The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (38 page)

Read The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

These were the two adversaries who, in 1871, found themselves locked in a cutthroat battle to control the Red River traffic between Minnesota and Fort Garry, where the nearby village of Winnipeg was slowly rising out of the prairie mud. Since it was axiomatic that neither would give quarter to the other, the two at last agreed to join forces in secret. On the face of it, both the Hudson’s Bay Company and Jim Hill retired from the steamboat business and left the trade in the hands of Norman Kittson’s Red River Transportation Company. In actual fact, the Kittson Line, as it was called, was a joint venture of Hill, Kittson and the Hudson’s Bay Company. The company’s shares were in Smith’s name, but he agreed in advance to transfer them to whoever succeeded him as chief commissioner. The Kittson Line gave the Hudson’s Bay Company a one-third discount on all river freight, and thus a commanding edge on its competitors. That, too, was part of the secret.

No sooner was this clandestine arrangement completed than the freight rates shot skyward. In the winter of 1874–75 a group of Winnipeg and Minnesota merchants, incensed at the monopoly, launched a steamboat line of their own – the Merchants’ International. They built two large steamboats, the

Minnesota

and the

Manitoba

, and when the first of these, the

Manitoba

, steamed into Winnipeg on Friday morning, May 14, 1875, an impromptu saturnalia took place on her decks. Champagne flowed all that day, all that night and again the following morning by which time the merrymakers had broken a fair share of the vessel’s glass and crockery and thrown all their hats overboard in celebration of their release from “the dreaded monopoly.”

That summer there were seven stern-wheelers plying the Red and another battle was in progress. Norman Kittson, who had once fought the Hudson’s Bay as a free trader in Pembina, now fought on the Company’s side and without giving quarter. He launched a rate war, bringing his own prices down below cost. Through friends in the Pembina customs depot, he arranged that the

Manitoba

be held indefinitely at the border. When it was finally released in July, Kittson charged it broadside with his

International

, rammed it and sank it with its entire cargo. The Merchants’ Line raised the battered craft

and repaired it at staggering cost. No sooner was it back in service than it was seized for a trifling debt. The same fate awaited its sister ship, south of the border. Reeling from this series of blows, the merchants sold out to Kittson in September. Up went the rates again, as Kittson and his colleagues shared a dividend of eighty per cent and the rising wrath of the Red River community. The tousled John Christian Schultz, Conservative member for Lisgar, Manitoba – he had been Riel’s prisoner and leading opponent in 1871 – claimed that wheat could be sent the whole length of the Mississippi for half the cost of the three hundred miles of slack water covered by Kittson’s steamboats.

There was good reason for this fevered strife. The trickle of newcomers into the Red River Valley was rapidly becoming a torrent. They arrived, in Schultz’s words, “huddled like sheep and treated like hogs in the lower decks” of the “notorious monopoly.” By the mid-seventies, the immigrant sheds on the banks of the Red near its confluence with the Assiniboine were bursting with new arrivals who spilled out into a periphery of scattered tents and board shacks. Obviously, whoever controlled transportation into the newly incorporated town of Winnipeg would reap rich profits.

At the time of its incorporation in 1873, Winnipeg was still, in George Ham’s description, “a muddy, disreputable village,” sprawled between Main Street and the river. It had no sidewalks, no waterworks, no sewerage, no pavement; but it had gumbo of such a glutinous consistency that for more than a decade every traveller who described the town devoted several vituperative sentences to it. “It is a mud which no person who has not seen it can appreciate,” wrote one English parliamentarian. “A mixture of putty and bird-lime would perhaps most nearly describe it.” Baked hard by the sun it looked innocent enough; but the first rainstorm turned it into a tenacious adhesive which clung stubbornly to boots and clothes and made foot travel a nightmare. Only the most perceptive of the old timers saw that the mud was wealth. Father Lacombe, the itinerant prairie Oblate, once happened upon a party of immigrants so totally discouraged by Winnipeg’s mud that they were planning to return to the East. Lacombe gave them a tongue-lashing: “Then go back, since you have not any more sense than to judge a country before you have looked into it. If there is deep mud here it is only because the soil is fat – the richest in America. But go back to your Massachusetts, if you want, where the soil is all pebbles, and work again in the factories.”

Though the mud was not easily conquered, small signs of progress began to appear as the community grew. The first ornamental street lamp was installed in 1873. The following January there appeared in the streets a covered wagon from Minnesota, heated by a stove and advertising “California fruits and other delicacies.” An improved “house to house water service” was started by George Rath – a tank on four wheels, drawn by oxen, complete with pump and forty feet of hose “by which means the water can be introduced into the houses of our citizens without the pail system.” And in September 1874, the first sod was turned on the long-awaited railway that was to run from Selkirk through neighbouring St. Boniface to Pembina, to connect, it was hoped, at the border with a United States line, as yet uncompleted.

