The Locust and the Bird (33 page)

Read The Locust and the Bird Online

Authors: Hanan Al-Shaykh

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

We said goodbye to her on the seventh day, in the hope of visiting her again during Eid. But she visits us all the time, whether we are awake or asleep, happy or sad. Each one of us has lived to regret something they once said, or didn’t say, to her. But Mother makes us laugh too, especially when we remember her friends arriving at her funeral adorned with generous presents from her, gifts originally given to her by us: one friend with a gold ring; Fadila carrying a snakeskin purse; and Leila a Hermès scarf – because Mother never did like its pattern of horses.

As I said goodbye to her, I thought of what she would have said if she were looking at her own grave.

‘We go up and down; we run hither and thither; we roam here and there and everywhere and we end up exactly where we began. And here I am, back in my place near Muhammad, to be with him for ever.’

Epilogue

M

Y DAUGHTER IS

married, and I feel as if my mother is sitting with me in the limousine, sitting behind my eyes, absorbing the noisy hum of New York. In my mind, she’s wearing her blue-and-white suit, the one she wore whenever she wanted to look ‘chic’, as she used to say.

She scolds me, as I have not managed to buy a new dress for the wedding.

I tell her, ‘How could I when I am mourning you still, with neither the energy nor the will to look my best? I only buried you a month ago.’ I tell her how much I miss her and ask for her forgiveness for not telling her I was getting married thirty-three years earlier, for not sending word to her when I was about to give birth to my children.

She laughs with the bride and groom, and clutches the womb that gave birth to me.

‘Look what my descendants have achieved: from a village in southern Lebanon to New York.’

I whisper to her, ‘Your brave genes are in my blood. You are the source of my strength and independence.’

Two years after my mother died, I sat down to write her story. Majida had sent Muhammad’s diaries and letters to help me. When I wrote, faded sheets, some as yellow as wilted gardenias, were scattered about.

Muhammad had written on school exercise books, pieces of cardboard, government paper and headed paper decorated

with flowers and butterflies from a grand shop in Beirut, which I loved for its Venetian architecture. I felt a rush of nostalgia when I saw it. He wrote in pencil, black and dark-blue ink. Here I was, possessing the years from the thirties to 1960, the year Muhammad died, in his own hand; the lines, the colour of the ink and the pencil made me shiver. I saw my mother in her happiness and in her strife. I listened and heard Muhammad as he moaned, felt his despair, machismo and vanity.

Muhammad wrote full pages, not leaving one inch empty, as if he was writing from prison and paper was scarce. He wrote different poems on each of the eight sides of a folded piece of paper. He wrote plays and stories, three pages’ worth of material on one page. It was as if he hadn’t stopped to take a breath. I listened to his voice, guessed his moods, took his pulse. Love was on Muhammad’s mind and on the mind of his friends and brothers. As I read their letters I saw that men also suffer because of love and betrayal. ‘My love is as strong as rock,’ Muhammad wrote. ‘I love you more than I love life.’ And after he married my mother, he always addressed her as ‘darling wife’.

I found my name in one of his letters to my mother. A cup of coffee had scalded my face at the age of two; Muhammad was concerned, asking after me, wanting to see me. As I read this, I found myself touching my face, with no memory, or trace of a burn. Suddenly he managed to wipe away my jealousy, jealousy that was never stronger than when I once stood at their door after a quarrel with my stepmother. They were grilling kebabs and my mother tried in vain to persuade me to come in; Muhammad pleaded with me, but my feet were nailed to the tiles. I was jealous and felt awkward and clumsy. I wanted to be my baby sister in her pink pyjamas. I wanted to be included in that moment, but I didn’t know how.

On a mangy page torn from a school exercise book I found a letter, addressed to Muhammad in a child’s hand. Had somebody steadied my mother’s hand and helped her to write this letter? As I read it my heart skipped a beat. It was the letter my sister Fatima wrote, as she and Mother hid in the bathroom. Reading it and observing the spelling mistakes and the hesitation of a child filled me with sorrow and regret. Did Fatima feel confused, or proud that she was able to write a letter for an adult?

And then I found a small piece of pale-pink paper with writing in red ink across it. It was my mother’s will, written with Muhammad’s help, signed by her very carefully, letter by letter at the bottom, as if written by a child. She left twelve bracelets to be sold to pay for someone to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca on her behalf; her wedding ring for my sister Ahlam; two sets of earrings, one for me and the other for Fatima; one half of her clothes for me, the other half for Fatima. The sofa, carpet, couches and cupboard were all for Ahlam. The will had been written just two years after her divorce. Had she thought of dying? Was she thinking of ending her own life? I asked around, but no one could give me an answer.

I found an official message from Jean Helio, French High Commissioner to the Lebanese people in 1934, telling them they were to vote to elect the first national assembly for an independent Lebanon, and assuring them that it would be an honest and fair election. On this address Muhammad had poured out his heart in a love letter:

Not a moment passes without my thinking how lonely I am in this life, even though the world may seem to keep it full, and all because I am so far away from you.

The minutes slip by so fast, as I sit here. My eyes sing them songs of emotion and tenderness, and they look at me as if to say, ‘What you see before you is but a version in miniature of what is in my heart, my beloved!’

I have measured the days in terms of our two hearts, each of them filled with a violent passion. My beloved, whom I worship and adore, I have decided to set you apart for a long time, a time when my agony will be dire indeed.

As much as love is poured out on these fragile sheets, death is ever present on the torn and disintegrating paper. The writers, all dead now, speak of dying almost as often as they do of love, but their idealism shines through. This was a generation that believed in politics, in pan-Arabism, in the homeland and independence. Luckily Muhammad was not alive to witness the strife that enveloped Lebanon and still continues; and the exile and disintegration of his beloved family, as his children became immigrants in all corners of the world.

