The Mascot (20 page)

Authors: Mark Kurzem

When he'd finished, Lobe poured himself yet another schnapps. “That's what we did for your father,” he said proudly. Lobe had had so much to drink that I worried he'd drop off to sleep again.

But instead the schnapps fueled his ire, and he began to rail a second time against those who had tarnished his reputation. As he gesticulated somewhat wildly with one hand, he pulled a folded sheet of paper from his box with the other. He gripped the paper tightly and rubbed it repeatedly, almost neurotically, with his thumb. It struck me as a rather childish gesture.

“After the war they called us Nazis,” he said, outraged. “They said that we Latvians welcomed the Nazis when they entered our country. Absurd! We didn't follow their philosophy. We hoped the Germans would be a means to an end: to free us from Soviet oppression. That's all! They said that we turned on our own people. But they were not our people! They were partisans. Bolsheviks! Traitors!”

I remember thinking to myself “and Jews as well.”

Lobe claimed to me that he'd had one wish his entire lifeâto see Latvia free, and that was not a crime. At the time I knew little about Latvia's role in the war, but I recalled enough to see that he was trying to justify Latvia's past. There was little I could do to stem the tide of his mounting hysteria as he began to rave, running his words together into an indecipherable mixture of Latvian, Swedish, and German.

His rant was reaching a crescendo and he'd become quite disturbed, almost apoplectic. Mrs. Lobe must have been listening from the kitchen because suddenly she rushed in with a tablet and a glass of water, anxiously reminding him about his high blood pressure. He swallowed it and then sank back on the sofa. I waited beside him in silence, until he had calmed himself, and after several minutes his wheezing subsided.

All through his tirade, and even now, as he rested, Lobe had continued to wave the paper around in his fist. When I asked him what it was, he was startled. He appeared to have forgotten that it was still in his hand and looked at it curiously, but ignored my question. He returned the paper to the box. Then, shifting awkwardly in his seat so that he was almost facing me, he said with finality, “War is a nasty business. And I have paid the price.”

I was young, with no experience of war. I didn't know how to respond, so I nodded, putting on a grave expression that I hoped was appropriate. And the truth was that I did sincerely feel for him and was indignant on his behalf.

By this time it was getting late, and I thought it best that I should leave. Besides, I'd grown increasingly uncomfortable. Intuitively, I knew something was amiss, but I couldn't put my finger on it.

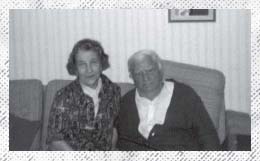

Before I departed, I took a photograph of the commander and his wife together on the sofa. For an instant, they both seemed so vulnerable as they sat there, looking up into the camera lens as I focused. Poor Mrs. Lobe gave a weak, tired smile, while beside her, Mr. Lobe's face regained its sharp, bullish expression. The abruptness of the transformation unnerved me.

Mr. and Mrs. Lobe at home in Stockholm, early 1980s.

But still he wasn't well enough to see me to the door. He couldn't even rise to shake my hand. Instead he gave me a salute from where he was seated and told me that he was sad to see me go; he promised to stay in touch.

Mrs. Lobe unbolted the door to let me out, and when she shut it behind me, I heard her refasten the locks. It struck me as quite pathetic, and I had to pause outside for a moment; I felt quite moved by their circumstances. I sensed that I would never meet them again.

I departed Stockholm, aware that much lay beneath the bonhomie of my father's relationship with the Lobes but perplexed as to what it could be. I never told my father the truth about what had taken place in Sweden. I'd merely described it as pleasant and said it was good to have met Lobe. He'd never asked me more about it. Now I was certain that it was the key to something very significant.

I also had questions about the other men in my father's life. UncleâJekabs Dzenisâhad been a central part of my own life as I grew up in Melbourne. To me he was an austere and formidable figure, but I had never sensed any malevolence in his character; rather I thought of him and of his wife, Emily, as my adoptive grandparents. I fondly remembered driving with him to his holiday cottage in the countryside outside Melbourne. En route, to try to engage him, I'd recited poetry by Goethe, Schiller, and Heine in German. As the car wove its way through the narrow, hilly lanes, he gently corrected my mistakes in memorization and pronunciation.

As a child I had felt sorry for the Dzenises, whom I saw as being buffeted by fate, pawns in the theater of war. Now my sympathy had evaporated: Uncle had deceived me about who he wasâand their exodus from the fatherland seemed less a cruelty and more an attempt to cover their tracks.

