The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (37 page)

You think that winning sets you

FREE

?

The topmost free end-line is

STICKS

:

No, it’s a poison pill that

STICKS

Then

FOR, WON, TO

and

THRIVE

: The homophone

WON

is perfectly acceptable for

ONE

.

In victory’s throat. Worth striving

FOR

?

The golden plaudits you have

WON

Are valueless and hollow

TOO

The victor’s laurels never

THRIVE

,

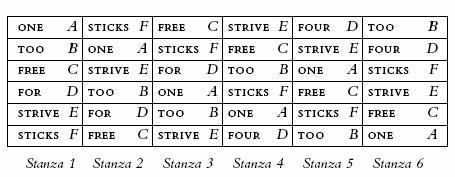

Now we do the same to

Stanzas 4, 5

and

6

, shuttling between lines 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, in formula order.

The weeds of self-delusion

THRIVE

On pride: they flourish, thick and

FREE

,

To choke your glory. Thickly

TOO

The burr of disappointment

STICKS

To tarnish all the gold you’ve

WON

.

Is victory worth the fighting

FOR

When friendship’s hand is only

FOR

The weak, whose ventures never

THRIVE

?

I’d so much rather be the

ONE

Who’s always second. I am

FREE

To lose. I know how much it

STICKS

Inside your craw to come in

TWO

But you should learn that Number

TWO

Can have no real meaning,

FOR

We all must cross the River

S

TYX

And go where victors never

THRIVE

,

No winner’s rostrum there, so

FREE

Your mind from numbers: Death has

WON

.

The sixth is the last, after that the whole pattern would repeat. All we have to do now is construct the envoi, which contains all the hero words

12

in a strict order: the second and fifth word in the top line, the fourth and third in the middle line, the sixth and first in the bottom line.

Envoi

In order

TO

improve and

THRIVE

Stop yearning

FOR

success, be

FREE

If this rule

STICKS

then all have

WON

.

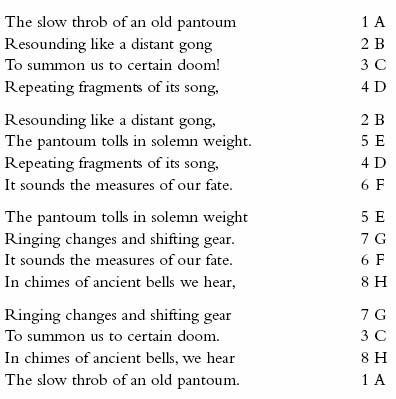

It may have seemed a fiendishly complicated structure and it both is and isn’t. The key is to number the lines and follow the 6, 1, 5, 2, 4, 3 formula with (2–5, 4–3, 6–1 for the envoi). If you don’t like numbers you might prefer to

letter

the lines alphabetically and make a note of this scheme:

ABCDEF, FAEBDC, CFDABE, ECBFAD, DEACFB, BDFECA

(

BE/DC/FA

)

If you want to understand the sestina’s shape, you might like to think of it as a spiral. Go back and put the tip of your forefinger on

STICKS

in

Stanza 1

, without taking it off the page move it in an anticlockwise circle passing through 1, 5, 2, 4 and 3. Do it a couple of times so you get the idea. I have made a table which you might find useful. It contains the end-lines of the sestina we built together, as well as ABC equivalents.

Sestina Table

I was rather fascinated by why a sestina works the way it does and whether it could be proved mathematically that you only need six stanzas for the pattern to repeat. Being a maths dunce, I approached my genius of a father who can find formulas for anything and he offered an elegant mathematical description of the sestina, showing its spirals and naming his algorithm in honour of Arnaud Daniel, the form’s inventor, who was something of a mathematician himself, so legend has it. This mathematical proof can be found in the Appendix. If like me, formulae with big Greek letters in them mean next to nothing, you will be as baffled by it as I am, but you might like, as I do, the idea that even something as ethereal, soulful and personal as a poem can be described by numbers…

Sestinas are still being written by contemporary poets. After their invention by the twelfth-century mathematician and troubadour Arnaud Daniel, examples in English have been written by poets as varied in manner as Sir Philip Sidney, Rossetti, Swinburne, Kipling, Pound, W. H. Auden, John Ashbery, Anthony Hecht, Marilyn Hacker, Donald Justice, Howard Nemerov and Kona Macphee (see if you can find her excellent sestina ‘IVF’). Swinburne’s ‘A Complaint to Lisa’ is a

double sestina

, twelve stanzas of twelve lines each, a terrifying feat first achieved by Sir Philip Sidney. I mean surely that’s just showing off…. I shall present two examples to show the possibilities of a form which my sample verse has made appear very false and stagy. The first is by Elizabeth Bishop, entitled simply ‘Sestina’, flowing between ten-, nine-and eight-syllable lines, ending with a final line of twelve:

September rain falls on the house.

