The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love (57 page)

Read The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love Online

Authors: Oscar Hijuelos

Cesar dancing with his white golden-buckled shoes, darting in and out like agitated compass needles, and he went back running through Las Piñas as if he were a little kid again, blowing horns and banging pots and making noise in the arcades . . .

Floating on a sea of tender feelings, under a brilliant starlit night, he fell in love again: with Ana and Miriam and Verónica and Vivian and Mimi and Beatriz and Rosario and Margarita and Adriana and Graciela and Josefina and Virginia and Minerva and Marta and Alicia and Regina and Violeta and Pilar and Finas and Matilda and Jacinta and Irene and Jolanda and Carmencita and María de la Luz and Eulalia and Conchita and Esmeralda and Vivian and Adela and Irma and Amalia and Dora and Ramona and Vera and Gilda and Rita and Berta and Consuelo and Eloisa and Hilda and Juana and Perpetua and María Rosita and Delmira and Floriana and Inés and Digna and Angélica and Diana and Ascensión and Teresa and Aleida and Manuela and Celia and Emelina and Victoria and Mercedes and . . .

And he loved the family: Eugenio, Leticia, Delores, and his brothers, living and dead, loved them very much.

Now, in his room in the Hotel Splendour, the Mambo King watched the spindle come to the end of the “The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love.” Then he watched it lift up and click back into position for the first song again. The clicking of the mechanism beautiful, like the last swallow of whiskey.

When you are dying, he thought, you just know it, because you feel a heavy black rag being pulled out of you.

And he knew that he was going, because he felt his heart burning with light. And he was tired, wanting relief.

He started to raise the glass to his lips but he could raise his arm no longer. To someone seeing him there, it would look as if he were sitting still. What was he thinking in those moments?

He was happy. At first, things got very dark, but when he looked again, he saw Vanna Vane in the hotel room, kicking off her white high heels and hitching up her skirt, saying, “Would you do me a favor, honey? Undo my garters for me?”

And so he happily knelt before her, undoing the snaps of her garters, and then he slid her nylons down and planted a kiss on her thigh and then another on her buttock, where the softest skin, round and creamy, peeked out from her panties, and he pulled them down to her knees and with his majestic, ravaged visage between her legs he gave her a deep tongue-kiss. And soon they were on the bed, frolicking as they used to, and he had a big erection and no pain in his loins, so big that her pretty mouth had to struggle with the thick and cumbersome proportions of his sexual apparatus. They were entangled for a long time and he made love to her until she broke into pieces and then a certain calm came over him and for the first time that night he felt like going to sleep.

T

HE NEXT MORNING, WHEN THEY

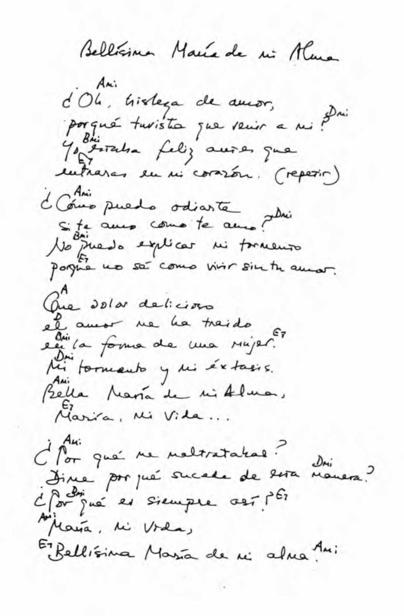

found him, with a drink in his hand and a tranquil smile on his face, this slip of paper, just a song, lying on the desk by his elbow. Just one of the songs he had written out himself:

W

HEN I CALLED THE NUMBER

that had been listed on Desi Arnaz’s letterhead, I expected to speak with a secretary, but it was Mr. Arnaz himself who answered the phone.

“Mr. Arnaz?”

“Yes.”

“I’m Eugenio Castillo.”

“Ah, Eugenio Castillo, Nestor’s son?”

“Yes.”

