The Rags of Time (14 page)

Authors: Maureen Howard

As they prepare for descent, Jed tells all, fesses up. He’s not on his way home to the baby girl on the laptop screen. Going to visit the teenage boy he left behind. Sylvie, pert with an encouraging smile, yes, the fairy god-mother with a halo of white hair, is comfortable hearing his familiar story of ambition gone wrong, midlife crisis, the office affair. She has listened carefully to the security guards at Martha’s Institute, how one Perez son is premed, the other hijacks cars. Lola visits him in prison. Bonfilio must keep at the course in bookkeeping to get on with his life. His heart is invested in tango. Weekends he competes. Mrs. Waite has seen the head shot, hair slicked, throat gleaming with sweat in the passion of the dance. Jed has no picture of his boy left behind—a moody dropout, will not welcome this visit from his father. Below the clouds now, ordered to turn off all electronic equipment. Jed back to business. His personal story now seems impersonal. Sylvie recalls the name of the actor he resembles, a sentimental fool in old movies, eyes tearing up, the flesh wobbling on his moon face. Jed cutting her off, scribbling numbers on a scratch pad, reminds her of Gerald Waite, never her son. She feels the flight has been a waste of her seatmate’s time, not finishing his thriller, chatting up an old lady, movie out of mind before the credits run. Perhaps it will never come right, these awkward visits with his son. Gerald Waite has written himself out of his stepmother’s life, that little prince of his private school who never took to Sylvie. Each year on the Christmas card, he covets the Rhode Island highboy, though inappropriate for his high-rise in Hong Kong. Gerald is corporate, self-posted to Asia.

Martha put it simply:

Gerald needs money the way we need air

.

The whole nine yards. You know the expression?

Gerald needs money the way we need air

.

The whole nine yards. You know the expression?

I know it.

Gerald needs more than his father’s considerable salary, more than his grandfather’s take from a distinguished legal practice in the city.

Gerald needs more than his father’s considerable salary, more than his grandfather’s take from a distinguished legal practice in the city.

The little plane has nibbled to the very end of its trail on the screen. Pressure pops in her ears, and for a moment Sylvie’s hearing seems restored, that same baby crying above the pilot’s landing instructions—advice for descent, Bob called it.

Offering a stiff apology, Jed’s jowls quiver.

Sorry for the personal stuff, laying it on

.

Sorry for the personal stuff, laying it on

.

Not at all, carry-on baggage.

Returned to the strained silence of her deafness, she thinks this is what we have, perhaps it is all—the telling, telling each other our stories. In the quarter hour that remains, she sets her watch to Eastern Daylight Time, flips pages in the airline magazine that offers, for a price, comforts never imagined: a robot vacuum, an electric corkscrew and a miniature trident, the three prongs of Neptune’s weapon to spear lint. Lint?

Your clothes dryer may be clogged. Are you aware of this danger?

Now the darkening sky wavers through Sylvie’s tears. It is too foolish, this fear of fluff, yet she finds it so sad, the claims of this product offering a life free of weightless debris. She remembers he was called Cuddles, the Hungarian actor who made you laugh when you should have cried. The plane is waiting for a runway, circling the city. She sites the Triborough, Ran dall’s Island, buildings along the East River—the towers of New York Hospital, the brick of old Bellevue and in between the UN, where she worked as a young woman, a translator double-speaking the principles and arguments of international agreement. In that upended matchbox of hope, she met both her husband and her lover. She can’t remember which committee Cyril, still in uniform, reported to, but she was translating areas of dispute between French and German fisheries. She must tell Martha: the commission was called Law of the Sea.

Your clothes dryer may be clogged. Are you aware of this danger?