In the failing light, the old grandmother

sits in the kitchen with the child

beside the Little Marvel Stove,

reading the jokes from the almanac,

laughing and talking to hide her tears.

She thinks that her equinoctial tears

and the rain that beats on the roof of the house

were both foretold by the almanac,

but only known to a grandmother.

The iron kettle sings on the stove.

She cuts some bread and says to the child,

It's time for tea now; but the child

is watching the teakettle's small hard tears

dance like mad on the hot black stove,

the way the rain must dance on the house.

Tidying up, the old grandmother

hangs up the clever almanac

on its string. Birdlike, the almanac

hovers half open above the child,

hovers above the old grandmother

and her teacup full of dark brown tears.

She shivers and says she thinks the house

feels chilly, and puts more wood in the stove.

It was to be, says the Marvel Stove.

I know what I know, says the almanac.

With crayons the child draws a rigid house

and a winding pathway. Then the child

puts in a man with buttons like tears

and shows it proudly to the grandmother.

But secretly, while the grandmother

busies herself about the stove,

the little moons fall down like tears

from between the pages of the almanac

into the flower bed the child

has carefully placed in the front of the house.

Time to plant tears, says the almanac.

The grandmother sings to the marvelous stove

and the child draws another inscrutable house.

It is not considered

de rigueur

these days to enforce the end-word order of the envoi. This next (also called ‘Sestina’) is by the poet Ian Patterson–wonderful how his end-words slowly cycle their multiple meanings:

Autumn as chill as rising water laps

and files us away under former stuff

thinly disguised and thrown up on a screen;

one turn of the key lifts a brass tumbler–

another disaster probably averted, just,

while the cadence drifts in dark and old.

Voices of authority are burning an old

car on the cobbles, hands on their laps,

as if there was a life where just

men slept and didn’t strut their stuff

on stage. I reach out for the tumbler

and pour half a pint behind the screen.

The whole body is in pieces. Screen

memories are not always as sharp as old

noir phenomena. The child is like a tumbler

doing back-flips out of mothers’ laps

into all that dark sexual stuff

permanently hurt that nothing is just.

I’m telling you this just

because I dream of watching you behind a screen

taking your clothes off for me: the stuff

of dreams, of course. Tell me the old, old

story, real and forgetful. Time simply laps

us up, like milk from a broken tumbler.

A silent figure on the stage, the tumbler

stands, leaps and twists. He’s just

a figure of speech that won’t collapse

like the march of time and the silver screen;

like Max Wall finally revealing he was old

and then starting again in that Beckett stuff.

I’d like to take my sense of the real and stuff

it. There’s a kind of pigeon called a tumbler

that turns over backwards as it flies, old

and having fun; sometimes I think that’s just

what I want to do, but I can’t cut or screen

out the lucid drift of memory that laps

my brittle attention just off-screen

away from the comfortable laps and the velvety stuff

I spilled a tumbler of milk over before I was old.

What seems like a silly word game yields poetry of compelling mystery and rhythmic flow. What appear to be the difficulties of the form reveal themselves, as of course they should, as its strengths–the repetition and recycling of elusive patterns that cannot be quite held in the mind all at once. Much in experience and thought deserves a poetic form that can bring such elements to life.

Poetry Exercise 15

Well, all you have to do now is write your own. It will take some time: do not expect it to be easy. If you get frustrated, walk away and come back later. Let ideas form in your mind, vanish, reform, change, adapt. The repetition of end-words in the right hands works in favour of the poem: it is a defining feature of the form, not to be disguised but welcomed. You might harness this as a means of repeating patterns of speech, as we all do in life, or in reflecting on the same things from different angles.

You can do it, believe me you can. And you will be so

proud of yourself

!

T

HE

P

ANTOUM