The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 (33 page)

Read The National Dream: The Great Railway, 1871-1881 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

But he was also “Edgar the Unlucky,” a nickname he was in the process of earning for a run of adversity at the polls: he lost five elections in a row. In Victoria, it was his misfortune to batter his head against the unyielding barrier of George Walkem’s intransigence. The two and a half months he spent in British Columbia must have been frustrating ones to Edgar. Walkem, the new premier, drove him into a state of helpless rage.

“Not, I imagine, a person of any great consequence,” wrote the lofty Lord Dufferin of De Cosmos’s successor. “He is a lawyer in a small village and the son of a clerk in the Dominion Militia Department, so that in one’s intercourse with him, one has to be on one’s guard against the intellectual frailties engendered by his professional antecedents.”

The man the Governor General thus dismissed was short of stature, robust of physique and – with his eyeglasses, drooping moustache and thin, wispy cowlick – Kiplingesque of feature. He may have suffered from intellectual frailties, but there was a streak of brilliance in his family and a broad stripe of political shrewdness in his make-up. All of his brothers – he came from a family of ten – had achieved

professional success: a distinguished judge, a master in chancery, an actuary, a British army officer, a physician, a journalist. As a long-time lawyer in the Cariboo gold-fields, Walkem knew how to assume a rough-and-ready front; he was a hard drinker, an amusing raconteur and a brother-in-arms to the placer miners. He was also an artist in crayons; his pictures won prizes in provincial exhibitions. He had a propensity for drawing lions, a diversion that attracted little notice in those pre-Freudian times.

When Walkem replaced De Cosmos, he jumped with both boots into the heated Battle of the Routes, which was to occupy the entire decade. It was clear from the way the surveys were proceeding that in spite of the previous year’s sod-turning ceremony, the engineers had not made up their minds about the location of the

CPR

terminus. Not a single dollar had been spent on the railway to Nanaimo; while on the mainland, merchants like David Oppenheimer of Kamloops (a future mayor of Vancouver) were doing a roaring business selling supplies to survey crews. The intense regional jealousy that marked relations between island and mainland was prolonged and refueled by the railway question as other local antipathies would be. Edmonton versus Calgary, Regina versus Moose Jaw, Fort William versus Port Arthur – these all had their beginnings in the days when the terminus of the railway or the choice of a divisional point or the location of a station could mean dollars in the pockets of merchants, professionals and, above all, real estate speculators.

