The Lying Stones of Marrakech (27 page)

Read The Lying Stones of Marrakech Online

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

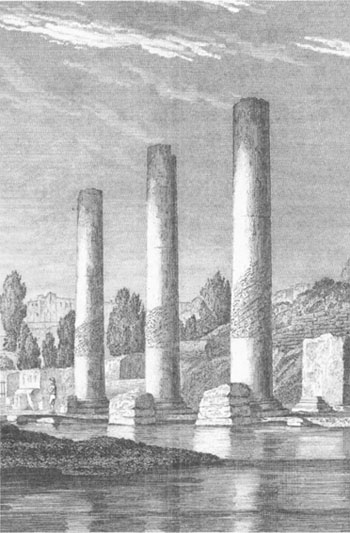

The frontispiece to Lyell's

Principles of Geology,

showing the three pillars of Pozzuoli, with evidence for a substantial rise and fall of sea level in historic times

.

A successful campaign for substantial intellectual reform also requires a new and positive symbol or icon, not just a set of arguments (as presented so far) to refute previous interpretations. Vesuvius in flames, the icon of Pliny or Kircher, must be given a counterweightâsome Neapolitan image, also a consequence of Vesuvian volcanism, to illustrate the efficacy of modern causes and the extensive results produced by accumulating a series of small and gradual changes through substantial time. Lyell therefore chose the Roman pillars of Pozzuoliâ an image that he used as the frontispiece for all editions of

Principles of Geology

(also as an embossed golden figure on the front cover of later editions). By assuming this status as an introductory image in the most famous geological book ever written, the pillars of Pozzuoli became icon numero uno for the earth sciences. I cannot remember ever encountering a modern textbook that does not discuss Lyell's interpretation of these three columns, invariably accompanied by a reproduction of Lyell's original figure, or by an author's snapshot from his own pilgrimage.

II. R

AISING (AND

L

OWERING) THE

C

OLUMNS OF

P

OZZUOLI

In exchanging the pillars of Pozzuoli for the fires of Vesuvius as a Neapolitan symbol for the essence of geological change, Lyell made a brilliant choice and a legitimate interpretation. The three tall columnsâoriginally interpreted as remains of a temple to Serapis (an Egyptian deity much favored by the Romans as well) but now recognized as the entranceway to a marketplaceâhad been buried in later sediment and excavated in 1750. The marble columns, some forty feet tall, are “smooth and uninjured to the height of about twelve feet above their pedestals.” Lyell then made his key observation, clearly illustrated in his frontispiece: “Above this is a zone, about nine feet in height, where the marble has been pierced by a species of marine perforating bivalveâ

Lithodomus.”

From this simple configuration, a wealth of consequences followâall congenial to Lyell's uniformitarian view, and all produced by the same geological agents that shaped the previously reigning icon of Vesuvius in flames. The

columns, obviously, were built above sea level in the first or second century

A.D.

But the entire structure then became partially filled by volcanic debris, and subsequently covered by sea water to a height of twenty feet above the bases of the columns. The nine feet of marine clam holes (the same animals that, as misnamed “shipworms,” burrow into piers, moorings, and hulls of vessels throughout the world) prove that the columns then stood entirely underwater to this levelâfor these clams cannot live above the low-tide line, and the Mediterranean Sea experiences little measurable tide in any case. The nine feet of clam borings, underlain by twelve feet of uninjured column, implies that an infill of volcanic sediments had protected the lower parts of the columnsâfor these clams live only in clear water.

But the bases of the columns now stand at sea levelâso this twenty-foot immersion must have been reversed by a subsequent raising of land nearly to the level of original construction. Thus, in a geological moment of fewer than two thousand years, the “temple of Serapis” experienced at least two major movements of the surrounding countryside (without ever toppling the columns)âmore than twenty feet down, followed by a rise of comparable magnitude. If such geological activity can mark so short a time, how could anyone deny the efficacy of modern causes to render the full panoply of geological history in the hundreds of millions of years actually available? And how could anyone argue that the earth has now become quiescent, after a more fiery youth, if the mere geological moment of historical time can witness so much mobility? Thus, Lyell presented the three pillars of Pozzuoli as a triumphant icon for both key postulates of his uniformitarian systemâthe efficacy of modern causes, and the relative constancy of their magnitude through time.

