The Lying Stones of Marrakech (31 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

If I had to summarize the paradoxes of Darwin's complex persona in a phrase, I would say that he was a philosophical and scientific radical, a political liberal, and a social conservative (in the sense of lifestyle, not of belief)âand that he was equally passionate about all three contradictory tendencies. Many biographers have argued that the intellectual radical must be construed as the “real” Darwin, with the social conservative as a superficial aspect of character, serving to hide an inner self and intent. To me, this heroically Platonic view can only be labeled as nonsense. If a serial killer has love in his heart, is he not a murderer nonetheless? And if a man with evil thoughts works consistently for the good of his fellows, do we not properly honor his overt deeds? All the Darwins build parts of a complex whole; all are equally him. We must acknowledge all facets to fully understand a person, and not try to peel away layers toward a nonexistent archetypal core. Darwin hid many of his selves consummately well, and we shall have to excavate if we wish to comprehend. I, for one, am not fazed. Paleontologists know about digging.

5

The original version of this essay appeared in the

New York Review of Books

as a review of Janet Browne's

Voyaging

.

An Awful Terrible

Dinosaurian Irony

S

TRONG AND SUBLIME WORDS OFTEN LOSE THEIR

sharp meanings by slipping into slangy cuteness or insipidity. Julia Ward Howe may not win History's accolades as a great poet, but the stirring first verse of her “Battle Hymn” will always symbolize both the pain and might of America's crucial hour:

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord;

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible, swift sword;

His truth is marching on

.

The second line, borrowed from Isaiah 63:3, provided John Steinbeck with a tide for the major literary marker of another troubled time in American history. But the third line packs no punch today, because

terrible

now means “sorta scary” or “kinda sad”âas in “Gee,it's terrible your team lost today.” But

terrible

, to Ms. Howe and her more serious age, embodied the very opposite of merely

mild lament.

Terrible

âone of the harshest words available to Victorian writersâ invoked the highest form of fear, or “terror,” and still maintains a primary definition in

Webster's

as “exciting extreme alarm,” or “overwhelmingly tragic.”

Rudyard Kipling probably was a great poet, but “Recessional” may disappear from the educational canon for its smug assumption of British superiority:

God of our fathers, knoum of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine

.

For Kipling, “awful Hand” evokes a powerful image of fearsome greatness, an assertion of majesty that can only inspire awe, or stunned wonder. Today, an awful hand is only unwelcome, as in “keep your awful hand off me”âor impoverishing, as in your pair of aces versus his three queens.

Unfortunately, the most famous of all fossils also suffer from such a demotion of meaning. Just about every aficionado knows that

dinosaur

means “terrible lizard”âa name first applied to these prototypes of prehistoric power by the great British anatomist Richard Owen in 1842. In our culture, reptiles serve as a prime symbol of slimy evil, and scaly, duplicitous, beady-eyed disgustâ from the serpent that tempted Eve in the Garden, to the dragons killed by Saint George or Siegfried. Therefore, we assume that Owen combined the Greek

deinos

(terrible) with

sauros

(lizard) to express the presumed nastiness and ugliness of such a reprehensible form scaled up to such huge dimensions. The current debasement of

terrible

from “truly fearsome” to “sorta yucky” only adds to the negative image already implied by Owen's original name.

In fact, Owen coined his famous moniker for a precisely opposite reason. He wished to emphasize the awesome and fearful majesty of such astonishingly large, yet so intricate and well-adapted creatures, living so long ago. He therefore chose a word that would evoke maximal awe and respectâ

terrible

, used in exacdy the same sense as Julia Ward Howe's “terrible swift sword” of the Lord's martial glory. (I am, by the way, not drawing an inference in making this unconventional claim, but merely reporting what Owen actually said in his etymological definition of dinosaurs.)

