The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (7 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

In spite of the Queen-Mother's condition time seems

to have passed gaily at the provincial town. A grand christening took place, Buckingham standing godfather to the son of the Duchesse de Chaulmes. The event was celebrated by a ball, when Anne outshone all others present—including, one cannot but feel, little Henrietta herself, by rights the central figure of the show—and took every one by surprise by her dazzling beauty. Under these circumstances, to some at least of the royal party, the Queen-Mother's illness may not have been wholly matter of regret. Buckingham's own conduct was ambiguous. Whilst appearing to wish to hasten the journey, he let it be understood that he had orders to await her Majesty's recovery. Altogether, " la maniere d'agir de cet etranger," says Brienne severely, "me deplut beaucoup." This masculine point of view contrasts curiously with that of Madame de Motteville, who learnt the facts from Anne herself. It is evident that, if in her opinion the Queen's heart was not untouched, she had many excuses. Was it surprising, she asks, if Buckingham, with his beautiful face, his great soul, the glamour of the position he occupied in England, and his noble if blameworthy desires, should have had the happiness of obtaining from the Queen the avowal that, had it been possible for a good woman to love any man save her husband, he alone would have been able to win her grace ?

However this might be, it was becoming clear that the situation could not be further prolonged. An intimation to that effect having been given by the Queen-Mother, the Duke made a virtue of necessity and requested permission to resume the journey, Henrietta being apparently consulted by no one on the subject. There was a leave-taking between the Queen and her lover—Anne in her coach and the Duke at the door—

when Buckingham's tears are said to have flowed freely, and the Princesse de Conti, present on the occasion, afterwards observed that, though ready to answer to the King for his wife's virtue, she suspected her at least of pity.

Another parting had likewise taken place—the inevitable separation of Henrietta from her mother. At that last farewell Marie de Medicis placed in her daughter's hands a lengthy epistle, purporting to contain her own final counsels and admonitions. The true author of this document appears to have been the Queen-Mother's confessor, Pere de Berulle, and the paper, of some literary merit and not lacking in a certain eloquence, bears the mark of a hand more practised in the art of composition than that of the Italian Queen. Admirable as are its precepts and its exhortations to the performance of the duties of a wife—principles, one observes in passing, upon which Marie de Medicis' own conduct had been in no wise based—the main object of the writer was clearly to safeguard the fifteen-year-old Queen from influences adverse to her faith, to kindle her to greater religious zeal, and to enlist her sympathies on behalf of the English Catholics. Henrietta is exhorted to mould her conduct upon that of her ancestor St. Louis, and to be, like him, firm and zealous for the Christian religion, in defence of which he exposed his life, dying faithful amongst infidels.

" I must end," concludes a document containing close upon three thousand words. " I must let you go, weeping and praying God to let you know what I am unable to say and what my tears, if I wrote it, would efface. I leave you to the guardianship of God and of His angel. I give you to Christ, our Lord and Redeemer. I implore the Virgin, whose name you bear, VOL. i. 4

to vouchsafe to be the Mother of your soul, as she is the Mother of your God and Saviour. Adieu, once more and many times, adieu. You belong to God. Remain God's for ever."

Thus was Henrietta sent forth into the world to fight her battles for God and for the Church. The sequel leaves no room for doubt that the child took to heart the lessons she had received.

One other event marks this journey. It closes the episode of Anne of Austria's intercourse with George Villiers. The parting witnessed by the Princesse de Conti was not to be their last. The Duke was no man to let his own interest or pleasure wait upon that of a king or of a kingdom. At all costs he determined to see the Queen once again. Making a pretext of urgent business, he therefore left Henrietta at her next halting-place and hurried back to Amiens. Finding the Queen-Mother still confined to her bed, he demanded an interview, transacted the business he had alleged as his excuse, and then requested an audience of her daughter-in-law. Anne, also in bed, and become, a little suddenly, discreet, at first declined to grant his petition—relenting afterwards so far as to send her maid-of-honour, the Comtesse de Lanoy, to ask the Queen-Mother's advice as to whether the " etranger presomptueux" should be accorded the grace he besought.

