The ode less travelled: unlocking the poet within (35 page)

There was an Anacreontic Society in the eighteenth century dedicated to ‘wit, harmony and the god of wine,’ though its real purpose became the convivial celebration of music, hosting evenings for Haydn and other leading musicians of the day, as well as devising their own club song: ‘To Anacreon in Heav’n’. A society member, John Stafford Smith, wrote the music for it, a tune which somehow got pinched by those damn Yankees who use it to this day for their national anthem, ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’–‘Oh say can you see, by the dawn’s early light’ and so on. Strange to think that the music now fitting

…yet wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

was actually written to fit

…entwine

The myrtle of Venus with Bacchus’s wine!

And this in a country where they prohibited alcohol for the best part of a quarter of a century, a country where they look at you with pitying eyes if you order a weak spritzer at lunchtime. Tsch!

The poet most associated with English anacreontics is the seventeenth-century Abraham Cowley: here he is extolling Epicureanism over Stoicism in ‘The Epicure’:

Crown me with roses while I live,

Now your wines and ointments give:

After death I nothing crave,

Let me alive my pleasures have:

All are Stoics in the grave.

And a snatch of another, simply called ‘Drinking’:

Fill up the bowl then, fill it high,

Fill all the glasses there, for why

Should every creature drink but I,

Why, man of morals, tell me why?

Three hundred years later one of my early literary heroes, Norman Douglas, observing a wagtail drinking from a birdbath, came to this conclusion:

Hark’ee, wagtail: Mend your ways;

Life is brief, Anacreon says,

Brief its joys, its ventures toilsome;

Wine befriends them–water spoils ’em.

Who’s for water? Wagtail, you?

Give me wine! I’ll drink for two.

One of the enduring functions of all art from Anacreon to Francis Bacon, from Horace to Damien Hirst has been, is and always will be to remind us of the transience of existence, to stand as a

memento mori

that will never let us forget Gloria Monday’s sick transit. We do, of course,

know

that we are going to die, and all too soon, but we need art to remind us not to spend too much time in the office caring about things that on our deathbeds will mean less than nothing. The particularity of anacreontics (simply writing in seven-syllable trochaic tetrameter as above does not make your verse anacreontic: the verse

must

concern itself with pleasure, wine, erotic love and the fleeting nature of existence) is echoed in the contemplative odes and love poetry of Horace; we find it in Shakespeare, Herrick, Marvell and all poetry between them and the present day. It is also a theme of Middle-Eastern poetry, Hafiz (sometimes called the Anacreon of Persia) and Omar Khayyam most notably.

What of Dylan Thomas’s ‘In My Craft or Sullen Art’?

In my craft or sullen art

Exercised in the still night

When only the moon rages

And the lovers lie abed

With all their griefs in their arms,

I labour by singing light

Not for ambition or bread

Or the strut and trade of charms

On the ivory stages

But for the common wages

Of their most secret heart.

Wonderful as the poem is, dedicated to lovers as it is, presented in short sweet lines as it is, it would be bloody-minded to call it anacreontic: a hint of Eros, but no sense of Dionysus or of the need to love or drink as time’s winged chariot approaches. However, I would call one of the most beautiful poems in all twentieth-century English verse, Auden’s ‘Lullaby’ (1937), anacreontic, although I have never seen it discussed as such. Here are a few lines from the beginning:

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm;

Time and fevers burn away

Individual beauty from

Thoughtful children, and the grave

Proves the child ephemeral:

But in my arms till break of day

Let the living creature lie,

Mortal, guilty, but to me

The entirely beautiful.

The references to flesh, love and the transience of youth make me feel this does qualify. I have no evidence that Auden thought of it as anacreontic and I may be wrong. Certainly one feels that not since Shakespeare’s earlier sonnets has any youth had such gorgeous verse lavished upon him. I dare say both the subjects proved unworthy (the poets knew that, naturally) and both boys are certainly dead–the grave

has

proved the child ephemeral.

Ars longa, vita brevis

:

9

life is short, but art is long.

