The Origins of AIDS (10 page)

Read The Origins of AIDS Online

Authors: Pepin

Figure 5

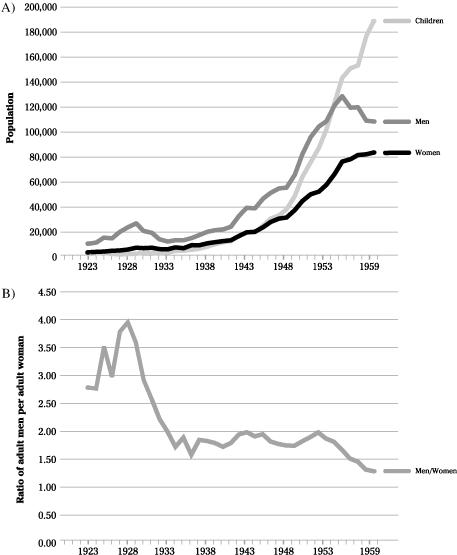

Léopoldville’s population, 1923–59: (a) adult men, adult women and children; (b) ratio of adult men to adult women.

Léopoldville’s population, 1923–59: (a) adult men, adult women and children; (b) ratio of adult men to adult women.

The economic depression of the early 1930s reverberated in central Africa, as the price of minerals and agricultural products fell dramatically. Some large companies sent back to the old continent three-quarters of their European employees and more or less the same happened to African workers. The Belgian administration preferred to return thousands of jobless men, especially the unmarried, to rural areas where they would be

less likely to defy the colonial order. By 1934, the number of women had remained stable while the number of adult men had dwindled by half. Following the economic recovery and increased production during WWII, Léopoldville had 38,940 adult men, 20,234 adult women and 19,967 children in 1944. But Léo was not yet the melting pot it later became: three-quarters of its population belonged to the Bakongo cluster of ethnic groups, from the region downriver or from the northern part of

Angola, while only 5% came from the eastern half of the colony

.

36

,

41

–

43

less likely to defy the colonial order. By 1934, the number of women had remained stable while the number of adult men had dwindled by half. Following the economic recovery and increased production during WWII, Léopoldville had 38,940 adult men, 20,234 adult women and 19,967 children in 1944. But Léo was not yet the melting pot it later became: three-quarters of its population belonged to the Bakongo cluster of ethnic groups, from the region downriver or from the northern part of

Angola, while only 5% came from the eastern half of the colony

.

36

,

41

–

43

Figure 5

shows the evolution of the male/female ratio among adults in Léo. In 1928–9, there were 3.9 men for each woman, which was a substantial improvement since in 1910 there were 10 men for each woman. The gender ratio decreased to 2.0 in 1933 and fluctuated just below 2.0 until independence. In 1942, for the very first time there was at least one child per woman on average. The flow of migrations was such that in 1946 only 11% of Léo’s inhabitants had been born in the city. In 1956, this proportion had augmented to 26%.

44

–

46

shows the evolution of the male/female ratio among adults in Léo. In 1928–9, there were 3.9 men for each woman, which was a substantial improvement since in 1910 there were 10 men for each woman. The gender ratio decreased to 2.0 in 1933 and fluctuated just below 2.0 until independence. In 1942, for the very first time there was at least one child per woman on average. The flow of migrations was such that in 1946 only 11% of Léo’s inhabitants had been born in the city. In 1956, this proportion had augmented to 26%.

44

–

46

In Brazzaville, the government also reduced its workforce during the 1930s but many were simply transferred to Pointe-Noire where opportunities were plentiful with the construction of the port. In the AEF capital, the male/female ratio was 1.9 in 1950, similar to that of Léo, but it decreased to 1.4 in 1955, as the colonial authorities were more tolerant of female migrations, even for unmarried women. Elsewhere, the male/female ratio in 1952 was 1.25 in

Bangui, 1.4 in

Libreville and

Port-Gentil, and 1.7 in Pointe-Noire

.

34

,

47

,

48

Bangui, 1.4 in

Libreville and

Port-Gentil, and 1.7 in Pointe-Noire

.

34

,

47

,

48

During WWII, the Belgian Congo made an extraordinary contribution to the war effort, to a large extent through coercive measures, especially after the Japanese conquest of parts of Asia crippled the Allies’ supply of rubber and tin. More wild rubber was gathered than during the EIC era, and the Congolese were forced to work for the colony 120 days per year. The production of copper, tin, zinc and manganese more than doubled, while that of uranium increased ten-fold, all for export to the US and Britain. This would eventually allow Belgium to emerge from the conflict debt-free, unlike the other victors.