Muhammad touched me deeply as I read and understood how much his existence was tied to the written word. And yet he fell passionately in love with my illiterate mother, embracing with such ease that vividness of hers, which unnerved so many others. How I wished I was their messenger instead of the grocery boy, carrying Muhammad’s heart to her even when he wrote when I was barely one year old, ‘Shall I try to help you get a divorce or are you simply fooling about and passing time?’ And how powerful a thing to have these words left to me, particularly since my mother didn’t write.

The last thing I read was a letter from my mother, dictated to Muhammad Kamal and addressed to me but never sent. It had been written during one of her lengthy visits to Kuwait, after she heard me being interviewed on Lebanese television when I published

The Story of Zahra

:

Don’t measure things by a past that is gone. It was sweet indeed, because I challenged the executioner and the chains that bound my wrists. I regained my freedom from all those virgin maidens who were sold without a price. But fate was stronger than I was, and it crushed me. It took everything I had, absolutely everything. I turned into a tree that had been stripped of all its leaves, leaves that jumped from pavement to pavement in the company of their friends, the breeze and the howling wind. I became a ship with no shore in sight. When I saw your lovely picture and heard the sound of your sweet, melodious voice, I received back my own beauty from yours and my intelligence from yours as well. That stripped tree once again started to sprout gleaming leaves, and they will stay that way just as long as life and capacity stay with me.

The minute I gathered all the papers of our conversations and sessions together, ready to work, my mother became alive, not in Beirut, or in the mountains, or in the south, but this time in my flat in London. She was living her life again for me. I saw her for the first time as a child, a teenager, a young woman, then middle-aged, and finally an old lady. I travelled into another world of emotions, stories, metaphors and anecdotes, sometimes reduced to tears and sometimes roaring with laughter. I was humbled by her frankness, by her courage as she spilled out what was hidden, as if she had lifted the lid of a deep, deep well. When I became too distressed over a certain episode in her life and couldn’t go on, my mother’s photo, which I had stuck on one of the notebooks, would cheer me up. In it, she was accepting a silver cup from an official, after one of my sisters was crowned Queen of Dance at the summer resort party. My mother had rushed over to him and asked him to pretend to give her the cup instead.

The day I started to write her memoir, I could hear protesters outside the nearby Canadian Embassy, demonstrating to save the seals. A tourist bus passed by. I could hear the guide’s words: ‘To your right is the memorial for 9/11, and to your left is the Italian Embassy.’

I caught myself muttering, ‘And here is Hanan, writing about her mother, who loved and suffered, who ran away, who raised her fist against the rules and traditions of the world into which she was born, and who transformed her lies into a lifetime of naked honesty.’

I opened my first chapter with the words, ‘I can see my mother and her brother, my Uncle Kamil, running after my grandfather,’ and then I stopped. Or was it my mother who stopped me? I heard her voice insisting that she wanted to tell her own story. She did not want my voice; she wanted the beat of her own heart, her anxieties and laughter, her dreams and nightmares. She wanted her own voice. She wanted to go back to the beginning. She was ecstatic that at long last she could tell her story. My mother wrote this book. She is the one who spread her wings. I just blew the wind that took her on her long journey back in time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to Margaret Stead, whose help I am ever grateful for.

A NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

Hanan al-Shaykh is one of the contemporary Arab world’s most acclaimed writers. She was born in Lebanon and brought up in Beirut, before going to Cairo to receive her education. She was a successful journalist in Cairo and in Beirut, then later lived in the Arabian Gulf, before moving to London. She is the author of the collection

I Sweep the Sun off Rooftops

and her novels include

The Story of Zahra

,

Women of Sand and Myrrh

,

Beirut Blues

and, most recently,

Only in London

, which was shortlisted for the

Independent

Foreign Fiction Prize. She lives in London.

A NOTE ON THE TRANSLATOR

Roger Allen has taught Arabic literature at the University of Pennsylvania since 1968. He has written numerous general studies on Arabic literature, both modern and pre-modern. He has also edited several specialist journals in the field and translated into English works by many Arab authors, including Naguib Mahfouz.

Translation copyright © 2009 by Hanan al-Shaykh

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random

House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in Lebanon by

Dar Al Adab, Beirut, in 2005. This translation originally published in Great

Britain by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London.

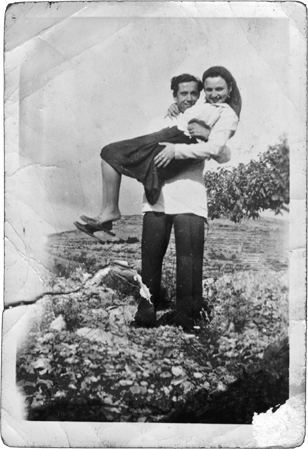

The photograph copyright © Gautier Deblonde/NB Pictures

and reproduced by permission. All other photographs and images are

reproduced courtesy of the author.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaykh, Hanan.

[Hikayati sharhun yatul. English]

The locust and the bird : my mother’s story / Hanan al-Shaykh.

p. cm.

Based on the author’s recordings of her illiterate mother’s narration of

different stages of her life.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37836-1

1. Kamilah, d. 2001. 2. Muslim women—Lebanon—Biography.

3. Shaykh, Hanan—Family. 4. Beirut (Lebanon)—Social life and

customs—20th century. I. Title.

PJ7862.H356Z8713 2009 892.7′8609—dc22 [b] 2008054683