The Opposite of Fate (22 page)

Read The Opposite of Fate Online

Authors: Amy Tan

When we returned to the village, lo and behold, the matter had been settled. The villagers presented us with a bill itemizing each of their demands, and all this was tallied to the grand sum of a little more than 5,000 renmenbi. That was one-eighth of what we had offered in U.S. dollars. Someone tactfully pointed out the error, but whether out of pride or a deep suspicion of

American dollars, the villagers stuck to the lesser sum. Among our Chinese crew, we were able to scrounge together enough to pay them off. All were happy and filming began.

In our final village, we wound up restarting World War II. The location was a huge pasture with hills in the background that looked like gigantic ancient fish stuck tail-down into the earth. A long dirt road bisected this valley. A thousand extras were on hand, some in 1940s clothes and clinging to their most precious worldly possessions, a sack of rice, a suitcase, a pair of babies. The rest were in the uniforms of the Kuomintang, the Nationalist army, defeated by the Japanese in Kweilin (Guilin). Some walked by with bandages around their heads. Some had limbs missing and were on crutches. A burning jeep lay upturned. Watching the shoot were some locals, as well as members of the People’s Army, who served as security.

Food arrived, box lunches for a thousand catered by the Sheraton Hotel in Guilin. It was pretty fancy fare by local standards, a meal that cost an average week’s salary. When lunch was over, we had a few dozen boxes left, and someone from the American crew thoughtfully called out to onlookers that they were welcome to take them. Shouts immediately erupted among the extras. They wanted the leftovers: they had earned them, and they would keep them. All at once, fists were flying, people were being shoved, and the Kuomintang was fighting the People’s Army. It was war all over again. Luckily, no one was seriously injured. Filming resumed with our extras looking even more tattered than before. Talk about Method acting.

Months later, one of the most curious comments I heard during a test-audience focus-group session involved the scenes shot

in China. To me, these scenes are stunning—so stunning they strain credibility. A woman in the focus group said, “All the scenes were gorgeous—until we got to China. You should get rid of those matte paintings. You can tell they’re fake.” I turned to Wayne and poked him. “See? We didn’t have to suffer in China. We could have used better matte paintings.”

I Cried My Eyes Out

Moviemaking, I learned, is an emotionally draining experience. I was moved by seeing the realism of the sets, the authentic touches, and hearing the private revelations made to me by the actors, stars as well as extras, about why being in this movie meant so much to them.

During filming in the States, I began each day by popping in a videotape of the previous day’s filming that had been delivered to me at home by messenger, and then I would cry my eyes out. I was amazed that the scenes I had seen enacted before me had assumed that real movie quality on film. A strange transformation had taken place, as if this reel life were more real than real life. But that’s what movies are all about.

At major stages, Ron and I worked with Wayne and the editor, Maysie Hoy, as the movie was being cut. That process was fascinating but tedious, a matter of deciding over milliseconds. Our movie was running way too long, and to get it into theaters meant every one of those cuts was essential. Through meticulous editing, milliseconds could add up to minutes, and in the end it would seem as if nothing had been cut. I ended up thinking Maysie was a saint.

Around April, I saw the first rough cut. I was supposed to take notes of problem areas and such. Yet I was too mesmerized to do anything but watch it like an ordinary moviegoer. I laughed, I cried. The second time I saw it, I told Wayne: “I want you to remember this day. We’re going to get a lot of different reactions to this film later. But I want us to remember that on this day, you, Ron, and I were proud of what we’d accomplished. We made our vision.”

Ron insisted that I come to test previews because there, seeing how a real audience reacted, I’d get some of the biggest highs—or lows—of my life. Fortunately, it was the former. I was surprised, though, when people laughed during scenes I never considered funny. I suppose those were ironic laughs, in response to recognizing the pain of some past humiliation.

I’ve now seen the movie about twenty-five times, and I am not ashamed to say I’ve been moved to tears each time.

By the time you read this, I will have seen the movie with my mother and my half sister, who just immigrated from China. She is one of the daughters my mother had to leave behind when she came to the United States. So that will be my version of life imitating art, or sitting in front of it. I’m nervous about what my mother will think. I’m afraid she’ll be overwhelmed by some of the scenes that are taken from her life, especially the one that depicts the suicide of her mother.

*

I hope audiences are moved by the film, that they connect with the emotions and feel changed at the end, that they feel

closer to other people as a result. That’s what I like to get out of a book, a connection with the world.

As to reviews, I’ve already imagined all the bad things that can be said. That way I’ll be delighted by anything good that comes out. I’m aware that the success of this movie will depend on good reviews and word of mouth. But there comes a point when you’ve done all you can. And then it’s out of your control. Certainly I hope the movie is a success at the box office, mostly for Wayne’s and Ron’s sakes, as well as for the cast and crew who dedicated themselves in a manner that made me feel it was not “just another job” for them. And certainly I hope Disney thinks it was more than justified in taking a risk on this movie. By my score, however, the movie is already a success. We made the movie we wanted to make. It’s not perfect, but we’re happy with it. And I’ll be standing in line, ready to plunk down seven dollars to see it.

In the meantime, I have a whole mess of Chinese lucky charms absolutely guaranteed to bring the gods to the theater.

I’ve Learned My Lessons

At various times in the making of the movie, I vowed I’d never do this again. It’s too time-consuming. There are too many ups-and-downs. There’s so much business, too many meetings. I’ve developed calluses and sangfroid about some of the inherent difficulties of filmmaking.

Yet against all my expectations, I like collaborating from time to time. I like fusing ideas into one vision. I like seeing that vision come to life with other people who know exactly what it takes to get there.

My love of fiction is unaltered. It’s my first love. But yes, I’ll make another film with Ron and Wayne. It will probably be of my second book,

The Kitchen God’s Wife.