49

,

50

49

,

50

Cut off from Europe, the colony needed to produce locally goods which until then had been imported. This generated an economic boom and the development of light industries. These processes accelerated the peopling of Léo, whose population doubled from 47,000 in 1940 to 96,000 in 1945, and doubled again to 191,000 in 1950. The exodus of

men towards the urban areas, where they enjoyed a relative freedom, was also driven by the compulsory crops imposed on rural populations. Most of the Belgian war effort was actually borne out by poor and rural African women. Many

migrants intended to stay in Léo only temporarily, but eventually settled permanently as life in the villages now seemed dull and monotonous. The intense promiscuity that resulted was seen by the missionaries as having a deleterious impact on traditional moral values. Small houses built for four persons would hold twelve people on average. The strict separation between men and women vanished.

45

,

51

,

52

men towards the urban areas, where they enjoyed a relative freedom, was also driven by the compulsory crops imposed on rural populations. Most of the Belgian war effort was actually borne out by poor and rural African women. Many

migrants intended to stay in Léo only temporarily, but eventually settled permanently as life in the villages now seemed dull and monotonous. The intense promiscuity that resulted was seen by the missionaries as having a deleterious impact on traditional moral values. Small houses built for four persons would hold twelve people on average. The strict separation between men and women vanished.

45

,

51

,

52

Meanwhile, the AEF under Félix

Éboué, the black governor from

Guyana, grandson of a slave, rallied de Gaulle’s France Libre in 1940, and the population of Brazza swelled from 22,000 to 33,500

. To affirm its independence symbolically from Britain and the US, de Gaulle made Brazzaville the capital of France Libre for two years. More than 85% of

Free French soldiers that crossed the

Sahara under general

Leclerc to attack Italian positions in

Libya were Africans from the AEF. The neglected Cinderella colony helped save the honour of France, creating a moral debt.

At the Brazzaville 1944 conference, de Gaulle promised Africans more civil rights. The numerous post-war French governments had no choice but to respect this commitment, and forced labour was abolished in 1946. Major investments were made to develop the infrastructure of Brazzaville, including a new airport, modernisation of its river port, hydro-electricity, a water treatment plant, a stadium, large administrative buildings, etc

. But as in the Belgian Congo, there was a bottleneck in the educational system. In 1952–3, there were only 1,895 secondary school students in AEF, compared to 122,951 in primary schools. The French government started giving scholarships to a small number of Africans, who were sent to France to complete secondary school and go on to university. When these countries became independent, they could at least count on a small intellectual elite

.

48

,

53

Éboué, the black governor from

Guyana, grandson of a slave, rallied de Gaulle’s France Libre in 1940, and the population of Brazza swelled from 22,000 to 33,500

. To affirm its independence symbolically from Britain and the US, de Gaulle made Brazzaville the capital of France Libre for two years. More than 85% of

Free French soldiers that crossed the

Sahara under general

Leclerc to attack Italian positions in

Libya were Africans from the AEF. The neglected Cinderella colony helped save the honour of France, creating a moral debt.

At the Brazzaville 1944 conference, de Gaulle promised Africans more civil rights. The numerous post-war French governments had no choice but to respect this commitment, and forced labour was abolished in 1946. Major investments were made to develop the infrastructure of Brazzaville, including a new airport, modernisation of its river port, hydro-electricity, a water treatment plant, a stadium, large administrative buildings, etc

. But as in the Belgian Congo, there was a bottleneck in the educational system. In 1952–3, there were only 1,895 secondary school students in AEF, compared to 122,951 in primary schools. The French government started giving scholarships to a small number of Africans, who were sent to France to complete secondary school and go on to university. When these countries became independent, they could at least count on a small intellectual elite

.

48

,

53

In retrospect, the impact of WWII was mostly psychological. The Africans had seen that their French and Belgian masters were not all-powerful, that the Europeans could behave in a way that was far from their proclaimed ideal of civilisation and that European societies were divided rather than a homogeneous block. The independence of India sent a strong signal that colonial domination was not necessarily for ever. And anger grew against the blatant racism underlying colonialism. This came as no surprise to France and Belgium, whose governments in exile had vetoed the use of African troops to liberate the motherland,

knowing full well that this would alter the sense of inferiority that was essential to the survival of the colonial system

.

knowing full well that this would alter the sense of inferiority that was essential to the survival of the colonial system

.

On the other side of the Congo, the Belgians, although reluctant to grant any kind of political autonomy, made day-to-day life easier for the Congolese and started to consider that one of the colony’s missions was to improve the living conditions of the natives. Governor

Pierre Ryckmans, who had driven the war effort, understood that the patience of the Congolese had been stretched to the limit and a more benevolent attitude was imperative. Small-scale revolts, mutinies and labour conflicts during WWII had indicated that a wind of change was about to blow. Forced labour was abolished, African trade unions were permitted and minimum wages set. Schools, maternity hospitals and dispensaries were erected throughout the colony. Perhaps due to a gradual change in the type of manpower needed by industry (more specialised and skilled than in the early days when a pair of biceps sufficed), large employers realised that it was in their interest to stabilise their workers’ situation by facilitating familial reunification

.