Jekabs and Emily Dzenis were dead, but I hoped that I could turn to surviving relatives for more information about the role they had played in my father's past. I knew I'd have to tread cautiously while ferreting out their wartime sympathies and associations.

Then there was Jekabs Kulis, the soldier who had actually saved my father from the firing squad. He would be in his late seventies or early eighties by now. Was he still living near New York City? If not, where?

I drifted into a light doze, only to wake with a start as heavy turbulence hit the plane, causing it to shudder violently. I gave up on trying to sleep.

During the seemingly interminable hours that followed, I couldn't help but reflect on my father, even though I had tried deliberately to avoid doing so. My image of him had been turned upside down.

On one hand, he was still my father, the person I thought I knew. We would banter and joke easily with each other, and had what many would see as a good relationship. But as is common with fathers and sons, there was also a suffocating silence between us whenever our emotions were exposed. We never confronted each other, and as I matured into adulthood I understood that we could both live comfortably with that tacit agreement.

But it was also true that my father had lived a double life, and I didn't really know who he was.

Why had my father kept the truth from us? While I could accept what he had said to me about protecting his family from the shadows of his past, I didn't believe that this was the full story. Were there threats from other sources that he was yet still unwilling to discuss?

Was he frightened of himself and of his own memories? To never speak of one's memories did not mean that one had escaped them. I could not imagine what it would be like to live in the imminent danger of the revelation one's self.

When my father looked at my brothers and me, did he see what had been cruelly taken from him? Did he long to utter the words “my brother” or “my sister,” words that my brothers and I used without a second thought?

Above all, I wondered how my father had managed to keep his past “unspoken” all these years. Had his enduring silence been a form of survival he was as unwilling to relinquish as his life?

Questions like these plagued me during the flight, and I realized I would have to let my father fill in the details of his story at his own pace. I decided to walk to the rear of the plane to stretch my limbs.

I had paid little attention to the other passengers, so I was surprised when I entered the rear cabin and found myself in the midst of what appeared to be a religious jamboree. On the side of the plane where I stood, four Orthodox Jews draped in their traditional prayer shawls and wearing yarmulke had gathered in the space around the emergency exit. In low voices they were chanting in unison while davening toward the wall of the cabin. I felt inexplicably confronted by their behavior and turned away, only to notice that on the far side of the cabin a much larger prayer meeting was going on. It seemed that most of the rear cabin had been occupied by a group of Japanese Christians, perhaps en route to a pilgrimage in Europe. Standing at the front of the group, a man in a priest's collar was leading row upon row of followers in slightly fevered prayer.

I moved unsteadily back toward my seat, feeling lightheaded and disconcerted.

Half an hour later the plane entered its holding pattern, circling to the west of the airport and waiting for permission to land. But I felt anchorless and directionless, cast adrift on a sea between past and present. Filled with an inchoate fear that the mysteries of my father's past would be the harbinger of a dangerous squall for our whole family, I had no idea when and where I would reach safe harbor again.

OXFORD

E

ventually I settled back into my routine in Oxford, but my academic research quickly took a backseat to my father's story, which now dominated my thoughts.

In the weeks that followed my return, I made numerous phone calls to my father; the little dance that had begun over the telephone in Tokyo continued. Whenever I tried to broach what had happened to him, let alone the mere existence of the tape and its contents, my father would lapse into an unshakable silence before either abruptly changing the topic or, more often, rapidly handing the telephone to my unsuspecting mother.

I soon grew tired of pursuing my elusive father. In the meantime, I would gather what scraps of his past were available to me and see where they would lead. I retrieved the videotape from where I'd hidden it in the bottom drawer of the desk in my study, perhaps in an unconscious emulation of the way my father had secreted his case. Then I found myself repeating the ritual I'd developed in my studio in Tokyo. I spent an entire weekend with the curtains drawn, playing the tape repeatedly. Only this time, I coolly jotted down further details of his story. By Sunday evening, I had filled a small notebook with observations and queries and, after I had returned the video to its hiding place, I settled into an armchair and began to review my notes.

Ultimately, my father's recollections were impressionistic. With few exceptions, they lacked objective markers that could pinpoint a precise moment or place. I had a handful of names of places and people from which to begin my researchâLaima chocolate factory, Valdemara Street, Riga, Carnikava, the Volhov swamps, Lobe, Dzenis, and Kulisâand the mysterious words “Koidanov” and “Panok.” It wasn't much to go on. My father's vivid account of the burning of people in a synagogue was unaccompanied by a place or a time.