*

Owen (1804-92), then a professor at the Royal College of Surgeons and at the Royal Institution, and later the founding director of the newly independent

natural history division of the British Museum, had already achieved high status as England's best comparative anatomist. (He had, for example, named and described the fossil mammals collected by Darwin on the

Beagle

voyage.) Owen was a complex and mercurial figureâbeloved for his wit and charm by the power brokers, but despised for alleged hypocrisy, and unbounded capacity for ingratiation, by a rising generation of young naturalists, who threw their support behind Darwin, and then virtually read Owen out of history when they gained power themselves. A recent biography by Nicolaas A.Rupke,

Richard Owen: Victorian Naturalist

(Yale University Press, 1994), has redressed the balance and restored Owen's rightful place as brilliantly skilled (in both anatomy and diplomacy), if not always at the forefront of intellectual innovation.

Owen had been commissioned,and paid a substantial sum, by the British Association for the Advancement of Science to prepare and publish a report on British fossil reptiles. (The association had, with favorable outcome, previously engaged the Swiss scientist Louis Agassiz for an account of fossil fishes. They apparently took special pleasure in finding a native son with sufficient skills to tackle these “higher” creatures.) Owen published the first volume of his reptile report in 1839. In the summer of 1841, he then presented a verbal account of his second volume at the association's annual meeting in Plymouth. Owen published the report in April 1842, with an official christening of the term

Dinosauria

on page 103:

The combination of such characters⦠all manifested by creatures far surpassing in size the largest of existing reptiles will, it is presumed, be deemed sufficient ground for establishing a distinct tribe or suborder of Saurian Reptiles, for which I would propose the name of Dinosauria.

(From Richard Owen,

Report on British Fossil Reptiles, Part II

, London, Richard and John E. Taylor, published as

Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for 1841

, pages 60â204.)

Many historians have assumed that Owen coined the name in his oral presentation of 1841, and have cited this date as the origin of dinosaurs. But as Torrens shows, extensive press coverage of Owen's speech proves that he then included all dinosaur genera in his overall discussion of lizards, and had not yet chosen either to separate them as a special group, or to award them a definite

name.(“Golden age” myths are usually false, but how I yearn for a time when

local

newspapersâand Torrens got his evidence from the equivalent of the

Plymouth Gazette

and the

Penzance Peeper

, not from major London journalsâ reported scientific talks in sufficient detail to resolve such historical questions!) Owen therefore must have coined his famous name as he prepared the report for printingâand the resulting publication of April 1842 marks the first public appearance of the term

dinosaur

.As an additional problem, a small initial run of the publication (printed for Owen's own use and distribution) bears the incorrect date of 1841 (perhaps in confusion with the time of the meeting itself, perhaps to “backdate” the name against any future debate about priority, perhaps just as a plain old mistake with no nefarious intent)âthus confounding matters even further.

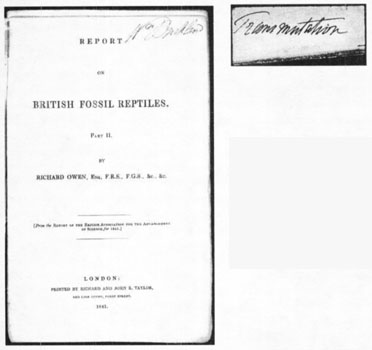

William Buckland's personal copy of Richard Owen's initial report on dinosaurs. Note Buckland's signature on the title page (left) and his note (right) showing his concern with the subject of evolution (“transmutation”)

.

In any case, Owen appended an etymological footnote to his defining words cited just aboveâthe proof that he intended the

dino

in

dinosaur

as a mark of awe and respect, not of derision, fear, or negativity. Owen wrote:“Gr. [Greek]

deinos

[Owen's text uses Greek letters here],fearfully great;

sauros

, a lizard.” Dinosaurs, in other words, are awesomely large (“fearfully great”), thus inspiring our admiration and respect, not terrible in any sense of disgust or rejection.