“Nice to hear from you, and where are you calling from?”

“From Los Angeles.”

“Los Angeles? What brings you out here?”

“Just a vacation.”

“Well then, if you are so close by, you must come to visit me.”

“Yes?”

“Of course. Can you come out tomorrow?”

“Yes.”

“Then come. In the late afternoon. I’ll be waiting to see you.”

It had taken me a long time to finally work up the nerve to call Desi Arnaz. About a year ago, when I had written to him about my uncle, he was kind enough to send his condolences and ended that letter with an invitation to his home. When I finally decided to take him up on his offer and flew to Los Angeles, where I stayed in a motel near the airport, I had wanted to call him every day for two weeks. But I was afraid that his kindness would turn into air, like so many other things in this life, or that he would be different from what I had imagined. Or he would be cruel or disinterested, or simply not really concerned about visitors like me. Instead, I drank beer by the motel swimming pool and passed my days watching jet planes crossing the sky. Then I made the acquaintance of one of the blondes by the pool, and she seemed to have a soft spot for guys like me, and we fell desperately in love for a week. Then ended things badly. But one afternoon, a few days later, while I was resting in bed and looking through my father’s old book,

Forward America!,

just the contact of my thumb touching the very pages that he—and my uncle—had once turned (the spaces in all the little letters were looking at me like sad eyes) motivated me to pick up the telephone. Once I’d arranged the visit, my next problem was to get out to Belmont. On the map, it was about thirty miles north of San Diego along the coast, but I didn’t drive. So I ended up on a bus that got me into Belmont around three in the afternoon. Then I took a cab and soon found myself standing before the entranceway to Desi Arnaz’s estate.

A stone wall covered with bougainvillea, like the flower-covered walls of Cuba, and flowers everywhere. Inside the gate, a walkway to the large pink ranch-style house with a tin roof, a garden, a patio, and a swimming pool. Arched doorways and shuttered windows. Iron balconies on the second floor. And there was a front garden where hibiscus, chrysanthemums, and roses grew. Somehow I had expected to hear the

I Love Lucy

theme, but that place, outside of birdsong, the rustling of trees, and the sound of water running in a fountain, was utterly tranquil. Birds chirping everywhere, and a gardener in blue coveralls standing in the entranceway of the house, looking over the mail spread out on a table. He was a white-haired, slightly stooped man, thick around the middle, with a jowly face, a bundle of letters in one hand, a cigar in the other.

As I approached him, saying, “Hello?” he turned around, extended his hand, and said, “Desi Arnaz.”

When I shook his hand, I could feel his callused palms. His hands were mottled with age spots, his fingers nicotine-stained, and the face that had charmed millions looked much older, but when he smiled, the young Arnaz’s face revealed itself.

Immediately he said, “Ah, but you must be hungry. Would you like a sandwich? Or a steak?” Then: “Come with me.”

I followed Desi Arnaz down his hallway. On the walls, framed photographs of Arnaz with just about every major movie star and musician, from John Wayne to Xavier Cugat. And then there was a nice hand-colored glamour-girl photograph of Lucille Ball from when she was a model in the 1930s. Above a cabinet filled with old books, a framed map of Cuba, circa 1952, with more photographs. Among them that photograph of Cesar, Desi, and Nestor.

Then this, in a frame:

I come here because I do not know when the Master will return. I pray because I do not know when the Master will want me to pray. I look into the light of heaven because I do not know when the Master will take the light away.

“I’m retired these days,” Mr. Arnaz said, leading me through the house. “Sometimes I’ll do a little television show, like Merv Griffin, but I mainly like to spend my time with my children or in my garden.”

When we had passed out of the house through another arched doorway, we reached a patio that looked out over Arnaz’s trees and terraced gardens. There were pear, apricot, and orange trees everywhere, a pond in which floated water lilies. Pinks and yellows and brilliant reds coming out of the ground and clustered in bushes. And beyond all this, the Pacific Ocean.

“. . . But I can’t complain. I love my flowers and little plants.”