While I did not hold my father responsible for the nature of his memoriesâone would expect little more from a terrified child's point of viewâI felt thwarted by them. By the time I'd reached the last page of my notes, I realized that my frustration had boiled over unconsciously. In the margin, I had jotted down words such as “silence,” “memory,” and “truth,” which I had then underlined once or twice for further emphasis.

I lay on my bed, mulling over the information that I did have. Foremost in my mind were “Koidanov” and “Panok,” the words my father had revealed to me at the Café Daquise in London. Where did they come from? Were they the names of people or places? Did they have any connection with his family? My father claimed that he'd held these names inside him for as long as he could remember. Had the extermination itself imprinted them on his soul?

I was intrigued, too, by my father's cryptic recollections of his early family life. He had said that he had a younger brother and a baby sister. What were their names? How old were they when they were killed? His memories of his own father were baffling: sometime after being told that his father was dead, Alex saw him. His father lowered himself from a hole in the ceiling of the family home to gently whisper good-bye to Alex.

Finally, my father was adamant that on the night prior to the extermination of his village his mother had taken him onto her lap and told him that they were all to die in the morning.

Without the name of my father's family or a village to go on, how would I ever uncover the truth of these memories or give him back his original identity?

I lived in a university town populated with some of the world's finest scholars. It was only natural, then, that I begin my search for the meaning of Koidanov and Panok in Oxford. Through academic contacts, I was put in touch with a number of Holocaust historians.

Their responses disappointed me: most of the experts were unwilling to listen to my father's story with an open mindâtheir reservations stemmed from the fact that his recollections were too vague and anecdotal. I was surprised by this: I thought my father's recollections had been quite sharp for a young child. And I considered anecdotes important to our understanding of the Holocaust. Because most survivors had been significantly older than my father at the time of the Holocaust, their stories contained more objective signposts, most notably the central symbol of the Holocaust: the concentration camp. My father's story had no such icon. I didn't think this would matter, but I was to realize soon enough my naïveté would be evident.

Three professors were intrigued enough to fit me into their busy schedules, and I set up appointments to meet one of them in London and the other two in Oxford. In advance of our meetings, I sent each one an outline of my father's story. As it turned out, all three took a depressingly skeptical stance toward my father's story. Professor M., a distinguished historian at Oxford, delivered the most vehement critique.

Our meeting took place in his office in one of Oxford's most prestigious colleges. He welcomed me warmly. Within moments of shaking my hand, he told me that he had conducted more than three decades of extensive research into the Holocaust, adding that he was a man who had heard many incredible stories of survival. My father's story, he said, was the most incredible.

I noted some reticence in his voice, but I put it out of my mind as he ushered me graciously into his room. He poured me a cup of coffee and offered me a comfortable armchair, while he sat behind his desk.

I began to describe my father's story in closer detail. He did not interrupt me, but occasionally nodded his head or smiled thinly in response to something I said. When I had finished speaking, he began to cross-examine me about details of the story. At the end of our lengthy exchange, he took a gulp of his cold coffee and then offered me his opinion. He had heard of neither Koidanov nor Panok and was unable to place them as the names of persons or locations.

I was prepared at that moment to let the matter rest. He had not been able to help me. However, before I could even thank him, he raised a finger to interrupt me.

“I cannot deny the story outright,” he said. “The broad canvas of your father's story may be true, but not in all of its details. Some of them are so fantastic as to be improbable.”

I was flabbergasted.

“Which ones exactly?” I asked.

It seemed that he had prepared for our discussion. He rested his elbows on the desk and began to tap his fingertips gently together. He consulted a sheet of paper. As I waited for him to speak, I found myself distracted by the sight of his delicately manicured fingernails.

“What bothers me most of all,” he said, “is your father's claims about the manner in which he survived. No child of five could have survived under such conditionsâalone in a forest during a northern Europe winter. Even soldiers and partisans found it hard to withstand the freezing conditions and depredations of the situation.

“And over and above that,” he continued, “why would these Nazisâany Nazisâkeep a Jewish boy alive? What possible advantage would it have had for them?”

I explained to him again that as far as I knew only Jekabs Kulis, and nobody else, had known my father was Jewish, and he alone had instructed my father to keep his Jewish identity hidden. It had involved no great conspiracy of silence among a number of men. But the professor found this explanation hard to accept.

“There was no way that your father would've been able to keep it secret,” he said irritably. “Somebody would have caught your father out at some stage. And apart from that, no child of that age could be capable of such vigilance in protecting himself. It would have required a superhuman effort, not only physically: the mental strain would've been unbearable.