Now the darkening sky wavers through Sylvie’s tears. It is too foolish, this fear of fluff, yet she finds it so sad, the claims of this product offering a life free of weightless debris. She remembers he was called Cuddles, the Hungarian actor who made you laugh when you should have cried. The plane is waiting for a runway, circling the city. She sites the Triborough, Ran dall’s Island, buildings along the East River—the towers of New York Hospital, the brick of old Bellevue and in between the UN, where she worked as a young woman, a translator double-speaking the principles and arguments of international agreement. In that upended matchbox of hope, she met both her husband and her lover. She can’t remember which committee Cyril, still in uniform, reported to, but she was translating areas of dispute between French and German fisheries. She must tell Martha: the commission was called Law of the Sea.

The neighbors have turned on the porch light, left the door off the latch. The mail of the last two weeks lies in the Chinese export platter on the hall table—catalogs pushing Christmas before the first frost, Doctors Without Borders, Coalition for the Homeless and Peace Folk, as Louise calls the many organizations begging money, as well they should, given the headlines Sylvie glanced wheeling her suitcase through the airport. FAMINE, GUANTÁNAMO TORTURE. DEATH TOLL RELEASED.

She is suddenly

bone tired,

speaks the phrase aloud to the heavy silence of the house.

Now, what does that mean?

It’s the spirit that’s tired; still, she must call the neighbors who doused the plants to death, thank them for their kindness. They have turned up the thermostat, set her tea mug next to the electric kettle, propped up a card of a smiley cat—

Welcome!

Sylvie sits by the fireplace where the Waite cradle resumed its proper place. A pale patch on the floor reveals where the Connecticut clock stood for nearly two hundred years, a grandfather clock that now ticks its inaccuracies in California. Alas, the finials have been taken off to accommodate the low ceiling in Martha’s cottage. Gerald Waite, the banker still building his firm’s business in Hong Kong, is the only one who gives a damn about the antiques, in particular their value. Last Christmas card went beyond the highboy to the Pilgrim hutch and Dun-can Phyfe chairs. In a frivolous moment Sylvie sent Gerald the Canton punch bowl, never heard if it arrived back home in one piece. She’d as soon ship him every spindle and scrap, the sampler ill stitched by some long-forgotten girl, the coverlet sturdy as the day it was woven pre- Jacquard loom. Her very life is overfurnished. Alone in the house, deafness her companion, she listens to herself through worn bone. Well, there is not much flesh on her though the limbs are sturdy; didn’t she make it uphill with a spring in her step, up from the parking lot to Perez and Bonfilio, to their courtesy each day? Now she must call Louise. She gets Artie. Maisy is ill again. Each night plagued with that cough. His voice—low-pitched, solemn.

bone tired,

speaks the phrase aloud to the heavy silence of the house.

Now, what does that mean?

It’s the spirit that’s tired; still, she must call the neighbors who doused the plants to death, thank them for their kindness. They have turned up the thermostat, set her tea mug next to the electric kettle, propped up a card of a smiley cat—

Welcome!

Sylvie sits by the fireplace where the Waite cradle resumed its proper place. A pale patch on the floor reveals where the Connecticut clock stood for nearly two hundred years, a grandfather clock that now ticks its inaccuracies in California. Alas, the finials have been taken off to accommodate the low ceiling in Martha’s cottage. Gerald Waite, the banker still building his firm’s business in Hong Kong, is the only one who gives a damn about the antiques, in particular their value. Last Christmas card went beyond the highboy to the Pilgrim hutch and Dun-can Phyfe chairs. In a frivolous moment Sylvie sent Gerald the Canton punch bowl, never heard if it arrived back home in one piece. She’d as soon ship him every spindle and scrap, the sampler ill stitched by some long-forgotten girl, the coverlet sturdy as the day it was woven pre- Jacquard loom. Her very life is overfurnished. Alone in the house, deafness her companion, she listens to herself through worn bone. Well, there is not much flesh on her though the limbs are sturdy; didn’t she make it uphill with a spring in her step, up from the parking lot to Perez and Bonfilio, to their courtesy each day? Now she must call Louise. She gets Artie. Maisy is ill again. Each night plagued with that cough. His voice—low-pitched, solemn.

