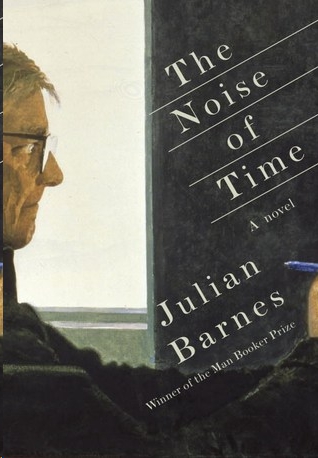

The Noise of Time

Authors: Julian Barnes

Tags: #Contemporary Fiction, #Contemporary, #Literature & Fiction, #Literary

The Noise of Time

Julian Barnes

Vintage Digital (2016)

Rating: ★★★★☆

Tags: Literature & Fiction, Contemporary, Literary, Contemporary Fiction

Literature & Fictionttt Contemporaryttt Literaryttt Contemporary Fictionttt

'BARNES'S MASTERPIECE.' - *OBSERVER

*

In May 1937 a man in his early thirties waits by the lift of a Leningrad apartment block. He waits all through the night, expecting to be taken away to the Big House. Any celebrity he has known in the previous decade is no use to him now. And few who are taken to the Big House ever return.

So begins Julian Barnes’s first novel since his Booker-winning

The Sense of an Ending

. A story about the collision of Art and Power, about human compromise, human cowardice and human courage, it is the work of a true master.

**

Contents

About the Book

In May 1937 a man in his early thirties waits by the lift of a Leningrad apartment block. He waits all through the night, expecting to be taken away to the Big House. Any celebrity he has known in the previous decade is no use to him now. And few who are taken to the Big House ever return.

So begins Julian Barnes’s first novel since his Booker-winning

The Sense of an Ending

. A story about the collision of Art and Power, about human compromise, human cowardice and human courage, it is the work of a true master.

About the Author

Julian Barnes is the author of twelve novels, including

The Sense of an Ending

, which won the 2011 Man Booker Prize for Fiction. He has also written three books of short stories,

Cross Channel, The Lemon Table

and

Pulse

; four collections of essays; and two books of non-fiction,

Nothing to be Frightened Of

and the

Sunday Times

Number One bestseller

Levels of Life

. He lives in London.

Also by Julian Barnes

FICTION

Metroland

Before She Met Me

Flaubert’s Parrot

Staring at the Sun

A History of the World in 10½ Chapters

Talking it Over

The Porcupine

Cross Channel

England, England

Love, etc

The Lemon Table

Arthur & George

Pulse

The Sense of an Ending

NON-FICTION

Letters from London 1990–1995

Something to Declare

The Pedant in the Kitchen

Nothing to be Frightened of

Through the Window

Levels of Life

Keeping an Eye Open

TRANSLATION

In the Land of Pain

by Alphonse Daudet

for Pat

The Noise of Time

Julian Barnes

One to hear

One to remember

And one to drink.

traditional

It happened in the middle of wartime, on a station platform as flat and dusty as the endless plain surrounding it. The idling train was two days out from Moscow, heading west; another two or three to go, depending on coal and troop movements. It was shortly after dawn, but the man – in reality, only half a man – was already propelling himself towards the soft carriages on a low trolley with wooden wheels. There was no way of steering it except to wrench at the contraption’s front edge; and to stop himself from overbalancing, a rope that passed underneath the trolley was looped through the top of his trousers. The man’s hands were bound with blackened strips of cloth, and his skin hardened from begging on streets and stations.

His father had been a survivor of the previous war. Blessed by the village priest, he had set off to fight for his homeland and the Tsar. By the time he returned, priest and Tsar were gone, and his homeland was not the same. His wife had screamed when she saw what war had done to her husband. Now there was another war, and the same invader was back, except that the names had changed: names on both sides. But nothing else had changed: young men were still blown to bits by guns, then roughly sliced by surgeons. His own legs had been removed in a field hospital among broken trees. It was all in a great cause, as it had been the time before. He did not give a fuck. Let others argue about that; his only concern was to get to the end of each day. He had become a technique for survival. Below a certain point, that was what all men became: techniques for survival.

A few passengers had descended to take the dusty air; others had their faces at the carriage windows. As the beggar approached, he would start roaring out a filthy barrack-room song. Some passengers might toss him a kopeck or two for the entertainment; others pay him to move on. Some deliberately threw coins to land on their edge and roll away, and would laugh as he chased after them, his fists working against the concrete platform. This might make others, out of pity or shame, hand over money more directly. He saw only fingers, coins and coat-sleeves, and was impervious to insult. This was the one who drank.

The two men travelling in soft class were at a window, trying to guess where they were and how long they might be stopping for: minutes, hours, perhaps the whole day. No information was given out, and they knew not to ask. Enquiring about the movement of trains – even if you were a passenger on one – could mark you as a saboteur. The men were in their thirties, well old enough to have learnt such lessons. The one who heard was a thin, nervous fellow with spectacles; around his neck and wrists he wore amulets of garlic. His travelling companion’s name is lost to history, even though he was the one who remembered.

The trolley with the half-man aboard now rattled towards them. Cheerful lines about some village rape were bellowed up at them. The singer paused and made the eating sign. In reply, the man with spectacles held up a bottle of vodka. It was a needless gesture of politeness. When had a beggar ever turned down vodka? A minute later, the two passengers joined him on the platform.