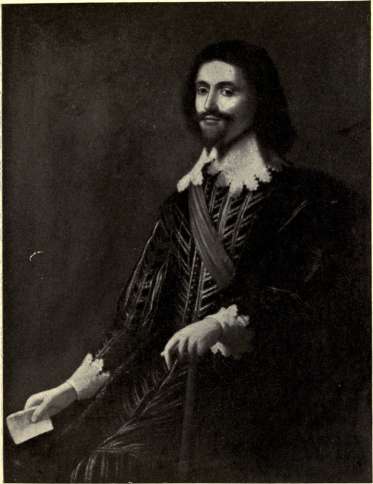

Madame de Lanoy,

After the picture by Gerard Honlhorst in the National Portrait Gallery.

Photo by Emery Walker,

GEORGE VILLIERS, FIRST DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM.

BUCKINGHAM AND QUEEN ANNE 51

asked why, since she herself had granted the Duke an interview, Anne should not do likewise ? Madame de Lanoy, prudently refraining from pointing out the obvious reasons, returned to her mistress, defeated, forced to withdraw her opposition, the wise, virtuous, and aged lady took her measures. Investing the interview with the formality of a state ceremonial, she assembled a miniature court in Anne's bed-chamber; and when Buckingham, disregarding the presence of witnesses and throwing himself on his knees beside the Queen, kissed the bed-coverings, Lanoy requested him to rise and to take the seat to which he was entitled by his rank, explaining severely that the attitude he had assumed was not customary in France. The Duke protested. He was not French, he said, nor compelled to yield obedience to French laws. Then, addressing himself to the Queen, " lui dit tout haut les choses du monde les plus tendres."

The Queen herself had, it appears, hitherto played a passive part in the melodrama. " She did me the honour to say that she was embarrassed," says Madame de Motteville ; and embarrassment, joined to some indignation, kept her at first silent. When she at last spoke, it was to blame the Duke's temerity, and— " though perhaps without overmuch anger "—to order him to rise and leave her.

Thus ended, with the exception of a public leave-taking on the following day, an episode fraught, in the opinion of most historians, with momentous consequences. The Duke had effectually barred his way to a return to France. On three separate occasions the French authorities were explicit in their refusal to receive him as ambassador. It remained, if his parting with Anne at Amiens was not to prove final, for him to force

his way to Paris in the character of an enemy. To this end it is believed that his future policy was directed. What that policy was is well known. For the present he returned to his duty of escorting Henrietta to England.

CHAPTER III

1625—1626

Henrietta's arrival in England—Meeting with Charles—Religious and domestic difficulties—Charles' first Parliament—Dissensions in the royal household—Buckingham's hostility—He is declined as envoy to Paris—Charles' complaints of his wife—He resolves to dismiss her French attendants.

'THHE arrival of the young Queen in England did not, _L after all, take place till towards the end of June. Her meeting with the King, as well as the opening scenes of their life together, are described in detail by authorities French and English. It is curious to compare the different interpretations placed upon each incident according to the bias of the chronicler.

The Comte de Tillieres and his wife were attached to Henrietta's household, and the ex-ambassador, in his character of chamberlain, has left an exhaustive account of the slights he conceives to have been put upon the bride and her train. His complaints must be accepted with reservation, but though naturally prejudiced in his mistress's favour, so far as the disputes between herself and the King are concerned, he would appear to have been an honest man. Nor would he have had any temptation to make it appear that the marriage for which he had laboured so industriously was likely to prove a failure. Punctilious on matters of etiquette he undoubtedly was ; and the very departures from rigid conventionality commending themselves to the spirit of romance evidenced by

S3

Charles' Spanish expedition, would be regarded by his wife's chamberlain as lacking in respect to the bride.

