The Mascot (36 page)

Authors: Mark Kurzem

My father turned in all directions.

“Over there,” he said, pointing at a track off to the right. “That's the direction I came from when I ran away from home.” Then the sequence of events seemed to get more confusing. “It happened during the night after we'd been led down the hill, after my mother had told me that we were all going to die in the morning.”

He headed over to the path and began to retrace his steps from the night of his escape. He walked tentatively across the open space as if trying to find his way in the dark.

“Up there,” he said, this time pointing off slightly to the left. “That's where I headedâup the hill and into the trees.”

We all turned our heads in that direction. There was a hillock with a few trees at its peak.

My father appeared to forget about us once again and strode across to the hill. Though I felt slightly ashamed to do so, I hurried ahead of the others so that I could continue to eavesdrop on his words.

“Not as steep as I remember,” he said. “It seemed like a mountain at the time. I climbed as fast as my legs could take me.”

My father stopped and stared back down the slope with a frown on his face. But he was unaware of the scene unfolding in front of him: my mother had run out of breath and was now struggling to climb the slope. Fortunately, at that moment I saw Galina and Erick come to my mother's aid, and together they made their way slowly in our direction.

By this point my father had reached the top of the hillock and, hand to cheek, stood very still looking down over the vista below us. He nodded grimly. “Yes,” he said. “Yes.”

At that moment the others reached us.

“You okay, Mum?” I asked. She nodded, still quite breathless.

“Trees, Erick,” my father called out. “Were there more trees here?”

My father hadn't even noticed that my mother had joined him. And for a moment I was annoyed by his lack of regard for her condition.

“Yes,” Erick replied. “I used to play up here as a child sometimes. They removed many of the trees years ago.”

My father was silent, and we waited for him to speak.

“In the morning I saw the people being led from over there. Near that cottage. I was peering between the trees. They were lined up on that hill as the soldiers pushed and prodded them down in groups,” my father said, indicating the path we had taken earlier. “Then I saw my mother and the children and”âmy father gasped as if the air had violently been knocked out of himâ“the rest of my family were among them, and they were almost thereâ¦the pit.”

My father took a deep breath. “My mother was holding my brother and sister. She looked away from what was going to happen to her and that's when I am sure she saw me up among the trees. For a split second I saw her eyes. She recognized me.

“I am sure that she must have been beside herself with worry when she'd woken in the morning and found me gone. At least she knew I was alive, for what that was worth⦔

I stared at my father, who seemed to be in a state of shock. “I bit my hand not to cry out,” he said in a strangled whisper. I saw him raise his hand and bite it as he had on that day, as if reliving the horrific scene. A trickle of blood dripped down his wrist and onto the cuff of his shirt.

My mother had noticed, too, at the same instant. “Alex!” she cried out, but he didn't hear her.

Panicked, she dashed forward and began to shake him. “Alex!” She was alarmed. “Stop it! Please, stop it, Alex!”

My father returned to us. His face was ashen and he seemed fragile and disoriented. He stared down at his bleeding hand. My mother pulled out her handkerchief and gently bandaged it, while my father stood like a helpless child.

“C'mon, luv, let's get out of here,” my mother said, putting her arm in his and moving him away from the edge of the hill. My father didn't resist.

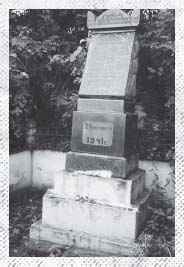

As we made our way down the hill, Erick pointed us in the direction of a simple monument on the right. It was the memorial to “the martyrs of the Koidanov massacre,” as he described them. It had obviously been neglected for many years and was partly obscured by the bushes and tall grass.

“This way!” Erick ordered, and, dashing ahead of us, he began to tear away at the foliage. By the time we reached him, he had managed to clear the debris from around the dedication plaque.

Reading aloud, Galina translated it for us: “Here lie sixteen hundred men, women, and children who suffered at the hands of the Fascist invaders.”

My father stepped forward with his head bowed. My mother, who stood close behind, passed him three roses that she'd had the foresight to bring with her from the hotel.

We stood quietly as my father placed the roses at the base of the memorial, his mother's gravestone.

As we made our way slowly back from the site of the mass grave, my father stopped and took me to one side. “This is my village,” he whispered. “I'm sure of it. But I'm still not certain that I'm a Galperin.” Then, leaving me with that thought, he took off in pursuit of the others, who had reached the base of the hill.

We had been so absorbed in our search, we hadn't noticed the sun come out. Although it threw off only the palest spring light, its mere presence alleviated some interior chill. We'd also been oblivious to the attention our visit had attracted.

A few yards away, a number of children had gathered by a bench, staring at us with both shyness and frank curiosity. One of the boys waved to us, indicating that we were welcome to make use of the bench. He wore a cheeky grin, and, as we approached to sit down, he called out to us, “Hello, Mister America.”

“Not America,” Galina explained. “Australia.”

