The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain (25 page)

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

During the Younger Dryas freeze-up between 13,000 and 11,500 years ago,

31

although the polar caps started to re-form, the whole northern rim of the Scandinavian coastline was free of ice. This thin coastal strip was, however, uninhabitable polar desert, jammed up against the still massive Fenno-Scandian ice sheet (

Figure 4.2

).

32

All that changed after the end of the YD, 11,500 years ago. The ice sheets began to retreat dramatically, though a lot remained on the hills and in the high Norwegian

cordillera. The last major deglaciation did not take place until around 8,000 years ago.

33

But before this time, during the Mesolithic, the Scandinavian lowlands, including the coastal strip of Norway facing Britain, had become more habitable and much less densely forested than the rest of Europe, as also were modern-day Lapland, most of Eastern Europe and Russia.

34

The archaeological record tells us that the period after the YD saw two pioneering cultural movements moving like pincers into the Scandinavian Peninsula from south and north (compare with genetic map in

Figure 4.9

). The first of these, known as the Mesolithic Komsa and Fosna-Hensbacka cultures,

35

appeared as early as 8,600 years ago,

36

and most likely derived from the Ahrensburgian culture farther south in northern Germany and Denmark. These cultures collectively extended northwards through Scandinavia, and as far east as Finland and the Kola Peninsula. It has also been suggested that they might have been the ancestors of some of the present day Saami.

37

The second of the two Mesolithic pincer movements into the Scandinavian Peninsula came from the north-east, with carriers of cultures known as post-Swiderian, via Russian Karelia and Finland. These two Mesolithic cultural movements met up in Norway in the Scandinavian Early Neolithic, 6,500–6,000 years ago.

38

Is there other support for this archaeological perspective on the actual origins of Norwegians and Saami? Perhaps the genetic record contains analogues for the two pincer movements. For instance, could some gene lines from the south-west European

ice age refuge have arrived in the far north during the Mesolithic, or even during the Neolithic? The former seems most likely. Scandinavia and Lapland still hold a significant proportion of gene lines derived from the Franco-Spanish refuge in the south-west,

39

with the same general mix as in the British Isles but with less diversity and a relatively higher proportion of the main founding types.

40

At present, about 60,000 Saami live in the northern regions of Norway, Sweden and Finland, as well as in the Russian Kola Peninsula.

41

Because of the ice cap, these pioneers from the south-western refuge simply could not have come here before or during the YD, and so must have arrived as founders either during the Mesolithic or the Neolithic. The Saami, traditionally semi-nomadic reindeer herders, effectively still preserve elements of a Mesolithic lifestyle in parts of Lapland, while the Norwegians, for their ‘Mesolithic part’, are one of the world’s most skilled fishing nations.

If we start by examining the mtDNA evidence, we find that Norwegians have a high combined overall frequency (50%) of the two most common West European, post-LGM mtDNA founding lines H1 and H3 (for Helina’s daughters H1 and H3 in the British Isles). H1 dates to between 16,000 and 14,000 years ago in Western Europe as a whole, but, as mentioned, H1 clearly could not have arrived in Norway before the Younger Dryas, because of the ice. The unusually high frequency of H1 in Norway is likely to be an Early Mesolithic founder effect in western Scandinavia (shown in a recent re-analysis),

42

via the Danish landbridge. There is no evidence of any subsequent Neolithic spread of H1 into Norway from Spain.

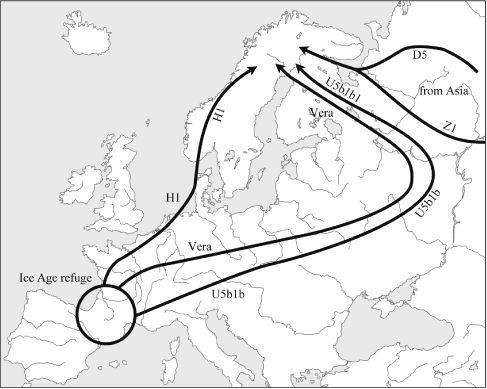

Figure 4.9a

Material gene lines in Lapland and Scandinavia derive predominantly from Iberia via both the east and west routes.

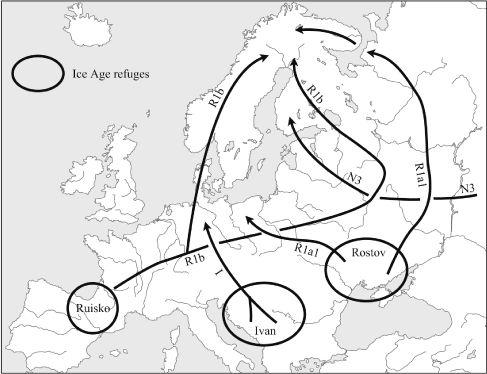

Figure 4.9b

Material gene lines in Lapland and Scandinavia derive predominantly from the Balkans (Ian) and Eastern Europe (Rostov and N3) rather than Iberia

4.9a–b

Pincer colonization of Scandinavia. Lapland and Scandinavia received two colonizations during the Mesolithic, one via Finland and Archangel, the other via Denmark. The western component derived from Iberia; the eastern pincer came both from Iberia and from farther east in Europe. This mix makes it possible to distinguish Norwegian and Danish inputs to the British Isles. Norway received over 70% of its male lines via Lapland, while Denmark received most via northern Germany.

H1 is found only in Norwegian Saami, not in more eastern Saami groups. This again suggests that the respective northern Mesolithic pincer founding events in Norway and Lapland may have been discrete and separate. H3, although not over-represented in Norway, has a similar frequency there (5.6%) to that found in the UK (4.3%). H3 is aged between 11,000 and 9,000 years in Western Europe.

