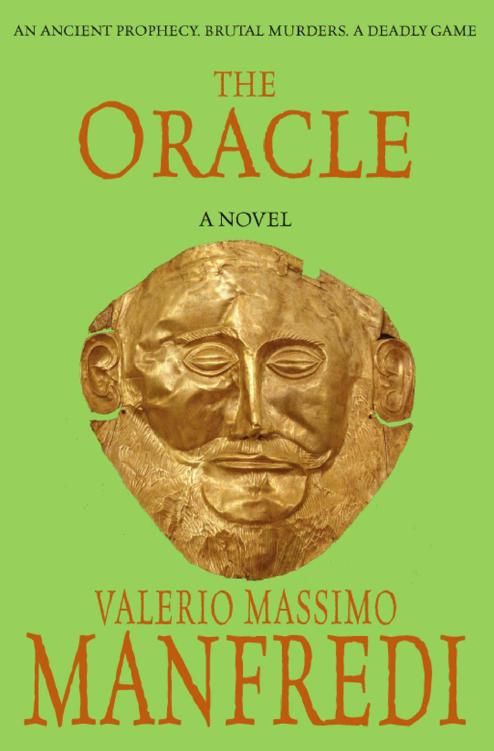

The Oracle

Authors: Valerio Massimo Manfredi

V

ALERIO

M

ASSIMO

M

ANFREDI

Translated from the Italian by Christine Feddersen-Manfredi

PAN BOOKS

Contents

F

OR

C

HRISTOS AND

A

LEXANDRA

M

ITROPOULOS

My name is Nobody: mother, father and friends, everyone calls me Nobody.

Homer,

Odyssey

IX, 366–7

Ephira, north-western Greece, 16 November 1973, 8 p.m.

T

HE TIPS OF

the fir trees trembled suddenly. The dry oak and plane leaves shuddered, but there was no wind and the distant sea was as cold and still as a slab of slate.

It seemed to the old scholar as if everything around him had suddenly been silenced – the chirping of the birds and the barking of the dogs and even the voice of the river, as if the water were lapping the banks and the stones on its bed without touching them. As if the earth had been shaken by a dim, deep tremor.

He ran his hand through his white hair, thin as silk. He touched his forehead and tried to find within himself the courage to face – after thirty years of obstinate, tireless research – the vision he had sought.

No one was there to share the moment with him. His workers, Yorgo the drunk and Stathis the grumbler, had already left after having put away their tools, their hands deep in their pockets and their collars turned up. Their footsteps on the gravelly road were the only sound to be heard.

Anguish gripped the old man. ‘Ari!’ he shouted. ‘Ari, are you still there?’

The foreman rushed over: ‘I’m right here, Professor. What is it?’

But it was just a moment’s weakness: ‘Ari, I’ve decided to stay a little longer. You go on to town. It’s dinner time, you must be hungry.’

The foreman looked him over with a mixture of affection and protectiveness: ‘Come with me, Professor. You need to eat something and to rest. It’s getting cold, you’ll catch your death out here.’

‘No, I’ll just be a little while, Ari. You go on ahead.’

The foreman walked off reluctantly, got into the service car and headed down the road to town. Professor Harvatis watched the car’s lights slash the hillside. He then went into the little tool shed, resolutely took a shovel from its hook on the wall, lit a gas lamp and started towards the entrance to the building which housed the ancient Necromantion: the Oracle of the Dead.

At the end of the long central corridor were the steps that he had unearthed over the last week. He started down, going much deeper than the sacrifice chamber, and ended up in a room still cluttered by the dirt and stones that hadn’t been cleared away. He looked around, sizing up the small space that surrounded him, and then took a few steps towards the western wall until he was in the centre of the room. His shovel scraped away the layer of dirt covering the floor until the tip of the tool hit a hard surface. The old man pushed aside the dirt, uncovering a stone slab. It was engraved with the figure of a serpent, the cold symbol of the other world.

He took the trowel from his jacket pocket and scraped all around the slab to loosen it. He stuck the tip of the trowel into a crack and prised up the slab by a few centimetres, then flipped it back. An odour of mould and moist earth invaded the small chamber.

A black hole was open before him, a cold, dark recess never before explored. By anyone. This was the

adyton

: the chamber of the secret oracle. The place in which only a very few initiates had ever been admitted, with one purpose. To call up the pale larvae of the dead.

He lowered his lamp and saw yet more stairs. He felt his life quivering within him like the flame of a candle just before it goes out.

By night

our ship ran onward towards the Ocean’s bourne,

the realm and region of the Men of Winter,

hidden in mist and cloud. Never the flaming

eye of Helios lights on those men

at morning, when he climbs the sky of stars,

nor in descending earthward out of heaven;

ruinous night being rove over those wretches.