He rang a bell and a Mexican woman came out of the house.

“Make some sandwiches and bring us some beer. Dos Equis, huh?”

Bowing, the maid backed out through a doorway.

“So, what can I do for you, my boy? What is it that you have there?”

“I brought something for you.”

They were just some of my uncle’s and father’s records from back when, Mambo King recordings. There were five of them, just some old 78s and a 33, “The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love.” Looking over the first of the records, he sucked in air through his teeth fiercely. On the cover of that record my father and uncle were posed together, playing a drum and blowing a trumpet for a pretty woman in a tight dress. Putting that aside, and nodding, he looked at the others.

“Your father and uncle. They were good fellows.” And: “Good songwriters.”

And he started to sing “Beautiful María of My Soul,” and although he couldn’t remember all the words, he filled in the missing phrases with humming.

“A good song filled with emotion and affection.”

Then he looked over the others. “Are you selling these?”

“No, because I want to give them to you.”

“Why, thank you, my boy.”

The maid brought in our sandwiches, nice thick roast beef, lettuce, and tomato, and mustard, on rye bread, and the beers. We ate quietly. Every now and then, Arnaz would look up at me through heavy-lidded eyes and smile.

“You know,

hombre,

” Arnaz said, chewing. “I wish there was something I could do for you.” Then: “The saddest thing in life is when someone dies, don’t you think,

chico?”

“What did you say?”

“I said, do you like California?”

“Yes.”

“It’s beautiful. I chose this climate here because it reminds me of Cuba. Here grow many of the same plants and flowers. You know, me and your father and uncle came from the same province, Oriente. I haven’t been back there in over twenty years. Could you have imagined what Fidel would have made of Desi Arnaz going back to Cuba? Have you ever been there?”

“No.”

“Well, that’s a shame. It’s a little like this.” He stretched and yawned.

“Tell you what we’ll do, boy. We’ll set you up in the guest room, and then I’ll show you around. Do you ride horses?”

“No.”

“A shame.” He winced, straightening up his back. “Do me a favor, boy, and give me a hand up.”

Arnaz reached out and I pulled him to his feet.

“Come on, I’ll show you my different gardens.”

Beyond the patio, down a few steps, was another stairway, and that led to another patio, bounded by a wall. A thick scent of flowers in the air.

“This garden is modeled after one of my favorite little plazas in Santiago. You came across it on your way to the harbor. I used to take my girls there.” And he winked. “Those days are long gone.

“And from this

placita

you could see all of Santiago Bay. At sunset the sky burned red, and that’s when, if you were lucky, you might steal a kiss. Or make like Cuban Pete. That’s one of the songs that made me famous.”

Nostalgically, Arnaz sang, “My name is Cuban Pete, I’m the King of the Rumba Beat!”

Then we both stood for a moment looking at how the Pacific seemed to go on forever and forever.

“One day, all this will either be gone or it will last forever. Which do you think?”

“About what?”

“The afterlife. I believe in it. You?”

I shrugged.

“Maybe there’s nothing. But I can remember when life felt like it would last forever. You’re a young man, you wouldn’t understand. You know what was beautiful, boy? When I was little and my mother would hold me in her arms.”

I wanted to fall on my knees and beg him to save me. I wanted to hold him tight and hear him say, “I love you,” just so I could show Arnaz that I really did appreciate love and just didn’t throw it back into people’s faces. Instead, I followed him back into the house.

“Now I have to take care of some telephone calls. But make yourself at home. The bar’s over there.”

Arnaz disappeared, and I walked over to the bar and fixed myself a drink. Through the big window, the brilliant blue California sky and the ocean.

Sitting in Desi Arnaz’s living room, I remembered the episode of the

I Love Lucy

show in which my father and uncle had once appeared, except it now seemed to be playing itself out right before me. I blinked my eyes and my father and uncle were sitting on the couch opposite me. Then I heard the rattle of coffee cups and utensils and Lucille Ball walked into the living room. She then served the brothers their coffee.