“What also creates doubt in my mind is your father's account of his escape from his village. To be frank with you, it would have been absolutely impossible for his mother to have known what was going to happen to her family the following morning,” he said. “From the chronology you have conveyed to me, I am certain that the extermination must have happened sometime in perhaps autumn or early winter 1941. Given my knowledge of history, it is likely to have taken place somewhere in Russia.

“Now here is the difficulty I have with the incident. You have heard of the Wannsee Conference, I take it?”

I nodded.

“The Wannsee Conference took place in January 1942 and is held to be the time when the program and methods for the mass extermination of the Jews became systematized.

“Prior to that was a period that I call the proto-Holocaust, when the Nazis experimented with a variety of methods of extermination. At that time they began to clear out the Jewish communities in the villages of eastern Europe. They did this to make way for the deportation and temporary resettlement of western European Jews there. The Nazis moved swiftly from village to village in units known as Einsatzgruppen, or extermination squads, German-led but manned mainly by Baltic volunteer forces, police brigades and the like, carrying out

Aktionen,

as they called their ruthless work.

“The Jewish population in the villages would have been largely unsuspecting about their imminent fate. There are two key things here. Firstly, the communication between villages for the most part would have been poor, so it was highly unlikely that the Jews in these villages knew about presence of the Einsatzgruppen until they were literally upon them. The second thing is that the Jews from these villages had a long history of being subject to pogroms, in which the men and boys may have been killed, but not the women and children. There was no way they, including your father's motherâa simple peasant woman, according to your fatherâwould have any inkling that a new imperative for extermination that required the liquidation of all the Jewish men, women, and children in her village had come into existence.”

I didn't know how to respond to his assertion. Professor M. was a world-renowned expert in the field. Yet I could not believe that my father was lying about what he remembered. Certainly my father was a great storyteller. The tales of his adventures in the Australian outback and elsewhere had always been slightly embellishedâeven as a child I'd sensed thisâbut the raw pain and grief I had witnessed on my father's face were another matter. Unlike the voluble and masterful raconteur I knew, he had struggled with every syllable as he endeavored to give life to his experiences.

I'd been absorbed in my reflections and was brought back to the present by a tapping sound. The professor was impatiently drumming his fingers on his blotter. It occurred to me that he'd grown bored with the discussionâor worse, he didn't believe entirely my father's version of events at all. He looked at his watch.

“I am sorry to have to say this to you, young man,” he said, waving his hand in a dismissive gesture, “but it's altogether too implausible.”

My suspicions had been correct. “Are you saying that my father is lying?” I blurted out. For a moment, he was taken aback and looked worried. Then he regained his composure.

Perhaps he thought better of what he'd just said, because suddenly he adopted a more conciliatory tone and suggested that we move to one of the college's common rooms. I agreed readily. I wanted to be on more neutral ground.

It was late afternoon and the darkened common room was deserted. The professor discreetly closed the heavy wooden door behind us as we entered, thereby softening the sounds of the outside world. We made ourselves comfortable in deep leather armchairs that faced each other. A mood of calmness and civility prevailed. I waited for the professor to speak.

“Please let me give you some advice,” he said. This time there was a note of sympathy in his tone. “I do not necessarily deny that an extermination took place,” the professor continued from where he had left off. “But I cannot accept that events unfolded as your father has described them. In essence, that is my problem with the entire story. He must have embellished it.”

“It's not clear to me why he, or anybody, would embellish such a litany of horror,” I said, trying to remain even-tempered. “What purpose would it serve? What do you think actually happened, then?”

“Only your father knows. It is highly likely that somewhere inside himself, your father feels guilty about his own survival, however it may have occurred, so he has dramatized it to make it seem more out of his own control. For example, what child would have the wherewithal to escape in the way that he claims he didâand the personal resources to survive in the forest for such a long time? The wolves at night, the corpses in the forest, tying himself in the trees, caught by the woodsman! It has all the trappings of a fairy tale told to exaggerate his own innocence.”

“You're not serious!” I said angrily.

The professor held up his hand to indicate that he had not finished what he wanted to say. “And this question of how he was found,” he said. “Perhaps he volunteered to go with the soldiers in order to save himself⦔

My sense of outrage was almost palpable. My heart was beating so loudly in my ears that I could barely hear my own response.

“Of course he wanted to live. Who wouldn't?” I raised my voice. “But that didn't mean that he made a conscious free choice to join the soldiers. What child of five volunteers for anything?”

The professor indicated with both hands that I should quiet down. I looked around me and noticed a member of the staff tidying newspapers in the far corner of the room.