I do love the minutiae of natural history, but I am not so self-indulgent that I would impose an entire essay upon readers just to clear up a little historical, matter about etymological intentâeven for the most celebrated of all prehistoric critters. On the contrary: a deep and important story lies behind Owen's conscious and explicit decision to describe his new group with a maximally positive name marking their glory and excellenceâa story, moreover, that cannot be grasped under the conventional view that dinosaurs owe their name to supposedly negative attributes.

Owen chose his strongly positive label for an excellent reasonâone that could not possibly rank as more ironic today, given our current invocation of dinosaurs as a primary example of the wondrous change and variety that evolution has imparted to the history of life on our planet. In short, Owen selected his positive name in order to use dinosaurs as a focal argument

against

the most popular version of evolutionary theory in the 1840s. Owen's refutation of evolutionâand his invocation of newly minted dinosaurs as a primary exampleâ forms the climax and central point in his concluding section of a two-volume report on British fossil reptiles (entided “Summary,” and occupying pages 191-204 of the 1842 publication).

This ironic tale about the origin of dinosaurs as a weapon against evolution holds sufficient interest for its own immediate cast of characters (involving, in equal measure, the.most important scientists of the day, and the fossils deemed most fascinating by posterity). But the story gains even more significance by illustrating a key principle in the history of science. All major discoveries suffer from simplistic “creation myths” or “eureka stories”âthat is, tales about momentary flashes of brilliantly blinding insight by great thinkers. Such stories fuel one of the primal legends of our cultureâthe lonely persecuted hero, armed with a sword of truth and eventually prevailing against seemingly insuperable odds. These sagas presumably originate (and stubbornly persist against contrary evidence) because we so strongly want them to be true.

Well, sudden conversions and scales falling from eyes may work for religious epiphanies, as in the defining tale about Saul of Tarsus (subsequently renamed Paul the Apostle) on the Damascus Road:“And as he journeyed, he came near Damascus: and suddenly there shined round about him a light from heaven: And he fell to the earth, and heard a voice saying unto him, Saul, Saul, why per-secutest thou me?⦠And immediately there fell from his eyes as it had been

scales; and he received sight forthwith, and arose, and was baptized”

*

(Acts 9:4). But scientific discoveries are deep, difficult, and complex. They require a rejection of one view of reality (never an easy task, either conceptually or psychologically), in favor of a radically new order, teeming with consequences for everything held precious. One doesn't discard the comfort and foundation of a lifetime so lighdy or suddenly. Moreover, even if one thinker experiences an emotional and transforming eureka, he must still work out an elaborate argument, and gather extensive empirical support, to persuade a community of colleagues often stubbornly committed to opposite views. Science, after all, operates both as a social enterprise and an intellectual adventure.

A prominent eureka myth holds that Charles Darwin invented evolution within the lonely genius of his own mind, abetted by personal observations made while he lived on a tiny ship circumnavigating the globe. He then, as the legend continues, dropped the concept like a bombshell on a stunned and shocked world in 1859. Darwin remains my personal hero, and

The Origin of Species

will always be my favorite bookâbut Darwin didn't invent evolution and would never have persuaded an entire intellectual community without substantial priming from generations of earlier evolutionists (including his own grandfather).These forebears prepared the ground, but never devised a plausible mechanism (as Darwin achieved with the principle of natural selection), and they never recorded, or even knew how to recognize,enough supporting documentation.

We can make a general case against such eureka myths as Darwin's epiphany, but such statements carry no credibility without historical counterexamples. If we can show that evolution inspired substantial debate among biologists long before Darwin's publication, then we obtain a primary case for interesting and extended complexity in the anatomy of an intellectual revolution. Historians have developed many such examples (and pre-Darwinian evolutionism has long been a popular subject among scholars),but the eureka myth persists, perhaps because we so yearn to place a name and a date upon defining episodes in our history. I know of no better example, however little known and poorly documented, than Owen's invention of the name

dinosaur

as an explicit weaponâironically for the wrong side, in our current and irrelevant judgmentâin an intense and public debate about the status of evolution.