VI

Closed Forms

Villanelle–sestina–ballade, ballade redoublé

Certain closed forms, such as those we are going to have fun with now, seem demanding enough in their structures and patterning to require some of the qualities needed for so-doku and crosswords. It takes a very special kind of poetic skill to master the form

and

produce verse of a quality that raises the end result above the level of mere cunningly wrought curiosity. They are the poetic equivalent of those intricately carved Chinese étuis that have an inexplicable ivory ball inside them.

T

HE

V

ILLANELLE

Kitchen Villanelle

How rare it is when things go right

When days go by without a slip

And don’t go wrong, as well they might.

The smallest triumphs cause delight–

The kitchen’s clean, the taps don’t drip,

How rare it is when things go right.

Your ice cream freezes overnight,

Your jellies set, your pancakes flip

And don’t go wrong, as well they might

When life’s against you, and you fight

To keep a stiffer upper lip.

How rare it is when things go right,

The oven works, the gas rings light,

Gravies thicken, potatoes chip

And don’t go wrong as well they might.

Such pleasures don’t endure, so bite

The grapes of fortune to the pip.

How rare it is when things go right

And don’t go wrong as well they might.

The villanelle is the reason I am writing this book. Not that lame example, but the existence of the form itself.

Let me tell you how it happened. I was in conversation with a friend of mine about six months ago and the talk turned to poetry. I commented on the extraordinary resilience and power of ancient forms, citing the villanelle.

10

‘What’s a villanelle?’

‘Well, it’s a pastoral Italian form from the sixteenth century written in six three-line stanzas where the first line of the first stanza is used as a refrain to end the second and fourth stanzas and the last line of the first stanza is repeated as the last line of the third, fifth and sixth,’ I replied with fluent ease.

You have never heard such a snort of derision in your life.

‘

What

? You have

got

to be kidding!’

I retreated into a resentful silence, wrapped in my own thoughts, while this friend ranted on about the constraint and absurdity of writing modern poetry in a form dictated by some medieval Italian shepherd. Inspiration suddenly hit me. I vaguely remembered that I had once heard this friend express great admiration for a certain poet.

‘Who’s your favourite twentieth-century poet?’ I asked nonchalantly.

Many were mentioned. Yeats, Eliot, Larkin, Hughes, Heaney, Dylan Thomas.

‘And your favourite Dylan Thomas poem?’

‘It’s called “Do not go gentle into that good night”.’

‘Ah,’ I said. ‘Does it have any, er, what you might call

form

particularly? Does it rhyme, for instance?’

He scratched his head. ‘Well, yeah it does rhyme I think. “Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” and all that. But it’s like–modern. You know, Dylan Thomas.

Modern

. No crap about it.’

‘Would you be surprised to know’, I said, trying to keep a note of ringing triumph from my voice, ‘that “Do not go gentle into that good night” is a straight-down-the-line, solid gold, one hundred per cent perfect, unadulterated

villanelle

?’

‘Bollocks!’ he said. ‘It’s modern. It’s free.’

The argument was not settled until we had found a copy of the poem and my friend had been forced to concede that I was right. ‘Do not go gentle into that good night’ is indeed a perfect villanelle, following all the rules of this venerable form with the greatest precision. That my friend could recall it only as a ‘modern’ poem with a couple of memorable rhyming refrains is a testament both to Thomas’s unforced artistry and to the resilience and adaptability of the form itself: six three-line stanzas or

tercets

,

11

each alternating the refrains introduced in the first stanza and concluding with them in couplet form:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright

Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight,

And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way,

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight

Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay,

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

The conventional way to render the villanelle’s plan is to call the first refrain (‘Do not go gentle’) A1 and the second refrain (‘Rage, rage…’)A2. These two rhyme with each other (which is why they share the letter): the second line (‘Old age should burn’) establishes the

b

rhyme which is kept up in the middle line of every stanza.

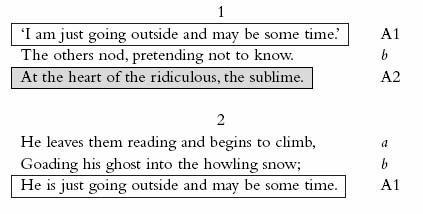

Much easier to grasp in action than in code. I have boxed and shaded the refrains here in Derek Mahon’s villanelle ‘Antarctica’. (I have also numbered the line and stanzas, which of course Mahon did not do):

3