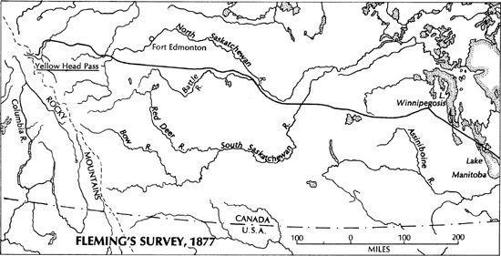

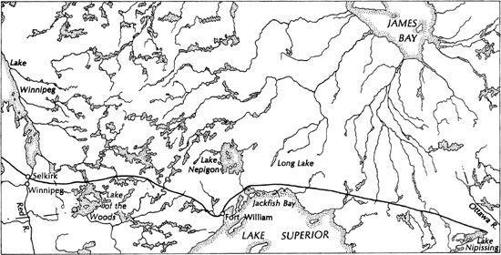

Winnipeg had already outdistanced the old Hudson’s Bay post of Fort Garry in size but, to its growing chagrin, it was not on the main line of the

CPR

. The route being planned from the head of Lake Superior was to go through Selkirk some twenty miles to the northeast. After that, it was intended that it should swing sharply north and across the pinched midriff of Lake Manitoba at The Narrows before following the general line of the Fertile Belt to Edmonton. Under this scheme of things the road would ignore the two major settlements in the new Manitoba – Winnipeg and Portage la Prairie. In spite of the obvious political inexpediency of such a route, Sandford Fleming continued to cling to it, to the repeated howls of the Winnipeggers. “A tough subject with an election at hand,” Marcus Smith wrote to Fleming late in 1877. “I fear politics will be a more powerful consideration than reason.” A month later he advised Fleming to tone down his condemnation of a proposed deviation, which would take the railroad south of the lake, and suggested that the whole matter be postponed until after the 1878 election by the old device of resurveying. “The result of the survey,” Smith concluded, “will probably be to keep the present line.”

The pull of population would soon outweigh engineering considerations and Winnipeg would eventually force a change in the main line. By 1877, southern Manitoba had become, in the words of one government pamphlet, “the most inviting field for immigration in the world.” In the early days there had been only one hotel in Winnipeg but by the mid decade rival after rival was springing up: the Grand Central, the International, and then the Merchants’ and finally the Queen’s, the most ostentatious caravanserai in the North West. Rents were astronomical. A six-room house could not be had for less than fifty dollars a month – four or five times as much as a similar dwelling in Toronto. In 1876, Walter Moberly and his former surveying colleague Roderick McLennan built the first wooden sewer down Main Street – the first, indeed, in all the North West. Another ex-surveyor, Edward Jarvis, the man who had almost starved to death the previous year exploring the Smoky River Pass, was doing a roaring business in lumber and starving no more. Winnipeg could no longer be ignored.

The construction of the Pembina Branch proceeded at an unbelievably leaden pace. After the grading was completed work stopped. There was, after all, no point in building a railroad to nowhere – and there was as yet no connecting American line to be seen on the horizon. The contract for laying steel was not let for another three years until it became clear that the moribund St. Paul and Pacific, reorganized and renamed the St. Paul and Manitoba, was actually going to reach the border (as it did late in 1878).

The last spike in the Pembina Branch was finally driven in November, 1878. By this time the population of Winnipeg had risen to six thousand and a gala excursion load of citizens was taken by train to Rousseau for the ceremony. Here a gap, 125 yards long, still lay incomplete. Two teams of workers set about finishing the line, cheered on by the gleeful throng. It was decided that one of the ladies should have the honour of driving the final spike, but no one could decide which one. Finally, the silver-haired United States consul, James Wiekes Taylor, who had, ironically, worked secretly for years for the annexation of the Canadian North West by Jay Cooke and his forces, made the diplomatic suggestion that

all

the ladies present should be allowed a whack. Each in her turn hammered away, with little success, until Taylor called over Mary Sullivan, the strapping daughter of an Irish section boss. With a single blow, the buxom Miss Sullivan drove the spike home, to the cheers of the assembly.

The cheers did not last long. The rails had been laid, but to describe the Pembina Branch as a railway was to indulge in the wildest kind of hyperbole. Under the terms of the contract, the builders had until November 1879 to complete the job and turn the finished line over to the government. They determined, in the meantime, to squeeze the maximum possible profit out of it by running it themselves while they continued to build the necessary sidings, station houses, water towers and all the requisite paraphernalia that is part of a properly run railway.

In the months that followed, the Pembina line became the most

cursed length of track on the continent. Since there was only one water tank on the whole sixty-three miles, it was the practice of the engineer, when his boiler ran out of steam, to halt beside the closest stream and replenish his water supply. There was no shred of telegraph line along the entire right of way and so the train dispatching had to be accomplished by using human runners. There were, of course, no repair shops nor were there any fences, which meant the train must make frequent stops to allow cattle to cross the tracks. The only fuel was green poplar, which was piled along the track at intervals. It gave off enormous and encouraging clouds of dense smoke but supplied little energy. Under such conditions it was not easy to build up a head of steam: the passengers were often compelled to wait at a station while the unmoving locomotive, wheezing and puffing away, finally gathered enough motive power to falter off to the next one. The trip to Winnipeg was best described – and in an understatement – as “leisurely.” Passengers were in the habit of alighting to watch the perspiring crew hurling poplar logs aboard the tender. Sometimes they would wander into the woods and go to sleep in the shade. On each of these stops it became necessary to make a head count and beat the bushes, literally, for missing ticket holders. An even more ludicrous spectacle was caused by the lack of a turntable at St. Boniface. When the engine reached that point, it could not turn about but had to make the entire trip back to the border tender foremost.

To travel the Pembina line in those days required nerves of steel, a stomach of iron and a spirit of high adventure. Each time a bridge was crossed, the entire structure, foundations and all, swayed and rocked in a dismaying fashion. The road was improperly ballasted so that even at eleven miles an hour, the cars pitched and tumbled about. In many places mud spurted over the tops of the sleepers. A man from

The Times

of London, surely accustomed to the derring-do of Victorian journalism, reported that he and his party were more seasick on the Pembina Branch than they had been crossing the stormy Atlantic. One of the company, so

The Times’s

man said, had not really said his prayers in a long, long time but was so shattered by the experience that he reformed on the spot, took to praying incessantly and, through sheer terror, managed to scare up some extra prayers that had lain forgotten in the dim recesses of his mind since childhood; the Pembina railroad shook them loose.