The notion of a geologist touring Naples, but omitting nearby Pozzuoli, makes about as much sense as a tale of a pilgrim to Mecca who visited the casbah but skipped the Kaaba. Now I admire Lyell enormously as a great thinker and writer, but I have never been a partisan of his uniformitarian views. (My very first scientific paper, published in 1965, identified a logical confusion among Lyell's various definitions of uniformity.) But my own observations of the pillars of Pozzuoli seemed only to strengthen and extend his conclusions on the extent and gradual character of geological change during historical times.

I had brought only the first edition (1830â33) of Lyell's

Principles

with me to Naples. In this original text, Lyell attributed (tentatively, to be sure) all changes in level to just two discrete and rapid events. He correlated the initial subsidence (to a level where marine clams could bore into the marble pillars) to “earthquakes which preceded the eruption of the Solfatara” (a volcanic field

on the outskirts of Pozzuoli) in 1198. “The pumice and other matters ejected from that volcano might have fallen in heavy showers into the sea, and would thus immediately have covered up the lower part of the columns.” Lyell then ascribed the subsequent rise of the pillars to a general swelling and uplift of land that culminated in the formation of Monte Nuovo, a volcanic mound on the outskirts of Pozzuoli, in 1538.

But at the site, I observed, with some surprise, that the evidence for changing levels of land seemed more extended and complex. I noticed the high zone of clam borings on the three columns, but evidenceânot mentioned by Lyellâfor another discrete episode of marine incursion struck me as even more obvious and prominent, and I wondered why I had never read anything about this event. Not only on the three major columns, but on every part of the complex (see the accompanying figure)âthe minor columns at the corners of the quadrangular market area, the series of still smaller columns surrounding a circular area in the middle of the market, and even the brick walls and sides of structures surrounding the quadrangleâI noted a zone, extending two to three feet up from the marble floor of the complex and terminated by a sharp line of demarcation. Within this zone, barnacles and oyster shells remain cemented to the bricks and columnsâso the distinct line on top must represent a previous high-water mark. Thus, the still higher zone of clam borings does not mark the only episode of marine incursion. This lower, but more prominent, zone of shells must signify a later depression of land. But when?

Lyell's original frontispiece (redrafted from an Italian publication of 1820), which includes the bases of the large columns, depicts no evidence for this zone. Did he just fail to see the barnacles and oysters, or did this period of marine flooding occur after 1830? I scoured some antiquarian bookstores in Naples and found several early-nineteenth-century prints of the columns (from travel books about landscapes and antiquities, not from scientific publications). None showed the lower zone of barnacles and oysters. But I did learn something interesting from these prints. None depicted the minor columns now standing both in the circular area at the center, and around the edge of the quadrangleâalthough these locations appear as flat areas strewn with bric-a-brac in some prints. But a later print of 1848 shows columns in the central circular area. I must therefore assume that the excavators of Pozzuoli reerected the smaller columns of the quadrangle and central circle sometime near the middle of the nineteenth centuryâwhile we know that Lyell's three major columns stood upright from their first discovery in 1749. (A fourth major column still lies in several pieces on the marble floor of the complex.)

All these facts point to a coherent conclusion. The minor columns of the central circle and quadrangle include the lower zone of barnacles and oysters. These small columns were not reerected before the mid-nineteenth century. Lyell's frontispiece, and other prints from the early nineteenth century, show the three large columns without encrusting barnacles and oysters at the base. Therefore, this later subsidence of land (or rise of sea to a few feet above modern levels) must have culminated sometime after the 1840sâthus adding further evidence for Lyell's claim of substantial and complex movements of the earth

within

the geological eye-blink of historic times.