We’ve already started breaking the scenes out with page counts and narrative text. We began the day after we saw the rough cut of

The Joy Luck Club.

*

STRONG WINDS, STRONG INFLUENCES

I was six when my mother taught me the art of invisible strength. It was a strategy for winning arguments, respect from others, and eventually, though neither of us knew it at the time, chess games.

•

The Joy Luck Club

I

n 1988, I received a contract to write a book titled

The JoyLuck Club.

I had completed three stories, and I had thirteen proposed stories to go, many of which were supposed to be set in China, more than a few of them during World War II.

Months before, I had hastily outlined these story ideas in a proposal that my new editor had bought. I believed I was not to deviate from this plan, and now I was worried over the parts that involved the war, a subject I was ill equipped to write about. It was time to do some serious research.

I called my mother. “Hey, Ma, what was it like during the war?”

My mother considered the question, paused to cast back to her life in China. “War? Oh, I was not affected.”

I assumed by her answer that she had been tucked away in free China, that her experiences with World War II were similar to mine with Vietnam: observed from a safe distance. Ah well, some parents have interesting war stories to tell. My mother did not.

So it was not until later in our conversation that I learned what my mother really meant by her answer. She was telling me

about her first marriage, to a pilot to whom she could never refer by name, only by the words “that bad man.” And now, she told me, somebody had sponsored that bad man to come visit the United States as a former Kuomintang hero.

“Hnh! He was no hero!” my mother exclaimed. “He was dismissed from air force for bad morals.” And she began to tell me details of their life in China—of bombs falling, of running to escape, of pilot friends who showed up for dinner one week and were dead the next.

I interrupted her. “Wait a minute, I thought you said you weren’t affected by the war.”

“I wasn’t,” insisted my mother. “I wasn’t killed.”

Her answer made me realize, once again, that my mother and I were at times oceans apart in our view of the world. When I was growing up, I too was “not affected.” I had no idea that China had ever been involved in World War II—let alone that the war in China had started in 1937. And for the first ten years of my life, I did not know of my mother’s first marriage. She kept it a secret from my brothers and me, from her closest friends. When she finally did tell me, I did not ask her any questions. In part, I did not want to think that she could have once loved a man other than my father. And when I grew older, I still did not ask her about her early life in China. Why bring up the pains of her past? Of course, the questions were still there. I wondered, I imagined, I assumed what the answers might have been.

When I set out to write my second book, I remembered that conversation with my mother, about her marriage to a man she grew to despise. I decided to write about a woman and her secret regrets, and used my American assumptions to shape the story:

that this woman’s first marriage, while ending in hate, surely must have been born out of love. Why else would she have stayed in her marriage for twelve years?

That’s what I started out writing. Fortunately, writing has a way of showing me how false my assumptions can be. My character rebelled against this fiction I had imposed on her. “No,” she protested. “This was not love. This was hope, hope for myself.” She refused to go along with the plot, and I found the story at a dead end.

And so I began again. I began by asking myself about hope. How does it change, transform, endure according to life’s quirky circumstances? And what of the circumstances themselves: Do we believe they are simply a matter of fate? Or do we view them as the Chinese concept of luck, the Christian concept of God’s will, the American concept of choice? And depending on what we believe, how can we find balance in our lives? What do we accept? What do we feel we can still change?

Eventually I wrote a book in which a mother poses these questions as she tells her daughter the secrets of her past. Since the story takes place during wartime, before my birth, I had to do quite a bit of research. I read scholarly texts and revisionist versions of the various roles of the Kuomintang, the Communists, the Japanese, and the Americans. I read wartime accounts published in popular periodicals—with different perspectives on these same groups. And of course, I needed a personal account of the war years to fact-check some of the mundane details of my story: How long did it take to travel from Shanghai to Yang-chow? What was a typical dowry for a bride from a well-to-do family? For those answers, I went to my mother, who in

response gave me more than I asked for. The question of the dowry alone led to a three-hour remembrance of things past—not simply about wedding gifts, but about family gossip and Shanghai manners, about a gangster who showed up at her wedding, about her innocence—her stupidity!—in marrying a man she hardly knew.

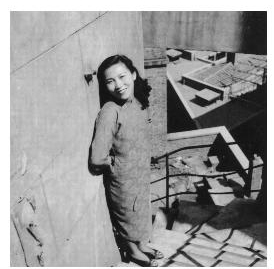

My mother, photographed by my father, Tientsin, China, 1945.

I know readers will wonder: How much of the story is true? With

The Joy Luck Club

, I met readers who assumed everything in my book was true, my fiction simply a matter of fast dictation and an indelible memory. My mother complained of having to deny over and over that she was one or all of the mothers in my

first book. “It’s all fiction,” she told her friends. “None of it is true. My daughter just has a wild imagination.”

While I was writing my second book, she made sure to give me some motherly advice. “This time,” she said, “tell my

true

story.” And with her permission—actually, her

demand

—how could I refuse? How could I resist? After all, the richest source of my fiction does come from life as I have misunderstood it—its contradictions, its unanswerable questions, its unlikely twists and turns.

So, indeed, some of the events in

The Kitchen God’s Wife

are based on my mother’s life: her marriage to “that bad man,” the death of her children, her fortuitous encounter with my father. But with apologies to my mother, I confess that I changed her story. I invented characters who never existed in her life: Auntie Du, Helen, Jiaguo, Old Aunt and New Aunt, Peanut, Beautiful Betty, Bao-Bao Roger. I took her to places that do not exist: to a tea-growing monastery in Hangchow, to a mountaintop village called Heaven’s Breath, to a scissors-making shop in Kunming, to an American dance that in real life she decided not to attend. With those imaginary details in place, I can honestly say the story is fiction, not true.