It should be borne in mind that the two chief actors in the drama now beginning were little more than boy and girl : that Henrietta was a spoilt child of fifteen, a stranger in a foreign land, and not inexcusably disposed to cling with unwise tenacity to all that savoured of the life she had left behind her ; whilst Charles, the two-months King, entertained pronounced notions of a husband's authority, and was young enough not to make due allowance for the petulant wilfulness of the lonely child committed to his care. In matters of religion he had already given unmistakable proofs of the strength of the prejudice entertained by him against his wife's faith. One of his initial measures as King had been to give orders that no recusant Papist, of what rank soever, should be provided with mourning ; whilst a court gossip adds that not only had the High Sheriff of Nottingham been deprived of his office in consequence of his having left the judges at the door of the Protestant church, but that, furthermore, a certain Irish earl had received his dismissal from court owing to his refusal to attend the King's devotions. " If he will not come to my prayers," said Charles, "let him get out of my house." The frame of mind thus indicated was scarcely such as to incline him to look with a favourable eye upon the train of bishops, priests, and lay Catholics, masculine and feminine, by whom his wife came attended.

By a comparison of the French and English accounts it is possible to gain a fairly clear impression of the first days spent by Henrietta in England, supplying the key to much that followed.

The salvos of artillery announcing the embarkation at Boulogne of the Queen and her escort, did not find

King Charles at Dover. He had indeed resorted thither some weeks earlier, when the arrival of his bride had been expected to take place at once ; but repeated delays had wearied him out, and he had withdrawn to join the expectant court at Canterbury. His impatience had been fully shared by his subjects.

" We do very little here," says a news-letter from London, *' but expect the Queen's coming and marvel it is so long deferred. The lords and ladies waiting for her at Canterbury are in great trouble and chagrin. But the King cheers them up almost every day with messages from Dover, and persuades them to patience."

On June 2Oth Henrietta was reported to have reached Boulogne, a letter written on that day by the Mayor of Dover to Lord Conway serving to emphasise the youth of the traveller. News had been brought by a mariner of her arrival at the French seaport about five o'clock on the previous afternoon, when the man himself had seen her viewing the sea at such close quarters that it had been bold to kiss her feet. Her Majesty had indeed been over-shoes, returning from the shore with great pleasure.

Charles himself was at Canterbury when a messenger, riding very swiftly, brought tidings that the Queen had at length landed upon English soil. It is said that it was in deference to her mother's expressed wishes that he put off the meeting with his bride until she should have had time to recover from the effects of her first sea-voyage ; but the thoughtfulness of mother and husband alike was probably misplaced, and the absence of a welcome must have struck Henrietta coldly. Nor did the arrangements made for her reception at Dover find favour in the eyes of her chamberlain. The castle was " un vieux batiment fait a 1'antique'' ; the

Queen was ill lodged, and her apartments badly furnished. 1 There was a total absence of that splendour represented by the ambassadors as awaiting her in England ; and it was, perhaps, scarcely to be wondered at that, fresh from the gorgeous Parisian fetes in her honour, Henrietta should have experienced a chilling sense of disappointment.

By ten o'clock the next morning Charles had reached the castle. Breakfast was proceeding, but disregarding the King's suggestion that it should not be interrupted, Henrietta rose hastily from the table upon hearing of his arrival, and, running downstairs to meet him, would have knelt to kiss his hand, had he not instead " wrapt her up in his arms with many kisses." She had, however, been too well primed in her part not to attempt the little set speech with which she had come prepared.

" Sire," she began, " I am come to this country of your Majesty's to be made use of and commanded by you ;" but before she could proceed further, nervousness and excitement had got the upper hand and she broke into a passion of tears.

Charles—not, one imagines, without some masculine dismay—led her into an inner chamber, and, with more kisses, did his best to soothe her. Finding her, to use the language of an old biographer, " somewhat surprised " at her position as the bride of a bridegroom hitherto unknown, he set himself to reassure her. She was not fallen, he said, into the hands of enemies and strangers ; it was God's will that she