49

–

50

Pierre Ryckmans, who had driven the war effort, understood that the patience of the Congolese had been stretched to the limit and a more benevolent attitude was imperative. Small-scale revolts, mutinies and labour conflicts during WWII had indicated that a wind of change was about to blow. Forced labour was abolished, African trade unions were permitted and minimum wages set. Schools, maternity hospitals and dispensaries were erected throughout the colony. Perhaps due to a gradual change in the type of manpower needed by industry (more specialised and skilled than in the early days when a pair of biceps sufficed), large employers realised that it was in their interest to stabilise their workers’ situation by facilitating familial reunification

.

49

–

50

The amount of decent urban housing was increased through a massive construction effort, and loans were made available to help people buy houses. From 1945, electricity, hitherto reserved for the Europeans, was distributed in the African sectors of Léo. Starting in 1953, family allowances were provided to married workers so that they could afford to bring their wives and children to the cities. There, up to 80% of adult men were wage earners who benefited from these allowances if their children lived with them. Urbanisation having caused hyperinflation in the value of

bridewealth, leading some men to delay the age of marriage, large companies instituted a loan programme for their employees, to help them pay the bridewealth. Despite these measures, there were so many male

migrants that the gender

imbalance persisted.

The population of Léo added 25,000 new inhabitants each year (compared to 3,500 per year in Brazza), to reach 477,000 by 1960 versus only 120,000 in Brazza and 80,000 in

Yaoundé

. The European population of the Belgian Congo also expanded considerably, reaching 113,000 in 1958, with one third living in Léo, one third in the

Katanga province and one third in the rest of the country

.

39

,

48

,

50

,

54

bridewealth, leading some men to delay the age of marriage, large companies instituted a loan programme for their employees, to help them pay the bridewealth. Despite these measures, there were so many male

migrants that the gender

imbalance persisted.

The population of Léo added 25,000 new inhabitants each year (compared to 3,500 per year in Brazza), to reach 477,000 by 1960 versus only 120,000 in Brazza and 80,000 in

Yaoundé

. The European population of the Belgian Congo also expanded considerably, reaching 113,000 in 1958, with one third living in Léo, one third in the

Katanga province and one third in the rest of the country

.

39

,

48

,

50

,

54

The post-war period saw the emergence in Léo and Brazza of a vibrant urban popular culture dominated by rumba music, a process facilitated by the extraordinary proliferation of bars of all kinds: one per 651 adults in Brazza, and one per 947 adults in Léo. This had followed

the abolition in the early 1930s of restrictions on the sale of alcohol to natives. In 1946,

Emmanuel Capelle, the Léopoldville district officer, estimated that up to 25% of income was spent on beer. In 1954, there were no fewer than 315 bars in Léo, up from about 100 ten years earlier. The triad of music, beer and dance were the pillars underlying the party atmosphere of Léo, in which the

ndumbas

(free women) were major actors, along with musicians and their bands like Papa Wendo, Joseph Kabasele’s African Jazz and Franco’s OK Jazz.

Free women and musicians were positioning themselves, consciously or not, outside the colonial order whereby everyone in the cities needed to have a well-defined occupation.

36

the abolition in the early 1930s of restrictions on the sale of alcohol to natives. In 1946,

Emmanuel Capelle, the Léopoldville district officer, estimated that up to 25% of income was spent on beer. In 1954, there were no fewer than 315 bars in Léo, up from about 100 ten years earlier. The triad of music, beer and dance were the pillars underlying the party atmosphere of Léo, in which the

ndumbas

(free women) were major actors, along with musicians and their bands like Papa Wendo, Joseph Kabasele’s African Jazz and Franco’s OK Jazz.

Free women and musicians were positioning themselves, consciously or not, outside the colonial order whereby everyone in the cities needed to have a well-defined occupation.

36

The most successful free women became bar owners, now selling beer rather than their bodies. Bars became focal points for opponents to colonialism, a place where they could discuss in

Lingala without Europeans minding. Patrice

Lumumba, the Congo’s future prime minister, spent a lot of time building support in the bars of Léopoldville and

Stanleyville. In the early 1950s, the income of wage earners in Léo increased quickly and became equivalent to that in AEF and British colonies. The gross national product of the Belgian Congo shot up by a staggering 57% between 1950 and 1954.

54

–

59

Lingala without Europeans minding. Patrice

Lumumba, the Congo’s future prime minister, spent a lot of time building support in the bars of Léopoldville and

Stanleyville. In the early 1950s, the income of wage earners in Léo increased quickly and became equivalent to that in AEF and British colonies. The gross national product of the Belgian Congo shot up by a staggering 57% between 1950 and 1954.