This provoked a wide-eyed response. We must have seemed very exotic. The children began to gather around chanting “kangaroo” at us. My mother burst out laughing with pleasureâshe loved being around childrenâand took a seat on the bench, as did my father and Erick. I remained standing and only half listening to my mother and father as they tried to tell them more about Australia.

I was restless. I looked around and only then noticed that a handful of people had come out onto the front porches of their houses and were observing us silently. From where I was standing they all appeared to be quite elderly, and my immediate thought was whether any of them had witnessed the massacre. I wondered whether they had been the ones my father had remembered standing on their balconies, laughing and chatting as women and children were led to their deaths.

I suggested to Galina that she and I walk past these houses. I was not surprised when a man, no more than seventy years old, called out to us from where he was seated on his front porch. We stopped.

His face was alert with curiosity. He spoke and Galina translated. “What are you doing here?”

“I am trying to find out more about what went on in this square during the war,” I said.

“The massacre by the Fascists?” He fixed me with a shrewd, assessing gaze. “Why?” he asked.

“My father's family perished in it,” I answered.

“Jews, were they?”

I nodded.

The man gave a low grunt and shifted the blanket that covered his knees.

“I saw it,” he said, after a silence of several moments. “I grew up in this house and from here I could see everything. I remember it better than what I ate for lunch today.” He chuckled to himself.

“What happened that day?” I asked.

“It began in the middle of the night. We were woken by the sound of men in the square. Father and I went out onto the porch, as did some of our neighbors. Soldiers and a group of menâabout twenty or thirty of themâwere there. We couldn't understand what was going on. The soldiers were guarding the men who were digging.

“One of the officers caught sight of us and ordered us back indoors, telling us that we'd be put to work digging as well if we didn't disappear.

“The sound of the digging went on till first light. That's when I sneaked a look through the window.” He indicated the window behind him. “I couldn't believe my eyesâthere was an enormous gaping hole in the earth where the square had been.”

The man rose unsteadily to his feet and shuffled to the edge of the veranda and closer to us. Slowly he raised his arm and pointed in the direction of the slope we had descended earlier with my father.

“They came from there,” he said. “Women. Children, babies, old people. Jews, they were. Hundreds of them. The queue led all the way back up the hill as far as the eye could see.

“The babies were wailing and many of the children were in tears. Their mothers were trying to calm them, but the soldiers showed no patience. They prodded at the little ones with their bayonets, screaming at them to shut up.”

His finger shifted in the direction of where my parents were still seated on the bench. “The soldiers pushed and shoved them down there. And over there, near the memorial, that's where the officers stood. You can see that it's higher than the square, so it gave them a good view over the crowd. They were German; their uniforms were different than those of the soldiers.”

The memorial to the martyrs of Koidanov at the site of the massacre.

The man paused for a moment.

“At the base of the hill, the Jews were put into groups of about ten or twelve. Soldiers forced them to undress and then lined them up in front of the pit. Then another group of soldiersâwith riflesâstepped forward.

“I knew by then why the earth had been dug up, and those Jews knew what was going to happen to them. Not a single one of them made any effort to fight back or run away. True, there was nowhere for them to flee in the face of those men and their weapons. But better that than give up the way they didâ¦

“The soldiers raised their rifles and fired into the line so that the people fell backward into the hole. Sometimes if a body didn't fall in the right way, a soldier would step forward and kick it the rest of the way in.

“They didn't waste their bullets on the babies or children; they simply used the bayonet. A quick sharp lunge and that was the end of that one.”

Throughout his description, the man's voice had remained low-key and the expression on his face blank so that it was impossible to tell how this had affected him.

“This was repeated several times,” he continued. “A new group was shot and shoved into the pit. Like clockwork. Even though you could see that many of the soldiers were drunk, they were efficient.

“And all the way up that slope the Jews queued in silence, watching what was happening belowâto their friends and neighbors, members of their familyâand waiting for their turn.”

The man turned away from the open space before him. If it had once been the village square, it was now a derelict place used by children unaware of its poisonous history.

“It was then that the strangest thing happened.” His hand trembled as he raised his arm to the sky. “Without any warning at all, I swear, the sky turned black and the heavens opened. Not just rain, but a deluge. A flood of such power.

“In seconds the square turned into a muddy mess. The soldiers and the Jews were drenched and slipping all over the place. The Jews began to panic. I could understand whyâI did, too, from the safety of my house. It was mayhem. I could see the officers giving orders for the soldiers to control the crowd.

“And then the thunder began, and bolts of lightning began striking so close to the ground. It was as if God himself had descended and was going to destroy us all.” The man crossed himself before continuing.

“Even the soldiers became spooked: some of the firing squad had put down their rifles. They didn't want to continue with the killings. The commanding officer must've made the decision to stop because next thing the Jews were being forced back up the hill and into their houses. Even the ones who were already naked and about to die were forced to dressâthey grabbed at any piece of clothing from the pile that had been dumped by the pit from the previous victimsâand then ordered up the hill.

“After that I saw the remaining soldiers gather their weapons and packs and head off. They left the pit just as it was: open and piled with bodies, and filling up with water. The rain didn't cease all day, not for a single moment, until nightfall.”