The Origin of Humankind (5 page)

Read The Origin of Humankind Online

Authors: Richard Leakey

The tree bore two main branches: the australopithecine species, all of which became extinct by 1 million years ago, and

Homo

, which eventually led to people like us.

Biologists who have studied the fossil record know that when a new species evolves with a novel adaptation, there is often a burgeoning of descendant species over the next few million years expressing various themes on that initial adaptation—a burgeoning known as adaptive radiation. The Cambridge University anthropologist Robert Foley has calculated that if the evolutionary history of the bipedal apes followed the usual pattern of adaptive radiation, at least sixteen species should have existed between the group’s origin 7 million years ago and today. The shape of the family tree begins with a single trunk (the founding species), spreads out as new branches evolve through time, and then reduces in bushiness as species go extinct, leaving a single surviving branch—

Homo sapiens

. How does all this match up with what we know from the fossil record?

For many years after the acceptance of

Homo habilis

, it was thought that 2 million years ago there were three australopithecine species and one species of

Homo

. We would expect the family tree to be heavily populated at this point in prehistory, so four coexisting species doesn’t sound like much. And in fact it has recently become apparent—through new discoveries and new thinking—that at least four australopithecines lived at that period, cheek by jowl with two or even three species of

Homo

. This picture is by no means settled, but if human species were like species of other large mammals (and there is no reason to think that they were not, at that point in our history), then such is what biologists would expect. The question is, What happened earlier than 2 million years ago? How many branches were there on the family tree, and what were they like?

As noted, the fossil record quickly becomes sparse beyond 2 million years ago and blank further back much more than 4 million years ago. The earliest-known human fossils are all from East Africa. On the east side of Lake Turkana, we have found an arm bone, a wrist bone, jaw fragments, and teeth from around 4 million years ago; the American anthropologist Donald Johanson and his colleagues have recovered a leg bone of similar age from the Awash region of Ethiopia. These are slim pickings indeed upon which to re-create a picture of early human prehistory. There is, however, one exception to the sparse period, and that is a rich collection of fossils from the Hadar region of Ethiopia which are between 3 million and 3.9 million years old.

In the mid-1970s, a joint French/American team, led by Maurice Taieb and Johanson, recovered hundreds of fascinating fossil bones, including a partial skeleton of one diminutive individual, who became known as Lucy (see

figure 2.3

). Lucy, who was a mature adult when she died, stood barely 3 feet tall and was extremely apelike in build, with long arms and short legs. Other fossils of individuals from the area indicated that not only were many of them bigger than Lucy, standing more than 5 feet tall, but also that they were more apelike in certain respects—the size and shape of the teeth, the protrusion of the jaw—than the hominids that lived in South and East Africa a million years or so later. This is just what we would expect to find as we moved closer and closer to the time of human origin.

When I first saw the Hadar fossils, it seemed to me that they represented two species, perhaps even more. I considered it likely that the diversity of species we see at 2 million years ago derived from a similar diversity a million years earlier, including species of

Australopithecus

and

Homo

. In their initial interpretation of the fossils, Taieb and Johanson supported this pattern of our evolution. However, Johanson and Tim White, of the University of California, Berkeley, conducted further analyses. In a paper published in the journal

Science

in January 1979, they suggested that the Hadar fossils did not represent several species of primitive human but instead were the bones of just one species, which Johanson named

Australopithecus afarensis

. The large range of body sizes, which earlier had been taken to indicate the presence of several species, was now accounted for simply as sexual dimorphism. All the known hominid species that arose later were descendants of this single species, they said. Many of my colleagues were surprised by this bold declaration, and it provoked strong debate for many years (see

figure 2.4

).

FIGURE 2.3

(RIGHT)

Lucy. This partial skeleton, known popularly as Lucy, was found in 1974 by Maurice Taieb and Donald Johanson and their colleagues, in Ethiopia. A female, Lucy stood at close to 3 feet tall. Males of her species were considerably taller. She lived a little more than 3 million years ago. (Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.)

Although many anthropologists have since decided that Johanson and White’s scheme is probably correct, I believe that the scheme is wrong, for two reasons. First, the size difference and anatomical variation in the Hadar fossils as a whole is simply too great to represent a single species. Much more reasonable is the notion that the bones came from two species, or perhaps more. Yves Coppens, who was a member of the team that recovered the Hadar fossils, also holds this view. Second, the scheme makes no biological sense. If humans originated 7 million years ago, or even only 5 million years ago, it would be highly unusual for a single species at 3 million years ago to be the ancestor of all later species. This would not be the typical shape of an adaptive radiation, and unless there is good reason to suspect otherwise we must consider human history to have followed the typical pattern.

The only way this issue will be resolved to everyone’s satisfaction is through the discovery and analysis of more fossils older than 3 million years, which seemed possible early in 1994. After a decade and a half of being unable, for political reasons, to return to the fossil-rich sites in the Hadar region, Johanson and his colleagues have made three expeditions since 1990. Their efforts have met with great success, being rewarded with the recovery of fifty-three fossil specimens, including the first complete cranium. The pattern seen previously from this time period—that of a great range of body sizes—is confirmed and even extended by the new finds. How is this fact to be interpreted? Is the issue of one species or more at the brink of resolution?