Sylvie in a whisper:

Tomorrow I will drive into the city. I should never have gone away.

Tomorrow I will drive into the city. I should never have gone away.

She prepares a tray of white toast and tea. For the first time, the stairs are not easy. She sets the tray on the lowboy next to the pencil-post bed. Oh, it has a verified date, this uncomfortable bed where she slept beside her late husband and with her lover, Cyril O’Connor. The call to Martha’s A-drive is not forgotten.

I’m in the lab,

Martha says,

making up for lost time.

She does not say time lost with Sylvie’s visit, their weekend jaunts up to the mission in Santa Barbara, down to the Baja Peninsula. Martha is working on a pet project, classifying sea cucumbers that thrive in a frigid canyon deep down in the sea.

Martha says,

making up for lost time.

She does not say time lost with Sylvie’s visit, their weekend jaunts up to the mission in Santa Barbara, down to the Baja Peninsula. Martha is working on a pet project, classifying sea cucumbers that thrive in a frigid canyon deep down in the sea.

Sylvie says,

Well, it’s cold here, too. The leaves are turning.

Well, it’s cold here, too. The leaves are turning.

Remember?

Martha asks.

Home again, home again, jiggity jig.

Martha asks.

Home again, home again, jiggity jig.

The last line of a ditty she chanted to the Waite children when they came from the beach in wet bathing suits, sand in their shoes. They were beyond such nursery jingles, but what did she know?

Yes, she remembers.

Home again, home again, all in a day.

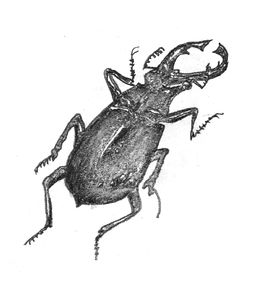

BUG BOXHome again, home again, all in a day.

And so Gregor did not leave the floor, for he feared that his father might take as a piece of peculiar wickedness any excursion of his over the walls or the ceiling.

—Franz Kafka,

The Metamorphosis

The Metamorphosis

On Riverside Drive the wind whips up from the Hudson. Artie takes his son’s hand.

First real Fall day!

First real Fall day!

His exuberant words blow away. The boy looks puzzled. Dad walking on air? They are both on their way to school: that’s Cyril’s delight. His father will leave him off, go on to his classroom, where he writes numbers and squirrelly letters on the blackboard. His father has homework most nights. Sometimes Cyril pretends he has homework. Last night he wrote his name on his backpack, wrote it all out—Cyril Moffett Freeman, a name like no other kid at his school. Cyril is the name he comes by from the grandfather who is dead. His father had no father. He was not supposed to know that. When he asked, his mother said,

You’re ours.

Well, of course. What did that have to do with the man who disappeared off the face of the earth? Moffett was in there because his mother must not leave out her parents in Wisconsin. They lived on a farm he visited every year of his life. That grandfather had almost no hair and a loud voice like a man his parents watched every night on the news. Too loud when he came to New York, showed a movie at school telling about the rows and rows of cows hooked up to his milking machines. A calf sucked milk from its mother’s udder.

Direct Delivery,

his grandfather said, laughing in case you didn’t get it. Milk was pumped into a big steel tanker to travel to the next machine, boil it up and ship it to market. He knew more than anyone in his class about pasteurizing when Grandfather Moffett ladled milk from a can for every teacher and student. The farm was cleaner than anything in New York City, so Grandpa said. He taught dairy. That was just weeks ago when Professor Moffett passed out ice cream cups for the whole lower school. For some days Cyril was made much of, then taunted by older kids—

Cyril 2%, Fat Free.

Well, he was skinny, and besides, his teacher, after a conference with his mother, advanced him to reading and math with the second grade. It was still early in the school year, and one day he broke from his class line after recess, to watch a chess game, to advise a third-grader how a pawn could block a bishop. Before he fully understood the kid’s mockery, much mooing was what he put up with. Now the best part of the day was walking hand in hand with his father.

