The New Middle East

Read The New Middle East Online

Authors: Paul Danahar

For Bhavna

Optimus est post malum principem dies primus.

The best day after a bad emperor is the first one.

TACITUS

Contents

1 The Collapse of the Old Middle East

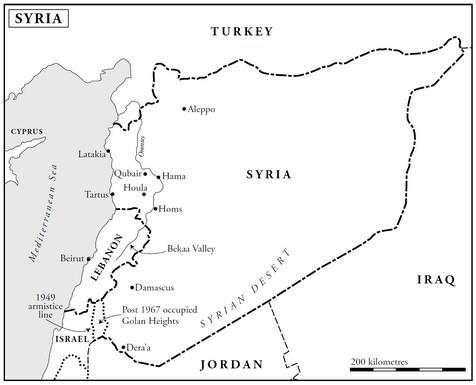

8 Syria: The Arab World’s Broken Heart

‘Even if you win, it is difficult to rule an angry people,’ he told me. The world was glued to the crisis in Syria, but as we sat sipping coffee in the Foreign Ministry in Damascus in June of 2012, Jihad Makdissi had an old Jackie Chan film playing on the TV. In the movie the bad guys were getting a beating for troubling one of the nice families in the neighbourhood. In the real world it was the nice families who were getting the beating at the interrogation centres set up by Makdissi’s colleagues. His country, the crossroads of the region, the ‘beating heart’ of the Arab world, was sliding into civil war. Makdissi was the very public face of the regime, answering its critics on TV screens across the world. But he and the other civilian members of the regime were not only scared of the opposition groups creeping closer to the capital. They feared the scrutiny of their own increasingly predatory security services.

The certainties of the old Middle East, the world Jihad Makdissi had always belonged to, were crumbling around him.

Just down the road the men in blue helmets were watching their mission spiral away from them. ‘This is a YouTube war,’ said the diplomat from the United Nations, leaning towards me, his voice low and throttled with anger. He pulled on his cigarette and sat back in his chair. We were in the bubble of their headquarters. This man

was

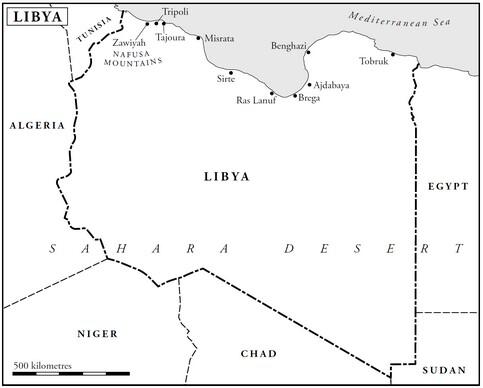

watching the news, constantly. It was dominated by images uploaded by tech-savvy teenagers armed with a video camera and a broadband line. His boss, the man leading the United Nations’ peacekeeping mission in Syria, Major General Robert Mood, told me at the time that these images had driven much of the reaction in the West to the crisis. But as the war entered its third year he remembered the moment he told the youngsters it wouldn’t be enough. ‘ “We saw Libya, when do you think they are coming?” they asked me. You could see the disappointment in their eyes when I said: “Honestly I don’t think you can expect that in Syria.” ’

The UN was there to be a neutral pair of eyes, but the nature of the war meant it was often impossible to determine the truth. The previous day I had gone out with their ‘ceasefire’ monitors and ended up standing on a roof alongside them watching the Syrian army lob mortar rounds into a residential district of the city of Homs. The Syrian government had welcomed the UN into the country but now wouldn’t let them into the area to see whom their army was bombarding. It was the last time the observers would try to enter, because five days later the worsening violence forced the UN to suspend all its patrols. The following month the number of killings in Syria began to soar.

1

‘This is a fight between Russia on one side with the Iranians, and the whole Western world. The Americans are now on the same side as al-Qaeda!’ said the exasperated diplomat. Neither of us knew it then, but the man first charged with finding a peaceful solution to the conflict had also reached the end of his tether. Kofi Annan, the joint United Nations and Arab League envoy, would soon be resigning from his ‘Mission Impossible’ with a scathing attack on the ‘finger-pointing and name-calling’ between the members of the Security Council.

2

By the time I returned to Damascus in February 2013 the UN had said almost seventy thousand people had died in the conflict.

3

Jihad Makdissi had fled the country. As the year wore on the death toll kept climbing.

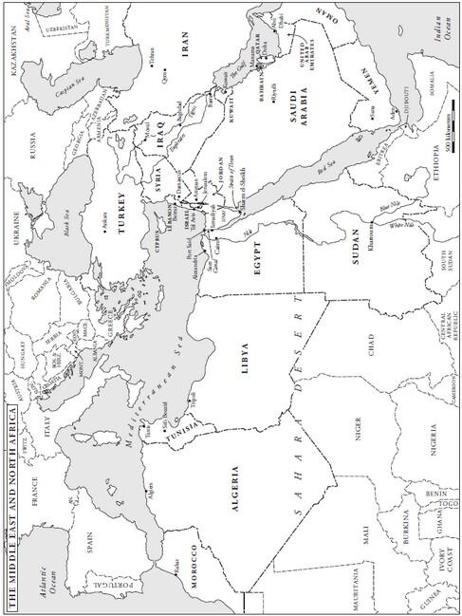

Nothing expressed the profound shock caused by the collapse of the old order in the Middle East more clearly than the confused and dithering reaction of the outside world to the war in Syria. It simply did not know what to do. The only Great Power, America, used to have a simple solution for problems in the region: ring the Israelis or ring the Egyptians or ring the Saudis. Or ring all three and let them get on with it. That easy set of instructions has been consumed by the political inferno that has raged through the region in the wake of the first Arab uprising in Tunisia. The telephone numbers may have stayed the same but the people at the other end, and their priorities, have not. Newly influential players have emerged. Writing the next rulebook has barely begun. Barbara Bodine, the former US ambassador to Yemen, told me: ‘I really don’t know anybody who liked dealing with dictators, but there is a perverse simplicity to it.’ The world after the Arab Spring is now much more complex.

The old Middle East stopped making sense years ago. The Soviet Union had been dead for decades. One by one, around the world, in Africa, South America and in Eastern Europe, brutal regimes had fallen, or been abandoned by their foreign sponsors. Elsewhere, for better or worse, the world had moved on – but not here. In the old Middle East the unholy alliance between ‘the Land of the Free’ and the world of dictatorship limped on because no one knew what else to do. It took schoolteachers, farmers and accountants to achieve what generations of diplomats and world leaders failed to do. The creation of a New Middle East. But revolution is only the journey; it does not bring you to a destination. It is a process, not a result. We can see now that this journey is leaving behind the old socialist ideologies of Ba’athism and Pan-Arabism, and those carried by the founders of Zionism. There is a stronger Sunni, and a weaker Shia, Islam. There is a growing religious divide in Israel. The regional powers are now more strongly divided along sectarian lines. Christians and other minorities wonder if they still have a safe place in the new societies being formed. Religion, not nationalism or Arabism, is now the dominant force.