For a few days, I thought that I had made at least a minor discovery at Pozzuoliâuntil I returned home (and to reality), and consulted some later editions of Lyell's

Principles

, a book that became his growing and changing child (and his lifelong source of income), reaching a twelfth edition by the time of his death. In fact, Lyell documented, in two major stages, how increasing knowledge about the pillars of Pozzuoli had enriched his uniformitarian view from his initial hypothesis of two quick and discrete changes toward a scenario of more gradual and more frequent alterations of level.

1. In the early 1830s, Charles Babbage, Lyell's colleague and one of the most interesting intellectuals of Victorian Britain (more about him later), made an extensive study of the Pozzuoli columns and concluded that both the major fall of land (to the level of the clam borings) and the subsequent rise had occurred in a complex and protracted manner through several substages, and not all at once as Lyell had originally believed. Lyell wrote in the sixth edition of 1840:

Mr. Babbage, after carefully examining several incrustations ⦠as also the distinct marks of ancient lines of water-level, visible below the zone of lithophagous perforations [holes of boring clams, in plain English], has come to the conclusion, and I think, proved, that the subsidence of the building was not sudden, or at one period only, but gradual, and by successive movements. As to the re-elevation of the depressed tract, that may also have occurred at different periods.

2. When Lyell first visited Pozzuoli in 1828, the high-water level virtually matched the marble pavement. (Most early prints, including Lyell's frontispiece, show minor puddling and flooding of the complex. Later prints, including an 1836 version from Babbage that Lyell adopted as a replacement for his original frontispiece in later editions of

Principles

, tend to depict deeper water.) In 1838, Lyell read a precise account of this modern episode of renewed subsidenceâand

he then monitored this most recent change in subsequent editions of

Principles

. Niccolini, “a learned architect [who] visited the ruins frequently for the sake of making drawings,” found that the complex had sunk about two feet from his first observations in 1807 until 1838, when “fish were caught every day on that part of the pavement where in 1807, there was never a drop of water in calm weather.”

Lyell continued to inquire about this active subsidenceâfrom a British colleague named Smith in 1847, from an Italian named Scacchi in 1852, and from his own observations on a last trip in 1858. Lyell acknowledged several feet of recent sinking and decided to blame the old icon of Vesuvius! The volcano had been active for nearly a hundred years, including some spectacular eruptions during Hamilton's tenure as British ambassadorâafter several centuries of quiescence. Lyell assumed that this current subsidence of surrounding land must represent an adjustment to the loss of so much underground material from the volcano's crater. He wrote: “Vesuvius once more became a most active vent, and has been ever since, and during the same lapse of time the area of the temple, so far as we know anything of its history, has been subsiding.”

In any case, I assume that the prominent layer of encrustation by marine barnacles and oysters, unmentioned by Lyell and undepicted in all my early-nineteenth-century sourcesâbut (to my eyes at least) the most obvious sign of former geological activity at Pozzuoli today, and far more striking, in a purely visual sense, than the higher zone of clam boringsâoccurred during a more recent episode of higher seas. Again, we can only vindicate Lyell's conviction about the continuing efficacy of current geological processes.

A conventional essay in the hagiographical mode would end here, with Lyell triumphant even beyond the grave and his own observations. But strict uniformity, like its old alternative of uncompromising catastrophism, cannot capture all the complexity of a rich and flexible world that says yes to at least part of most honorable extremes in human system building.

Uniformity provided an important alternative and corrective to strict catastrophism, but not the complete truth about a complex earth. Much of nature does proceed in Lyell's slow and nondirectional manner, but genuine global catastrophes have also shaped our planet's historyâan idea once again in vogue, given virtual proof for triggering of the late Cretaceous mass extinction, an event that removed dinosaurs along with some 50 percent of all marine species, by the impact of an extraterrestrial body. Our city of intellectual possibilities includes many mansions, and restriction to one great house will keep us walled off from much of nature's truth.