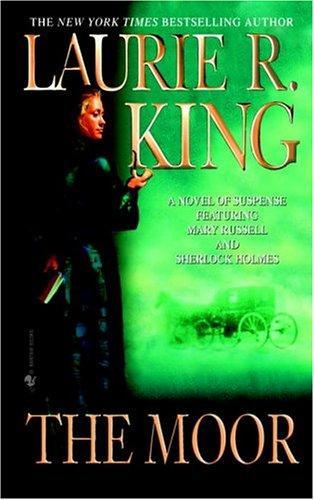

The Moor

Authors: Laurie R. King

________________________________

The Moor

by Laurie R. King

________________________________

Copyright © 1998 by Laurie R. King

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address St. Martin's Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

The Moor

A Peanut Press Book

Published by Peanut Press, LLC

www.peanutpress.com

ISBN: 0-312-20731-X

First Peanut Press Edition

Electronic format made

available by arrangement with

St. Martin's Press

The paper edition is

A Thomas Dunne Book.

An imprint of St. Martin's Press.

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Other Mystery Novels by Laurie R. King

Mary Russell Novels

A Letter of Mary

A Monstrous Regiment of Women

The Beekeeper's Apprentice

Kate Martinelli Novels

With Child

To Play the Fool

A Grave Talent

For Ruth Cavin,

editor extraordinaire,

with undying thanks and affection.

A blessing on you and your house.

WITH THANKS TO

Dr. Merriol Baring-Gould Almond and

the Reverend David Shacklock, for correcting as many of my missteps as I would allow

The Reverend Geoffrey Ball, rector of Lew Trenchard Church

Mr. Bill Crum, a mine of information

Ms. Kate De Groot, for bringing Brother Adam to my attention

Mr. Dave German and the other helpful shepherds of Princetown's High Moorland Visitor Information Centre

Mr. James and

Ms. Sue Murray, whose conversion of Lew House into Lewtrenchard Manor Hotel has been done with the same grace and warmth they show their visitors (and to

Holly and

Duma, who together do a very effective nocturnal imitation of the Hound)

Ms. Jo Pitesky, for the lost Russelism on page 28

Mr. David Scheiman (the real one), one of the good people

Ms. Mary Schnitzer, and to all of the readers.

They are not to be held responsible for any factual errors that may, either through misunderstanding or with malice afterthought, have stubbornly persisted into the final work. There are times, after all, when a writer must twist the truth in order to tell it.

EDITOR'S PREFACE

This is the fourth manuscript to be recovered from a trunk full of whatnot that was dropped on my doorstep some years ago. The various odds and ends—clothing, a pipe, bits of string, a few rocks, some old books, and one valuable necklace—might have been taken for some eccentric's grab bag or (but for the necklace) a clearing-out of attic rubbish intended for the dump, except that at the bottom lay the manuscripts.

I thought that they had been sent to me because the author was dead, and for some unknown reason chose to send me the memorabilia of her past. However, since the publication of the first Mary Russell book, I have received a handful of communications as ill assorted as the original contents of the trunk, and I have begun to suspect that the author herself is behind them.

***

It should be noted that in the course of her story, Ms. Russell tends to combine the actual names of people and places with other names that are unknown. Some of these thinly disguise true identities; others are impenetrable. Similarly, she seems to have taken some pains to conceal actual sites on the moor while at the same time referring to others, by name or description, that are easily identifiable. A walker on Dartmoor, therefore, will not find Baskerville Hall in the area given, and the characteristics of the Okemont River do not correspond precisely with those in the manuscript. I can only assume she did it deliberately, for her own purposes.

***

The chapter headings are taken from several of Sabine Baring-Gould's books, with the sources cited at each.

ONE

When I obtained a holiday from my books, I mounted my pony and made for the moor.

—A Book of Dartmoor

The telegram in my hand read:

RUSSELL NEED YOU IN DEVONSHIRE. IF FREE TAKE EARLIEST TRAIN CORYTON. IF NOT FREE COME ANYWAY. BRING COMPASS.

HOLMES

To say I was irritated would be an understatement. We had only just pulled ourselves from the mire of a difficult and emotionally draining case and now, less than a month later, with my mind firmly turned to the work awaiting me in this, my spiritual home, Oxford, my husband and longtime partner Sherlock Holmes proposed with this peremptory telegram to haul me away into his world once more. With an effort, I gave my landlady's housemaid a smile, told her there was no reply (Holmes had neglected to send the address for a response—no accident on his part), and shut the door. I refused to speculate on why he wanted me, what purpose a compass would serve, or indeed what he was doing in Devon at all, since when last I had heard he was setting off to look into an interesting little case of burglary from an impregnable vault in Berlin. I squelched all impulse to curiosity, and returned to my desk.

Two hours later the girl interrupted my reading again, with another flimsy envelope. This one read:

ALSO SIX INCH MAPS EXETER TAVISTOCK OKEHAMPTON. CLOSE YOUR BOOKS. LEAVE NOW.

HOLMES

Damn the man, he knew me far too well.

I found my heavy brass pocket compass in the back of a drawer. It had never been quite the same since being first cracked and then drenched in an aqueduct beneath Jerusalem some four years before, but it was an old friend and it seemed still to work reasonably well. I dropped it into a similarly well-travelled rucksack, packed on top of it a variety of clothing to cover the spectrum of possibilities that lay between arctic expedition and tiara-topped dinner with royalty (neither of which, admittedly, were beyond Holmes' reach), added the book on Judaism in mediaeval Spain that I had been reading, and went out to buy the requested stack of highly detailed six-inch-to-the-mile Ordnance Survey maps of the southwestern portion of England.