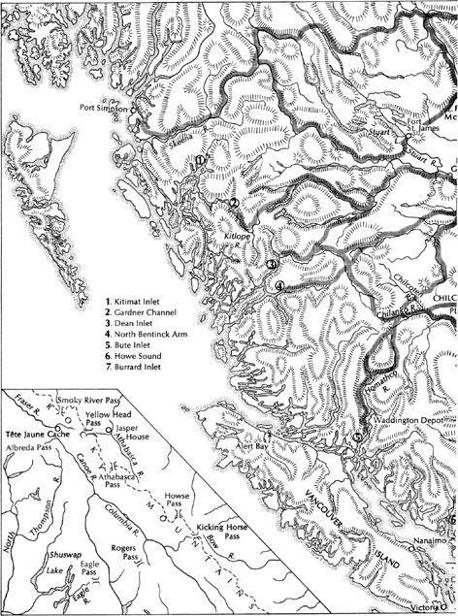

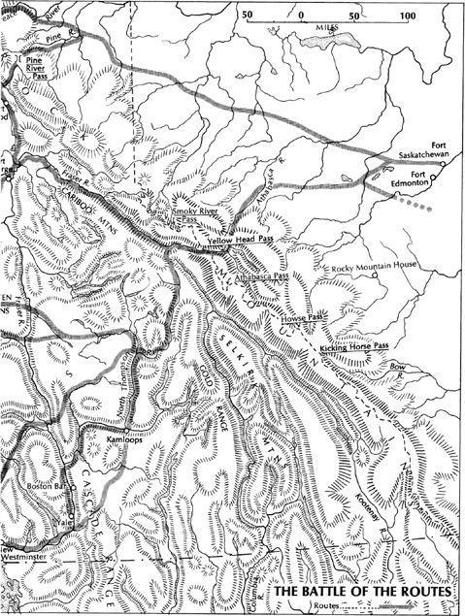

In British Columbia, Vancouver Island lined up against the mainland in a struggle that was not to end until 1880. At the close of 1873, Sandford Fleming was considering seven alternate routes to the coast. Two of these had their terminus at Burrard Inlet, three at Bute Inlet, one at Howe Sound and one at North Bentinck Arm. Later on other possibilities arose: Dean Inlet, Gardner Channel, Port Simpson and the mouth of the Kitlope. No fewer than six passes in the Rockies were being explored. By mid-decade Fleming was able to report on twelve different routes through British Columbia to seven different harbours on the coastline.

But as far as British Columbia was concerned, there were only two routes that really mattered. One was the ancient trail used by the fur traders and explorers through the Yellow Head Pass and down the Fraser canyon to Burrard Inlet; if chosen it would guarantee the prosperity of Kamloops, Yale, New Westminster and all the valley points between. This was the route the mainland fought for. The

other would lead probably from the Yellow Head Pass through the Cariboo country and the Chilcoten plains to the Homathco River and Bute Inlet, then leap the straits to Nanaimo and thence to Victoria; it would guarantee the prosperity of the dying gold region and the island. Walkem, a Cariboo man who knew a political issue when he saw one, opted instinctively for the Bute Inlet route.

From March 9 to May 18, 1874, Edgar did his best to negotiate with Walkem: the government could not build the railway immediately but it would prosecute the surveys energetically; it would spend an annual million and a half dollars on railway construction in the province, once the surveys were completed; and, in the meantime, it was prepared to build a wagon road and telegraph line across British Columbia. Early in April, Edgar added a sweetener: the government was also prepared to commence at once the construction of a line from Esquimalt to Nanaimo.

This pleased nobody. The islanders suspected a plot to make their line a purely local one. What was to prevent the government from scrapping both the Bute route and the causeway across the straits? The jealous mainlanders, on the other hand, felt the island was being outrageously favoured. In April, Edgar reported that “it was now quite apparent that the Local Ministers were determined to be obstructive.” In May, Walkem wriggled out of the entire matter by calling Edgar’s credentials into question. What authority did he have, anyway, to act as a government agent? The exasperated Edgar expostulated that Walkem and his colleagues had “recognized me as such agent almost every day for two months.” It did no good. Walkem blandly stuck to his point that he had no proof that Edgar was specially accredited. This “extraordinary treatment” sent Edgar back to the East in a huff.

With Edgar thus disposed of, Walkem meant to go over Mackenzie’s head to the Crown itself. He prepared to set off, memorial in hand, to see Lord Carnarvon, the delicate-featured colonial secretary, whom Disraeli called “Twitters,” because he had difficulty coming to a decision. In this instance, Carnarvon was uncharacteristically expeditious. Briefed in advance by British Columbia’s agent-general in London, he did not bother to wait for Walkem. He telegraphed to Ottawa on June 17 that he was prepared personally to arbitrate the dispute between British Columbia and the Canadian government.

The time was not far off when the very whisper of the Colonial Office interfering in the domestic affairs of an independent dominion

would raise the hackles of the least sensitive of politicians. Certainly Mackenzie’s immediate instinct was to reject the offer. He telegraphed a rebuff of “the curtest description,” in Carnarvon’s pained phrase. Dufferin, who was on a fishing trip at the time, after being “cooped up for nine consecutive months,” apologized for the stonemason’s characteristic bluntness; had he been in Ottawa, he hastened to assure Carnarvon, his first minister’s reply “would have been couched in different terms.”

These ruffled feelings were scarcely soothed when Walkem appeared on the horizon, like Cogeia’s comet, which was that month clearly visible in the sky. He saw Mackenzie and there was a cursory attempt to reach an agreement. When the Prime Minister asked Walkem to put his proposals on paper, the British Columbia premier replied with “a very hostile memorandum,” and that was that. Walkem steamed off to London where Carnarvon, briefed by his prolific vice-regal correspondent in Ottawa regarding the Premier’s “intellectual frailties,” saw him in early August and renewed his offer of arbitration.

