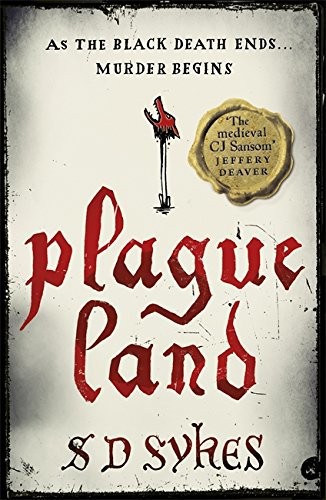

Plague Land

Authors: S. D. Sykes

Plague Land

S D Sykes

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © S D Sykes 2014

Map by Rodney Paull

The right of S D Sykes to be identified as the Author of the

Work has been asserted by her in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be

otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that

in which it is published and without a similar condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious, or are historical figures

whose words and actions are fictitious. Any resemblance

to real persons, living or dead is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 444 78576 0

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For Paul

Contents

Somershill and its environs, West Kent circa 1350

The bubonic plague reached London in the autumn of 1348. Carried in the digestive tract of rat fleas, the Great Mortality went on to kill half the population of England in the following two years.

A Disputation betwixt the body and worms

Take heed unto my figure above

And see how sometime I was fresh and gay,

Now turned to worm’s meat and corruption

Both foul earth and stinking slime and clay

Medieval poem

Anonymous

Prologue

Somershill Manor, November 1350

If I preserve but one memory at my own death, it shall be the burning of the dog-headed beast.

The fire blazed in the field beside the church – its white smoke rising skyward in a twisted billow. Its odour acrid and choking.

‘Let me through,’ I shouted to their backs.

At first they didn’t respond, only turning to look at me when I grabbed at their tunics. Perhaps they had forgotten who I was? A young girl asked me to lift her so she might see the sinner die. A ragged boy tried to sell me a faggot of fat for half a penny.

And then a wail cut through the air. It was thin and piteous and came from within the pyre itself – but pushing my way through to the flames, I found no curling and blackened body tied to a stake. No sooty chains or iron hoops. Only the carcass of a bull, with the fire now licking at the brown and white hair of its coat.

The beast had not been skinned and its mouth was jammed open with a thick metal skewer. I recognised the animal immediately. It was my best Simmental bull, Goliath. But why were they burning such a valuable beast? I couldn’t understand. Goliath had sired most of our dairy herd. We could not afford such waste. And then a strange thing caught my eye. Beneath the creature’s distended belly something seemed to move about like a rat inside a sack of barley. I tried to look closer, but the heat repelled me.

Then the plaintive call came again. A groan, followed by the high-pitched scream of a vixen. I grasped the man standing next to me. It was my reeve, Featherby. ‘How can the beast be calling?’ I said. ‘Is it still alive?’

He regarded me curiously. ‘No, sire. I slaughtered him myself.’

‘Then what’s making such a noise?’

‘The dog-headed beast. It calls through the neck of the bull.’

‘What?’

‘We’ve sewn it inside, sire.’

I felt nauseated. ‘Whilst still living?’

He nodded. ‘We hoped to hear it beg for forgiveness as it burns. But it only screams and screeches like a devil.’

I grabbed the fool. ‘Put the fire out. Now!’

‘But sire? The sacrifice of our best bull will cleanse the demon of sin.’

‘Who told you this?’

‘The priest.’

These words might once have paralysed me, but no longer. ‘Fetch water,’ I shouted to those about me. Nobody moved. Instead they stared at the blaze – transfixed by this spectacle of burning flesh. The ragged boy launched his faggot of fat into the fire, boasting that he was helping to cook the sinner’s heart.

I shook him by the coarse wool of his tunic. ‘Water!’ I said. ‘I command it!’ The boy backed away from me and disappeared into the crowd, only to return sheepishly with a bucket of dirty water. And then, after watching me stamp upon the flames, some others began to bring water from the dew pond. At first it was only one or two of them, but soon their numbers grew and suddenly the group became as frenzied about extinguishing the fire as they had been about fanning it.

When the heat had died down to a steam, we dragged the sweating hulk of the bull over the embers of the fire to let it cool upon the muddy grass. As we threw yet more water over its rump, their faces drew in about me, both sickened and thrilled as I cut through the stitches in the beast’s belly to release its doomed stuffing. It was a trussed and writhing thing that rolled out in front of us – bound as tightly as a smoked sausage.

As I loosened the ropes, the blackened form shuddered and coughed, before gasping for one last mouthful of air. Then, as Death claimed his prize, I held the wilting body in my arms and looked about me at these persecutors. I wanted them to see what they had done. But they could only recoil and avert their eyes in shame.

And what shame. For the face of their sacrifice is stitched into my memory like a tapestry. A tapestry that cannot be unpicked.

But this is not the beginning of my story.

It began before. After the blackest of all mortalities. The Great Plague.

Chapter One

It was a hot summer’s morning in June of this year when I first saw them – advancing towards Somershill like a band of ragged players. I would tell you they were a mob, except their numbers were so depleted that a gaggle would be a better description. And I would tell you I knew their purpose in coming here, but I had taken to hiding in the manor house and keeping my nose in a book. At their head was John of Cornwall, a humourless clenched-fist of a man, whose recent appointment to parish priest rested purely upon his still being alive.

My mother bustled over to me. She had spied the group from our upstairs window, despite her claims to be practically blind. ‘Go and see what they want, Oswald,’ she said, digging her pincer claw into my arm.

I had been trying to decipher last year’s farm ledgers, but the reeve’s handwriting was poor and he had spilled ale upon the parchment.

Mother poked at me again. ‘Go on. It’s your duty now.’

‘Yes, little brother,’ said my sister Clemence, from the corner where she skulked with her sourly stitched embroidery. ‘Though I’m surprised you allow such people to approach by the main gate.’

‘I’ll send Gilbert to deal with them,’ I said, determining not to look up from my work.

‘You can’t. He’s attending to the barrels from the garderobe.’ I had my back to Clemence, but I sensed she was pulling a face. ‘You sent him there yourself, Oswald.’

‘Then I’ll send somebody else.’ I looked to Clemence’s servant Humbert, a boy the size of a door who was holding both of his enormous hands in the air so that Clemence might wind her yarn about his fingers. His boyish eyes never leaving his mistress’s face.

She laughed. ‘You can’t have Humbert either. He’s too busy.’

Abandoning the ledgers, I descended to the great hall where one of the visiting party was now knocking at the main door with intensifying boldness. Lifting the heavy latch I found the culprit to be John of Cornwall, though he quickly dropped his wooden staff on seeing my face and not that of a servant’s on the other side of the threshold. I might have reminded him that such a wooden staff should have been deposited at the gatehouse, like any other potential weapon, but seeing as our gatekeeper was now employed as our valet, I did not challenge him.