***

At Coryton, in Devon, many hours later, I found the station deserted and dusk fast closing in. I stood there with my rucksack over my shoulder, boots on feet, and hair in cap, listening to the train chuff away towards the next minuscule stop. An elderly married couple had also got off here, climbed laboriously into the sagging farm cart that awaited them, and been driven away. I was alone. It was raining. It was cold.

There was a certain inevitability to the situation, I reflected, and dropped my rucksack to the ground to remove my gloves, my waterproof, and a warmer hat. Straightening up, I happened to turn slightly and noticed a small, light-coloured square tacked up to the post by which I had walked. Had I not turned, or had it been half an hour darker, I should have missed it entirely.

Russell

it said on the front. Unfolded, it proved to be a torn-off scrap of paper on which I could just make out the words, in Holmes' writing:

Lew House is two miles north.

Do you know the words to "Onward Christian Soldiers" or "Widdecombe Fair"?

—H.

I dug back into the rucksack, this time for a torch. When I had confirmed that the words did indeed say what I had thought, I tucked the note away, excavated clear to the bottom of the rucksack for the compass to check which branch of the track fading into the murk was pointing north, and set out.

I hadn't the faintest idea what he meant by that note. I had heard the two songs, one a thumping hymn and the other one of those overly precious folk songs, but I did not know their words other than one song's decidedly ominous (to a Jew) introductory image of Christian soldiers marching behind their "cross of Jesus" and the other's endless and drearily jolly chorus of "Uncle Tom Cobbley and all." In the first place, when I took my infidel self into a Christian church it was not usually of the sort wherein such hymns were standard fare, and as for the second, well, thus far none of my friends had succumbed to the artsy allure of sandals, folk songs, and Morris dancing. I had not seen Holmes in nearly three weeks, and it did occur to me that perhaps in the interval my husband had lost his mind.

Two miles is no distance at all on a smooth road on a sunny morning, but in the wet and moonless dark in which I soon found myself, picking my way down a slick, rutted track, following the course of a small river which I could not see, but could hear, smell, and occasionally step in, two miles was a fair trek. And there was something else as well: I felt as if I were being followed, or watched. I am not normally of a nervous disposition, and when I have such feelings I tend to assume that they have some basis in reality, but I could hear nothing more solid than the rain and the wind, and when I stopped there were no echoing splashes of feet behind me. It was simply a sense of Presence in the night; I pushed on, trying to ignore it.

I stayed to the left when the track divided, and was grateful to find, when time came to cross the stream, that a bridge had been erected across it. Not that wading through the water would have made me much wetter, and admittedly it would have cleared my lower extremities of half a hundredweight of mud, but the bridge as a solid reminder of Civilisation in the form of county councils I found encouraging.

Having crossed the stream, I now left its burble behind me, exchanging the hiss of rain on water for the thicker noises of rain on mud and vegetation, and I was just telling myself that it couldn't be more than another half mile when I heard a faint thread of sound. Another hundred yards and I could hear it above the suck and plop of my boots; fifty more and I was on top of it.

It was a violin, playing a sweet, plaintive melody, light and slow and shot through with a profound and permanent sadness. I had never, to my knowledge, heard the tune before, although it had the bone-deep familiarity possessed by all things that are very old. I did, however, know the hands that wielded the bow.

"Holmes?" I said into the dark.

He finished the verse, drawing out the long final note, before he allowed the instrument to fall silent.

"Hello, Russell. You took your time."

"Holmes, I hope there is a good reason for this."

He did not answer, but I heard the familiar sounds of violin and bow being put into a case. The latches snapped, followed by the vigorous rustle of a waterproof being donned. I turned on the torch in time to see Holmes stepping out of the small shelter of a roofed gate set into a stone wall. He paused, looking thoughtfully at the telltale inundation of mud up my right side to the elbow, the result of a misstep into a pothole.

"Why did you not use the torch, coming up the road?" he asked.

"I, er…" I was embarrassed. "I thought there was someone following me. I didn't want to give him the advantage of a torch-light."

"Following you?" he said sharply, half-turning to squint down the road.

"Watching me. That back-of-the-neck feeling."

I saw his face clearly by the light of the torch. "Ah yes. Watching you. That'll be the moor."

"The Moor?" I said in astonishment. I knew where I was, of course, but for an instant the book I had been reading on the train was closer to mind than my sense of geography, and I was confronted by the brief mental image of a dark-skinned scimitar-bearing Saracen lurking along a Devonshire country lane.

"Dartmoor. It's just there." He nodded over his shoulder. "It rises up in a great wall, four or five miles away, and although you can't see it from here, it casts a definite presence over the surrounding countryside. You'll meet it tomorrow. Come," he said, turning up the road. "Let us take to the warm and dry."

I left the torch on now. It played across the hedgerow on one side and a stone wall on the other, illuminating for a moment a French road sign (some soldier's wartime souvenir, no doubt), giving us a brief glimpse of headstones in a churchyard just before we turned off into a smaller drive. A thick layer of rotting leaves from the row of half-bare elms and copper beeches over our heads gave way to a cultivated garden—looking more neglected than even the season and the rain would explain, but nonetheless clearly intended to be a garden—and finally one corner of a two-storey stone house, the small pieced panes of its tall windows reflecting the torch's beam. The near corner was dark, but farther along, some of the windows glowed behind curtains, and the light from a covered porch spilled its welcome out across the weedy drive and onto a round fountain. We ducked inside the small space, and had begun to divest ourselves of the wettest of our outer garments when the door opened in front of us.