He recited Homer’s verses under his breath like a prayer: they were the words of the Nekya, the eleventh book of the

Odyssey

, recounting Odysseus’s journey to the realm of the shades.

The old man descended to the second underground chamber and raised his lamp to see the walls. His brow wrinkled and beaded up with sweat: the lamplight danced all around him guided by his trembling hand, revealing the scenes of an ancient, terrible rite – the sacrifice of a black ram, blood dripping from his gashed neck into a pit. He stared at the faded figures, eaten away by the damp. He stumbled closer and saw that there were names, people’s names, cut into the wall. Some he recognized, great persons from the distant past, but many were incomprehensible, carved in letters unknown to him. He stepped back and the lamplight returned to the scene of the sacrifice. More words escaped his lips:

With my drawn blade

I spaded up the votive pit, and poured

libations round to it the unnumbered dead:

sweet milk and honey, then sweet wine, and last

clear water; and I scattered barley down.

Then I addressed the blurred and breathless dead . . .

He walked to the centre of the chamber, knelt down and began to dig with his bare hands. The earth was cold and his fingers numb. He stopped to warm his stiffened hands under his armpits; his breath was fogging up his eyeglass lenses and he had to take them off to dry them. He began digging again, and his fingers found a surface as smooth and cold as a piece of ice; he pulled them back as if he had been bitten by a snake nesting in the mud. His eyes jerked to the wall in front of him; he had the sensation that it was moving. He took a deep breath. He was tired, he hadn’t eaten all day: an illusion, certainly.

He plunged his hands back into the mud and felt that same surface again. Smooth, perfectly smooth. His fingers ran over it, all around it, clearing off the mud as best he could. He brought the lamp close. Under the brown earth, the cold, pale glitter of gold.

He dug with fresh energy, and the rim of a vase soon appeared. A Greek crater, incredibly beautiful and minutely crafted, was buried in the dirt at the exact centre of the room.

His hands moved quickly and expertly and, under the feverish digging of his long, lean fingers, the fabulous vase seemed to emerge from the earth as if animated by an invisible energy. It was very, very ancient, entirely decorated with parallel bands. A large medallion at the centre was engraved with a scene in relief.

The old man felt tears come to his eyes and emotion overwhelm him: was this the treasure he’d been searching for his whole life? Was this the very core of the world? The hub of the eternal wheel, the centre of the known and the unknown, the repository of light and darkness, gold and blood?

He put down the lamp and stretched his trembling hands towards the large glittering vase. He closed his hands around it and lifted it up to his face, and his eyes filled with even greater stupor: the medallion at the centre depicted a man on foot armed with a sword, with something raised to his shoulder: a long handle . . . or an oar. Facing him was another man, dressed as a wayfarer, who lifted his hand as if to question him. Between them, an altar, and next to it three animals: a bull, a ram and a boar.

Great God in heaven! The prophecy of Tiresias engraved in gold before his eyes, the prophecy which announced Odysseus’s last voyage . . . The voyage that no one had ever described, the story that had never been told. A journey over dry land, an odyssey through mud and dust towards a forgotten land, at a great distance from the sea. To a place where people had never heard of salt, or of ships, where no one would recognize an oar, and could mistake it for a winnow, a fan used for separating the chaff from the grain.

He turned the great vase over in his hands and saw other scenes; they leapt to life, animated by the lamplight dancing on their surface. Odysseus’s last adventure, cruel and bloody, in fulfilment of a fate he could not escape . . . forced to travel so far from the sea, only to return to the sea . . . to die.

Periklis Harvatis held the vase against his chest and raised his eyes to the northern wall of the

adyton

.

It was open.

Dumbfounded, he found himself facing a narrow opening, an impossible, absurd gap in the inert stone. It must have always been there, he reasoned, perhaps he just hadn’t noticed it in the wavering light of the lamp. But deep inside, he realized with merciless certainty that he had somehow forced open that dim, threatening aperture. He took a few steps forward, still holding the vase, and picked up a little stone. He threw it into the opening. The stone was swallowed up without making a sound, neither when he hurled it nor after.

Was the abyss without end?

He moved forward to put an end to these dark imaginings. ‘No!’ he roared out, with everything he had in him. But his voice did not sound at all. It imploded within him, obliterating every scrap of strength. He felt his legs collapsing as he was invaded by intense cold, overwhelmed by crushing pressure. That hole was stronger than anyone and anything, it would suck up and devour any living energy.

But how could he turn back now? What meaning would his life have? Hadn’t he been pursuing, for years and years, the proof for his theories, so often ridiculed? He was still in the real world, after all. He would go forward. He held out the lamp with one hand and gripped his treasure to his chest with the other.