beyond this moment of mutual pity, a recognition scene, daughter and mother long lost.

Anything,

arms open in an idle gesture. When the frame flicked forward, we were nothing to each other.

spilled from my mouth. Tears stung my eyes for no possible reason. We could not move beyond this moment of mutual pity, a recognition scene, daughter and mother long lost.

Anything,

arms open in an idle gesture. When the frame flicked forward, we were nothing to each other.

Her false smile,

It’s done, managed.

Choking sobs came upon her again.

It’s done, managed.

Choking sobs came upon her again.

She left at once, with a determined efficiency ran toward a massive outcropping of stone, an adornment hauled into view by Olmsted’s design, never a natural feature of Seneca Village. The flat land the settlers built on is a footnote in the elaborate history of the Park. I watched her lean on the mighty stone, arms outstretched as though embracing a tomb, then stomp the ground, a display of anger before she briskly headed toward the Ramble, where a weeping widow might easily lose herself in the plotted wilderness. She had left

Uncle Tom

behind. I’d come to the Park for an encounter with the poets, a look-see at Robby Burns, Walter Scott, Longfellow—recalling inappropriate lines of

Evangeline

memorized in high school.

Uncle Tom

behind. I’d come to the Park for an encounter with the poets, a look-see at Robby Burns, Walter Scott, Longfellow—recalling inappropriate lines of

Evangeline

memorized in high school.

This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks . . .

I was on my way to those gentle rhymers set

in perpetuity

on their plinths, All Saints, more or less. Did I remember each and every poet settled to his work in mighty bronze chairs, pens poised above unflappable pages? Was Longfellow among them? And why should I want to check it out now, lost clue to my scribbler’s life launched more than a half century ago with an outpouring of abysmal undergraduate poetry? To my credit, I abandoned Calliope, that carnival imp of a muse, for plain prose, which I believed to be more honest than hip-hop iambs never torn from my soul. I knew for certain that the Bard stands on his own in the Olmsted Circle, playbook in hand, contemplating his next scene:

in perpetuity

on their plinths, All Saints, more or less. Did I remember each and every poet settled to his work in mighty bronze chairs, pens poised above unflappable pages? Was Longfellow among them? And why should I want to check it out now, lost clue to my scribbler’s life launched more than a half century ago with an outpouring of abysmal undergraduate poetry? To my credit, I abandoned Calliope, that carnival imp of a muse, for plain prose, which I believed to be more honest than hip-hop iambs never torn from my soul. I knew for certain that the Bard stands on his own in the Olmsted Circle, playbook in hand, contemplating his next scene:

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shape, and gives to airy nothing

The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen

Turns them to shape, and gives to airy nothing

The following line lost in the dust mouse of memory along with CP marginalia, the year of our No Nukes march to the Sheep Meadow—’82 or ’83?; though I am clear on the Preppy Murder, Gay Pride, and the Polish Pope blessing an overflow of the faithful on the Great Lawn, urging them to multiply. I started again for the Mall when, suddenly overcome with the flip-flop thump of my heart, I turned back, took the distraught woman’s place on the cold ground. A tandem on the roadway swiveled out of control, the bikers righting themselves, not taking the spill. Mother and daughter live in our elevator bank. They pedal together in perfect trust. Always helmeted, safe home from their risky business. I have seldom seen them apart. Suddenly a moody sky. Caretakers gathering their charges. I began to leaf through Mrs. Stowe’s popular novel, could not recall when I first read it. Why would the newly minted widow bring

Uncle Tom

as a comfort to the sloping fields once Seneca Village? The blacks at this location having been turned out of their homes for the construction of the Park. As though on cue, or just coincidentally, I noticed a human bundle on a bench, awarded it my fleeting attention.

Uncle Tom

as a comfort to the sloping fields once Seneca Village? The blacks at this location having been turned out of their homes for the construction of the Park. As though on cue, or just coincidentally, I noticed a human bundle on a bench, awarded it my fleeting attention.

Other books

Daughter of the God-King by Anne Cleeland

Glory's People by Alfred Coppel

The Balloonist by MacDonald Harris

ONE WEEK 1 by Kristina Weaver

Wagon Train Sisters (Women of the West) by Shirley Kennedy

E.L. Doctorow by Welcome to Hard Times

Enemy of Mine by Brad Taylor

The 22 Letters by King, Clive; Kennedy, Richard;

The Man with the Golden Typewriter by Bloomsbury Publishing

What the Hex? (A Paranormal P.I. Mystery Book 1) by Rose Pressey