43

The fact that H3 has a younger West European age than H1 in general suggests that the former moved north after the YD during the Mesolithic, rather than before.

44

The Saami also show a clear founder event for another post-LGM maternal founding line, the previously mentioned Vera (V), which clearly arose in the south-western refuge, 16,300 years ago.

45

Like H1 and H3, Vera could have arrived in northern Scandinavia only after the YD, in other words during the Mesolithic or Neolithic. Vera reaches frequencies in the Saami of anywhere up to 70% of the population (

Figure 3.4

).

46

Because of the evidence for extreme genetic drift among the Saami, it is difficult to estimate the age of Vera directly there. If Vera did not reach the Arctic Circle at the same time as elsewhere in Western Europe, we have to ask when she did get there and by which route.

These timing and route questions in Scandinavian colonization were recently investigated more fully by Estonian geneticist Kristiina Tambets and colleagues (

Figure 4.9

).

47

Tambets looked in detail at the distribution of V, H1 and other founding lines of northern Scandinavia. While concluding that H1 had moved into Norway directly via a landbridge which is now partly represented by Denmark, they argue that Vera had more likely moved through north-east Europe, through Eastern Europe, round the eastern side of the Baltic, to Lapland in the Arctic Circle, thus making an eastern pincer arm (

Figure 4.9a

). If Vera did move in via such an eastern loop, it may be possible to estimate when this happened, since Italian geneticist Antonio Torroni, who has pioneered studies of maternal post-glacial re-expansions, dated Vera to the Mesolithic at around 8,500 years ago in Eastern Europe.

48

To parallel this estimate, the oldest archaeological evidence of settlement in Finland dates back approximately 9,000 years.

49

Perhaps the simplest answer to whether Vera came into Lapland as a Neolithic or as an earlier Mesolithic intrusion lies with the surviving traditional Saami culture, which is non-agricultural and is indeed the only such surviving example in Europe. While it is likely that the Saami did receive some cultural input from farther east in Europe, for instance their language, it would be illogical to infer that, as settling agriculturalists they should then have changed their farming lifestyle

back

to being Mesolithic nomads. There are no convincing examples of this kind of cultural devolution happening elsewhere.

50

The Saami also show further genetic proofs of their ultimate origin in south-west Europe – an uncommon gene group called U5b1b accounts for the other main part of their maternal lines,

apart from Vera, and again indicates a very strong founding effect.

51

The U5b1b group has been dated to 9,000 years old, in the Mesolithic. U5b1b has also been shown to have had a strong founder effect on the Berbers of North Africa, confirming that Northern Europe was repopulated from the Franco-Spanish refuge.

52

To complete the picture for the Saami (though it has had no relevance to the British population), a later and smaller (3%) gene flow of Asian super-group M (Manju) has been suggested to have come from the East.

53

The picture for the Saami Y chromosomes also supports this pincer mix, but shows the opposite balance of eastern and western founders and adds further tantalizing detail. While the Saami maternal picture is overwhelmingly West European, the expected Y representative of Basque refuge lines, Ruisko, is not common, reaching only 9% among the Saami of the Kola Peninsula, 6% among Swedish Saami and less than 2% among Finnish Saami. Instead, his East European sibling Rostov (R1a1), common throughout Central and Eastern Europe and Siberia, and accounting for 54% of males in the refuge zone of the Ukraine, represents the Ruslan group better than Ruisko among the Saami, at rates of up to 22%.

54

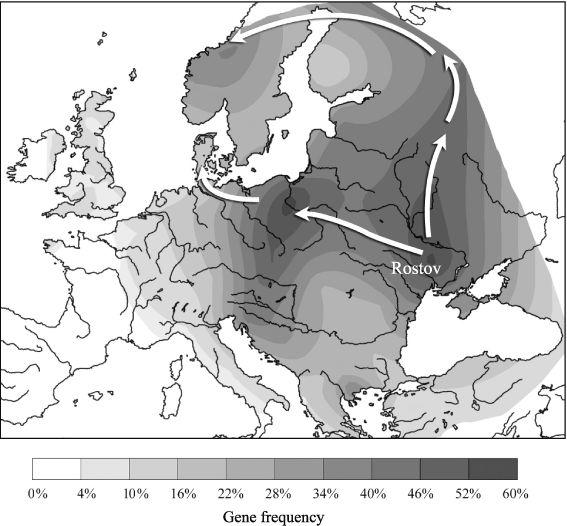

As I have mentioned, Rostov is definitely not derived from the western refuge, being absent there, but is very common elsewhere throughout Central and Eastern Europe and in Siberia. Rostov is very common in the Ukraine, suggesting that region as his Ice Age refuge. This gives us two specific male refuge markers: an eastern Rostov (

Figure 4.10

) and a western Ruisko (

Figure 3.6a

). Their ages, based on European diversity, are each consistent with an expansion from Ice Age refuges, although Rostov and the ancestral Ruslan (R1) are both ultimately much older in Asia, probably arising in India during the Early Upper Palaeolithic.

Figure 4.10

The men from the Ukrainian refuge. Rostov (R1a1) is the commonest male gene group in Eastern Europe and has three foci of highest frequency: Ukraine, Poland and Norway. Rostov most likely dispersed from the Ukrainian glacial refuge via the routes shown by arrows – as based on the gene tree and geography. Poland could have been colonized by Rostov soon after the LGM, but Norway not until the Late Mesolithic. Britain received Rostov from the Neolithic onwards.