You’re ours.

Well, of course. What did that have to do with the man who disappeared off the face of the earth? Moffett was in there because his mother must not leave out her parents in Wisconsin. They lived on a farm he visited every year of his life. That grandfather had almost no hair and a loud voice like a man his parents watched every night on the news. Too loud when he came to New York, showed a movie at school telling about the rows and rows of cows hooked up to his milking machines. A calf sucked milk from its mother’s udder.

Direct Delivery,

his grandfather said, laughing in case you didn’t get it. Milk was pumped into a big steel tanker to travel to the next machine, boil it up and ship it to market. He knew more than anyone in his class about pasteurizing when Grandfather Moffett ladled milk from a can for every teacher and student. The farm was cleaner than anything in New York City, so Grandpa said. He taught dairy. That was just weeks ago when Professor Moffett passed out ice cream cups for the whole lower school. For some days Cyril was made much of, then taunted by older kids—

Cyril 2%, Fat Free.

Well, he was skinny, and besides, his teacher, after a conference with his mother, advanced him to reading and math with the second grade. It was still early in the school year, and one day he broke from his class line after recess, to watch a chess game, to advise a third-grader how a pawn could block a bishop. Before he fully understood the kid’s mockery, much mooing was what he put up with. Now the best part of the day was walking hand in hand with his father.

There’s a kid wearing a black mask on the steps leading up to school, sweater tied round his neck for a cape. Captain Marvel, looks like maybe he’s got a sore throat. Now that his father sees the black mask, he goes on about the calendar, how we should respect it, not let the merchants take over. By merchants he means all the shops on Broadway with plastic pumpkins and ghosts in the windows, and all the creepy ads on TV.

A full week till Halloween. Why blow it before the real day?

Five nights,

Cyril corrects his father. It will be night when he goes out to spook the world. He is going to be a beetle, in fact. Today he has a ladybug in with his snack and a note to the teacher. The note says that they, the Moffett-Freemans, may be moving away within the school year, so save all records as to his progress to be transferred. Cyril had tipped a beetle into his bug box when they were in Connecticut looking at property. It was already dead on the doorsill of a dusty house where someone had died (not supposed to know that), just tipped it with a touch of his pinkie into the plastic box, which has a magnifying glass set into the lid so the bug looks larger than life, a monster black beetle with sharp horns. The hard wing case is unbroken. Too bad he never saw it fly and might not see a live one now that there’s frost, his mother says, but when they visited Sylvie in her old house, she showed him a chair which had been eaten by beetles, little holes in the wood.

Cyril corrects his father. It will be night when he goes out to spook the world. He is going to be a beetle, in fact. Today he has a ladybug in with his snack and a note to the teacher. The note says that they, the Moffett-Freemans, may be moving away within the school year, so save all records as to his progress to be transferred. Cyril had tipped a beetle into his bug box when they were in Connecticut looking at property. It was already dead on the doorsill of a dusty house where someone had died (not supposed to know that), just tipped it with a touch of his pinkie into the plastic box, which has a magnifying glass set into the lid so the bug looks larger than life, a monster black beetle with sharp horns. The hard wing case is unbroken. Too bad he never saw it fly and might not see a live one now that there’s frost, his mother says, but when they visited Sylvie in her old house, she showed him a chair which had been eaten by beetles, little holes in the wood.

Tells you how very old,

she said.

Please, not to sit in that chair.

she said.

Please, not to sit in that chair.

Which made sense, because the beetles could still be in there chomp ing. He plans to be the black beetle in his box. His mother must make horns out of cardboard, but he has not figured the carapace, how it must cover his wings, how he can scare the kids at school and still carry a bug looking bucket, a nest or hive for the treats the merchants sell.