Unfortunately it is not. Those who considered that the size range of the previously discovered fossils indicated a difference in stature between males and females viewed the new ones as supporting that position. Those of us who suspected that so broad a size range must indicate a difference between species, not a within-species difference, interpreted the new fossils as strengthening that view. The shape of the family tree earlier than 2 million years ago must therefore be regarded as an unresolved question.

The discovery of the Lucy partial skeleton in 1974 seemed to offer the first glimpse of the degree of anatomical adaptation to bipedal locomotion in an early hominid. By definition, the first hominid species to have evolved, some 7 million years ago, would have been a bipedal ape of sorts. But until the Lucy skeleton came along, anthropologists had no tangible evidence of bipedalism in a human species older than about 2 million years. The bones of the pelvis, legs, and feet in Lucy’s skeleton were vital clues to this question.

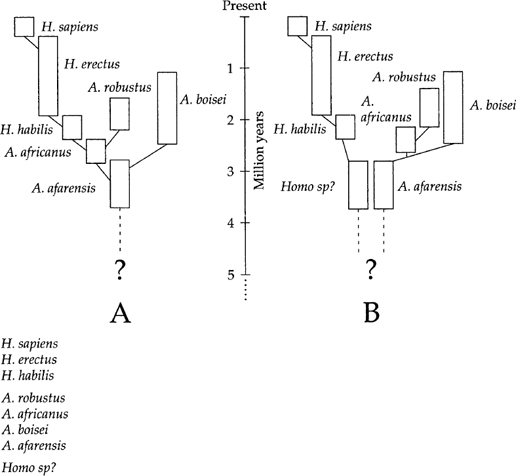

Family trees. The existing fossil evidence is interpreted differently by different scholars, although the overall shape of the inferred evolutionary history is similar. Two versions are presented here, somewhat simplified. My preference is for B, in which specimens of the genus

Homo

are among the earliest known fossils; this would be ancestral to what we know as

Homo habilis

. The fossil record does not extend back as far as the origin of the human family—some 7 million years ago, as inferred from molecular genetic evidence.

From the shape of the pelvis and the angle between the thighbone and knee, it is clear that Lucy and her fellows were adapted to some form of upright walking. These anatomical features were much more humanlike than apelike. In fact, Owen Lovejoy, who performed the initial anatomical studies on these bones, concluded that the species’ bipedal locomotion would have been indistinguishable from the way you and I walk. Not everyone agreed, however. For instance, in a major scientific paper in 1983 Jack Stern and Randall Susman, two anatomists at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, offered a different interpretation of Lucy’s anatomy: “It possesses a combination of traits entirely appropriate for an animal that had traveled well down the road toward full-time bipedality, but which retained structural features that enabled it to use the trees efficiently for feeding, sleeping or escape.”

One of the crucial pieces of evidence that Stern and Susman adduced in favor of their conclusion was the structure of Lucy’s feet: the bones are somewhat curved, as is seen in apes but not in humans—an arrangement that would facilitate tree climbing. Lovejoy discounts this view and suggests that the curved foot bones are a mere evolutionary vestige of Lucy’s apelike past. These two opposing camps enthusiastically maintained their differences of opinion for more than a decade. Then, early in 1994, new evidence, including some from a most unexpected source, seemed to tip the balance.

First, Johanson and his colleagues reported the discovery of two 3-million-year-old arm bones, an ulna and a humerus, that they attribute to

Australopithecus afarensis

. The individual had obviously been powerful, and its arm bones had some features similar to those seen in chimpanzees while others were different. Commenting on the discovery, Leslie Aiello, an anthropologist at University College, London, wrote in the journal

Nature:

“The mosaic morphology of the

A. afarensis

ulna, together with the heavily muscled and robust humerus, would be ideally suited to a creature which climbed in the trees but also walked on two legs when on the ground.” This description, which I support, clearly fits closely with the Susman camp and not the Love joy camp.

Even stronger support for this view comes from the innovative use of computerized axial tomography (CAT scanning) to discern the details of the inner ear anatomy of these early humans. Part of the anatomy of the inner ear are three C-shaped tubes, the semicircular canals. Arranged mutually perpendicular to each other, with two of the canals oriented vertically, the structure plays a key role in the maintenance of body balance. At a meeting of anthropologists in April 1994, Fred Spoor, of the University of Liverpool, described the semicircular canals in humans and apes. The two vertical canals are significantly enlarged in humans compared with those in apes, a difference Spoor interprets as an adaptation to the extra demands of upright balance in a bipedal species. What of early human species?

Spoor’s observations are truly startling. In all species of the genus

Homo

, the inner ear structure is indistinguishable from that of modern humans. Similarly, in all species of

Australopithecus

, the semicircular canals look like those of apes. Does this mean that the australopithecines moved about as apes do—that is, quadrupedally? The structure of the pelvis and lower limbs speaks against this conclusion. So does a remarkable discovery my mother made in 1976: a trail of very humanlike footprints made in a layer of volcanic ash some 3.75 million years ago. Nevertheless, if the structure of the inner ear is at all indicative of habitual posture and mode of locomotion, it suggests that the australopithecines were not just like you and me, as Love joy suggested and continues to suggest.

In promoting his interpretation, Lovejoy seems to want to make hominids fully human from the beginning, a tendency among anthropologists that I discussed earlier in this chapter. But I see no problem with imagining that an ancestor of ours exhibited apelike behavior and that trees were important in their lives. We are bipedal apes, and it should not be surprising to see that fact reflected in the way our ancestors lived.