“I am having a terrible fight with my government,” Dufferin informed him a month later. The Governor General wanted Mackenzie to accept Carnarvon’s offer but he was meeting resistance. In Parliament, the Prime Minister’s supporters were blaming him because the Edgar offer was too liberal. Dufferin, who liked to have a finger in every political pie, kept on with his terrible fight. In all the long negotiations with British Columbia over the railway one gets the impression that Dufferin, in spite of his protests, his letters of exasperation (“People lie so much in this country,” he complained in July) and his knockdown battles with his ministry, was enjoying himself hugely. He was a dynamic and positive man, a veteran of twenty years of public service. He had been under-secretary for India and under-secretary for war in the Conservative cabinet. Now he had a role which certainly flattered his social position (though he would have much preferred to have been Viceroy of India) but frustrated his desire for direct action. A governor general had a little more leeway in those days than in later years and Dufferin took all the leeway he was allowed to – more than any other vice-regal appointee; but when it came to decision-making, he could only advise, he could not command.

In the end, the harassed Mackenzie, to his later regret, gave in and with the greatest reluctance accepted Lord Carnarvon’s offer of

arbitration. “From what I hear,” Lord Dufferin wrote, “Mr. Walkem will make no difficulties, and will hurry back to British Columbia across the bridge of gold we have built for him with the greatest expedition.” The “Carnarvon Terms,” which were to become a rallying cry in British Columbia, were remarkably similar to those proposed by Edgar: the island line would be built, the surveys would be pushed, and when the

CPR

began the government promised to spend at least two millions a year on its construction. In return, the province accepted an extension of the deadline to December 31, 1890.

Now the stoic stonemason, who had forborne to cry out under physical pressure, began to suffer under the crushing millstone of office. He was plagued with intestinal inflammation and insomnia, both the products of political tensions. “I am being driven mad with work – contractors, deputations and so on,” he told Edgar early in 1874. “Last night I was in my office until I was so used up I was unable to sleep.” A year later he was still driving himself: “The machine won’t stop … I’ll drive it whatever may betide if it should cost me my life.…” By 1876 the crunch of office caused him to cry out in a letter to Luther Holton about “a burden of care, the terrible weight of which presses me to the earth.” The railway – the terrible railway – a dream not of his invention, a nightmare by now, threatened to be his undoing. On one side he felt the pull of the upstart province on the Pacific, holding him to another man’s bargain – a bargain which his honour told him he must make an honest stab at fulfilling. On the other, he felt the tug of the implacable Blake, the rallying point for the anti-British Columbia sentiment and a popular alternative as Prime Minister.

Among the flaming maples of Aurora, north of Toronto, that October of 1874, the rebellious Blake, who had left the Cabinet on the eve of Edgar’s mission, delivered himself of the decade’s most discussed public speech. In a section devoted to railway policy he dismissed British Columbia as “a sea of mountains,” charged that it would cost thirty-six million dollars to blast a railway through it and declared the annual maintenance would be so costly that “I doubt much if that section can be kept open after it is built.”

He met the growing threats of separation from across the mountains head on: “If under all the circumstances, the Columbians should say – you must go on and finish this railway according to the terms or take the alternative of releasing us from the Confederation, I would take the alternative!”

That was exactly what the audience of hard-pressed farmers wanted to hear. They cheered him to the skies.

“They won’t secede,” Blake continued, sardonically. “They know better. Should they leave the Confederation, the Confederation would survive and they would lose their money.”

A ripple of laughter at the expense of the greedy British Columbians rolled up from the crowd. But on the far side of the divisive mountain rampart, the name of Blake became anathema – the symbol of the unfeeling East.

It was, of course, as illogical that Blake should be out of the Cabinet as it was dangerous; Mackenzie knew he must be lured back. Blake was willing but he had a price. A constitutional purist, he was totally incapable of the kind of political legerdemain which, in 1871, had caused a fictitious population explosion in British Columbia. In Aurora, he had made it clear that the Edgar proposals were the extreme limit; it was that or separation. But, under the Carnarvon Terms, the government was raising the stakes by an annual half million! This was too much; Mackenzie would have to backtrack. Mackenzie did: he added a hedge to the terms; they would be carried out

only

if that could be done without increasing taxes.