He’s Artie to his students, often theatrical, over the top today. They have finished the problem in linear algebra according to plan, but he does not plod on with the syllabus.

Today

your teacher will turn back the clocks.

Turn to his antic self, more likely, to Freeman who got kicked out of Yale for posting answers to the difficult calculus exam on primitive e-mail.

Because it is the process,

he wrote back then,

not the answer. The rush is working it out.

No longer a smart-ass, just wanting to say to these engineering, business majors, tech-masters-to-be, that they must take care with time. In a short time, the up-and-coming time of this November, Congress has decreed that they will walk to class in the dark. They will play, let’s say Frisbee, an educated guess, in daylight saved for that purpose. He hops to the blackboard, the old miscreant Artie, to begin his lecture that has nothing to do with the job market, the one which is suddenly less healthy, the market he’s in, though how could they guess from this acrobatic instruction that leaps from Daylight Saving Time back to long shadows cast at Stone henge to the Aztec calendar and the Julian, to leap year and the missing half minute of time, to Mark Twain who marked time in a paddleboat on the Mississippi? When he doles out Heisenberg, he gets a groan from the sharpest girl, the loveliest, who never lets him walk her home when she baby-sits the kids:

We cannot know, as a matter of principle, the present in all its details

.

I’m down the rabbit hole late, late for a very important date, stop-watch and all. I come to rest, ladies and gentlemen, at the commercial countdown to Halloween, to the politics of time, the principle being that we have one more hour of sunlight to stop at the mall, so Congress has decreed. Meanwhile the alarm clock, do we use them anymore? But time being personal, I will hold you no longer. There’s a war on. It is evening in Baghdad. As a matter of principle, we wait in the dark for the morning news.

your teacher will turn back the clocks.

Turn to his antic self, more likely, to Freeman who got kicked out of Yale for posting answers to the difficult calculus exam on primitive e-mail.

Because it is the process,

he wrote back then,

not the answer. The rush is working it out.

No longer a smart-ass, just wanting to say to these engineering, business majors, tech-masters-to-be, that they must take care with time. In a short time, the up-and-coming time of this November, Congress has decreed that they will walk to class in the dark. They will play, let’s say Frisbee, an educated guess, in daylight saved for that purpose. He hops to the blackboard, the old miscreant Artie, to begin his lecture that has nothing to do with the job market, the one which is suddenly less healthy, the market he’s in, though how could they guess from this acrobatic instruction that leaps from Daylight Saving Time back to long shadows cast at Stone henge to the Aztec calendar and the Julian, to leap year and the missing half minute of time, to Mark Twain who marked time in a paddleboat on the Mississippi? When he doles out Heisenberg, he gets a groan from the sharpest girl, the loveliest, who never lets him walk her home when she baby-sits the kids:

We cannot know, as a matter of principle, the present in all its details

.

I’m down the rabbit hole late, late for a very important date, stop-watch and all. I come to rest, ladies and gentlemen, at the commercial countdown to Halloween, to the politics of time, the principle being that we have one more hour of sunlight to stop at the mall, so Congress has decreed. Meanwhile the alarm clock, do we use them anymore? But time being personal, I will hold you no longer. There’s a war on. It is evening in Baghdad. As a matter of principle, we wait in the dark for the morning news.

Other books

Their Fractured Light: A Starbound Novel by Amie Kaufman, Meagan Spooner

The Chariots Slave by Lynn, R.

You Play the Black & the Red Comes Up Up by Richard Hallas

Don't Tell Me You Love Me (Destiny Bay Romances~The Ranchers Book 6) by Conrad, Helen

The Shaft by David J. Schow

Dr. Futurity (1960) by Philip K Dick

Second Chance by Jerry B. Jenkins, Tim LaHaye

The Everlasting Covenant by Robyn Carr

Murder by Artifact (Five Star Mystery Series) by Graham, Barbara

Death Rides the Surf by Nora charles