54

–

59

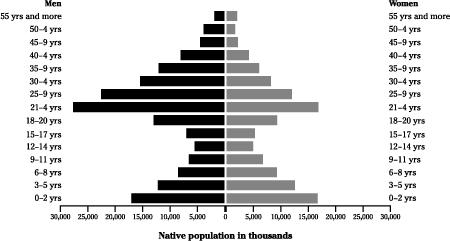

The particular situation in Léopoldville with regard to the surplus of adult men over adult women, presumably the strongest driver of prostitution, is evident in the data gathered in 1955 through a census of a representative fraction of the population of the Belgian Congo (a sample of 10% in rural and 15% in urban areas)

. In Léopoldville (population: 272,954), for adults the male/female ratio was 1.72.

In other large cities, this ratio was 1.24 in Elisabethville (population: 140,104), 1.25 in

Stanleyville (72,237), 1.16 in

Jadotville (64,937), 1.60 in

Matadi (54,840), 1.32 in

Luluabourg (43,341), 1.26 in

Coquilhatville (30,542), 1.27 in

Bukavu (30,296) and 1.24 in

Boma (24,906), the only city located close to areas inhabited by the

P.t.

troglodytes

source of HIV-1. Of course, in rural areas the opposite was seen: a surplus of women.

Figure 6

illustrates the sex and age distribution of Léopoldville’s population at the time of this census.

60

,

61

. In Léopoldville (population: 272,954), for adults the male/female ratio was 1.72.

In other large cities, this ratio was 1.24 in Elisabethville (population: 140,104), 1.25 in

Stanleyville (72,237), 1.16 in

Jadotville (64,937), 1.60 in

Matadi (54,840), 1.32 in

Luluabourg (43,341), 1.26 in

Coquilhatville (30,542), 1.27 in

Bukavu (30,296) and 1.24 in

Boma (24,906), the only city located close to areas inhabited by the

P.t.

troglodytes

source of HIV-1. Of course, in rural areas the opposite was seen: a surplus of women.

Figure 6

illustrates the sex and age distribution of Léopoldville’s population at the time of this census.

60

,

61

Figure 6

Age pyramids of Léopoldville in 1955.

Age pyramids of Léopoldville in 1955.

The distribution of men according to marital status in Léo was radically different from the rest of the country. For the whole Belgian Congo, 24% of men aged sixteen years or over had never been married, while 3% were widowed and another 3% divorced. In Léo, 42% of adult men were unmarried, 1% widowed and 2%

divorced.

Prostitution involved mostly unmarried or divorced men and women and the gender imbalance was even more marked if married people were excluded. In the unmarried/divorced category, there were 50,659 men and 9,344 women in Léo, for a 5.4 ratio. By comparison, in Elisabethville, the second largest city, there were 9,537 unmarried or divorced men, and 2,875 unmarried or divorced women, for a 3.3 ratio. In the early 1950s, Léopoldville was the city in central Africa with the highest proportion of adult men not living with a spouse, twice as high as in

Usumbura, and three times higher than in Elisabethville

. The stable overall male/female ratio in Léo in the 1950s, when the city’s population was doubling every five years, masked a much higher ratio among the unmarried portion of the population and implied a dramatic increase in the absolute number of men not living with a female spouse, and thus of potential clients for sex workers.

60

,

62

,

63

divorced.

Prostitution involved mostly unmarried or divorced men and women and the gender imbalance was even more marked if married people were excluded. In the unmarried/divorced category, there were 50,659 men and 9,344 women in Léo, for a 5.4 ratio. By comparison, in Elisabethville, the second largest city, there were 9,537 unmarried or divorced men, and 2,875 unmarried or divorced women, for a 3.3 ratio. In the early 1950s, Léopoldville was the city in central Africa with the highest proportion of adult men not living with a spouse, twice as high as in

Usumbura, and three times higher than in Elisabethville

. The stable overall male/female ratio in Léo in the 1950s, when the city’s population was doubling every five years, masked a much higher ratio among the unmarried portion of the population and implied a dramatic increase in the absolute number of men not living with a female spouse, and thus of potential clients for sex workers.

60

,

62

,

63

Other books

Open Your Legs for my Family by Aphrodite Hunt

El club de la lucha by Chuck Palahniuk

When She Was Bad... by Louise Bagshawe

Guilt by Jonathan Kellerman

Bartleby of the Big Bad Bayou by Phyllis Shalant

FIND YOUR HAPPY: An Inspirational Guide to Loving Life to Its Fullest by Kaiser, Shannon

Playing With My Heartstrings by Chloe Brewster

Maia by Richard Adams

The Hidden Coronet by Catherine Fisher

The Dancing Wu Li Masters by Gary Zukav