And so there were three of them, the traditional vodka-drinking number. The one with spectacles still had the bottle, his companion three glasses. These were filled approximately, and the two travellers bent from the waist and uttered the routine toast to health. As they clinked glasses, the nervous fellow put his head on one side – the early-morning sun flashing briefly on his spectacles – and murmured a remark; his friend laughed. Then they threw the vodka down in one go. The beggar held up his glass for more. They gave him another shot, took the glass from him, and climbed back on the train. Thankful for the burst of alcohol coursing through his truncated body, the beggar wheeled himself towards the next group of passengers. By the time the two men were in their seats again, the one who heard had almost forgotten what he had said. But the one who remembered was only at the start of his remembering.

One: On the Landing

ALL HE KNEW

was that this was the worst time.

He had been standing by the lift for three hours. He was on his fifth cigarette, and his mind was skittering.

Faces, names, memories. Cut peat weighing down his hand. Swedish water birds flickering above his head. Fields of sunflowers. The smell of carnation oil. The warm, sweet smell of Nita coming off the tennis court. Sweat oozing from a widow’s peak. Faces, names.

The faces and names of the dead, too.

He could have brought a chair from the apartment. But his nerves would in any case have kept him upright. And it would look decidedly eccentric, sitting down to wait for the lift.

His situation had come out of the blue, and yet it was perfectly logical. Like the rest of life. Like sexual desire, for instance. That came out of the blue, and yet it was perfectly logical.

He tried to keep his mind on Nita, but his mind disobeyed. It was like a bluebottle, noisy and promiscuous. It landed on Tanya, of course. But then off it buzzed to that girl, that Rozaliya. Did he blush to remember her, or was he secretly proud of that perverse incident?

The Marshal’s patronage – that had also come out of the blue, and yet it was perfectly logical. Could the same be said of the Marshal’s fate?

Jurgensen’s affable, bearded face; and with it, the memory of his mother’s fierce, angry fingers around his wrist. And his father, his sweet-natured, lovable, impractical father, standing by the piano and singing ‘The Chrysanthemums in the Garden Have Long Since Faded’.

The cacophony of sounds in his head. His father’s voice, the waltzes and polkas he had played while courting Nita, four blasts of a factory siren in F sharp, dogs outbarking an insecure bassoonist, a riot of percussion and brass beneath a steel-lined government box.

These noises were interrupted by one from the real world: the sudden whirr and growl of the lift’s machinery. Now it was his foot that skittered, knocking over the little case that rested against his calf. He waited, suddenly empty of memory, filled only with fear. Then the lift stopped at a lower floor, and his faculties re-engaged. He picked up his case and felt the contents softly shift. Which made his mind jump to the story of Prokofiev’s pyjamas.

No, not like a bluebottle. More like one of those mosquitoes in Anapa. Landing anywhere, drawing blood.

He had thought, standing here, that he would be in charge of his mind. But at night, alone, it seemed that his mind was in charge of him. Well, there is no escaping one’s destiny, as the poet assured us. And no escaping one’s mind.

He remembered the pain that night before they took his appendix out. Throwing up twenty-two times, swearing all the swear-words he knew at a nurse, then begging a friend to fetch the militiaman to shoot him and end the pain. Get him to come in and shoot me to end the pain, he had pleaded. But the friend had refused to help.

He didn’t need a friend and a militiaman now. There were enough volunteers already.

It had all begun, very precisely, he told his mind, on the morning of the 28th of January 1936, at Arkhangelsk railway station. No, his mind responded, nothing begins just like that, on a certain date at a certain place. It all began in many places, and at many times, some even before you were born, in foreign countries, and in the minds of others.

And afterwards, whatever might happen next, it would all continue in the same way, in other places, and in the minds of others.

He thought of cigarettes: packs of Kazbek, Belomor, Herzegovina Flor. Of a man crumbling the tobacco from half a dozen papirosy into his pipe, leaving on the desk a debris of cardboard tubes and paper.

Could it, even at this late stage, be mended, put back, reversed? He knew the answer: what the doctor said about the restoration of The Nose. ‘Of course it can be put back, but I assure you, you will be the worse for it.’

He thought about Zakrevsky, and the Big House, and who might have replaced Zakrevsky there. Someone would have done. There was never a shortage of Zakrevskys, not in this world, constituted as it was. Perhaps when Paradise was achieved, in almost exactly 200,000,000,000 years’ time, the Zakrevskys would no longer need to exist.

At moments his mind refused to believe what was happening. It can’t be, because it couldn’t ever be, as the Major said when he saw the giraffe. But it could be, and it was.

Destiny. It was just a grand term for something you could do nothing about. When life said to you, ‘And so,’ you nodded, and called it destiny. And so, it had been his destiny to be called Dmitri Dmitrievich. There was nothing to be done about that. Naturally, he didn’t remember his own christening, but had no reason to doubt the truth of the story. The family had all assembled in his father’s study around a portable font. The priest arrived, and asked his parents what name they intended for the newborn. Yaroslav, they had replied. Yaroslav? The priest was not happy with this. He said that it was a most unusual name. He said that children with unusual names were teased and mocked at school: no, no, they couldn’t call the boy Yaroslav. His father and mother were perplexed by such forthright opposition, but didn’t wish to give offence. What name do you suggest then? they asked. Call him something ordinary, said the priest: Dmitri, for instance. His father pointed out that he himself was already called Dmitri, and that Yaroslav Dmitrievich sounded much better than Dmitri Dmitrievich. But the priest did not agree. And so he became Dmitri Dmitrievich.