The life of Queen Henrietta Maria (26 page)

Read The life of Queen Henrietta Maria Online

Authors: Ida A. (Ida Ashworth) Taylor

Tags: #Henrietta Maria, Queen, consort of Charles I, King of England, 1609-1669

her hand and taking no one into her confidence, repaired evening after evening, for the purpose of meeting them and of making, though in vain, every offer in her power." l It must soon, however, have been clear that, unless the King had strength enough to save him, the fate of his minister was sealed.

The trial was opened on March 22nd. From a tribune prepared for them the King and Queen looked down upon the scene. Charles, with his own hands, had torn down the lattice obstructing their view, and day after day they were present at the proceedings, never, as Henrietta afterwards said, leaving the hall, " que le coeur saisi de douleur, et leurs yeux pleins de larmes." There is no reason to doubt the Queen's sincerity, or to underrate her strenuous desire to avert the doom of the man she now regarded as her husband's most faithful servant. But her zeal was not according to knowledge, and it may easily be that her partisanship proved more fatal to the Earl than her enmity. It was a moment when the dislike she had once felt for him might have turned to his advantage in the eyes of his enemies ; but she made no secret of the opposite nature of her present sentiments. "The Queen," wrote Strafford himself towards the end, " is infinitely gracious towards me, above all that you can imagine, and doth declare it in a very public and strange manner, so as nothing can hurt me, by God's help, but the iniquity and necessity of these times."

If it was difficult for Henrietta to realise that the favour men had formerly eagerly sought was likely to turn to the ruin of the man to whom she displayed

1 The Queen's account has not always carried conviction ; nor is it improbable that, in giving it, memory found an auxiliary in imagination. But she doubtless did her utmost to save the Earl.

HENRIETTA MARIA

it, the schemes to which she was ready to lend her ear were not less calculated to damn him. Her enemies can scarcely have been ignorant of her attempts to obtain foreign assistance for the King, futile though such attempts had proved. It was, however, plain that, for the present, the means of opposing resistance to Parliament must be sought within, rather than without, the kingdom ; and to the army, already in a promising state of discontent at its treatment by the popular leaders, the eyes of the King's partisans were turning.

From this body they indulged the hope of securing a force strong enough to counterbalance the power wielded by the House of Commons. The outcome of this hope, known by the name of the Army Plot, consisted of two separate schemes, each taking shape independently of the other. On the one hand, four members of Parliament, Henry Percy, Wilmot, Pollard, and Ash-burnham, holding commissions in the army, had developed a plan for utilising the dissatisfaction prevailing amongst the troops, and inducing them to hold themselves ready, in case of need, to lend their support to'.the King in his resistance to any extreme measures at Westminster. Whether or not the project would have had any chance of ultimate success, such chance was materially lessened by the fact that, almost simultaneously, a second plot had been hatched, Sir John Suckling, Henry Jermyn, and George Goring being its chief movers. According to this scheme, far more violent and rash than the first, Goring was to be placed in practical command of the northern army; the troops were to be marched upon London ; the Tower was to be seized, Strafford liberated, and the King freed from the domination of Parliament.

To this last project Charles was from the first opposed. To the other it seems that he lent a dubious though

not unwilling ear. But it was certain that, unless the promoters of each could be brought to agree upon concerted action, neither could succeed. The account of the matter contained in the Queen's narrative, though confused and inaccurate, supplies graphic touches not to be found elsewhere. Whilst the rasher conspirators had made her their confidant, Percy and his friends had communicated their designs to the King. Upon consultation between herself and Charles it was decided that an attempt must be made to induce the rival leaders, represented by Henrietta to be Goring and Wilmot, to cooperate in a common scheme. At Charles' suggestion it was arranged that Jermyn, as the friend of both, should act as intermediary. Reconsidering the question, however, it appeared to Henrietta that the risk he would thereby run was too great; that discovery would result in the necessity of his own flight, as well as that of his friends ; and that she and the King would be thereby left with none upon whom it was possible to rely. To Jermyn she explained her change of view, forbidding him to intervene in the affair, and undertaking to justify him to the King.

It was at this moment that Charles, entering the cabinet in which the interview had taken place, overheard her last words. Repeating them with a laugh, he added :

" Nevertheless, he will do it."

" He will not do it," returned the Queen, also in jest; " and when I shall have told you what it is, I am sure you will be of my opinion."

" Speak then, Madame," replied Charles, " that I may know what it is that I command and you forbid."

Though it was ultimately decided that the risk must be run, no good result followed upon Jermyn's endeavours

to induce the two parties to co-operate ; and Goring, perceiving that neither his ambition nor his interest would be served by participation in the scheme, took the step of betraying it to the Parliamentary leaders. He was thereupon directed to retire to Portsmouth, of which place he was Governor, no immediate action being taken in regard to his disclosures. By the first week in May the Queen's forebodings had been realised, and Jermyn, Percy, and the rest of those concerned in the plot had fled the country. " Colonel Goring," wrote a correspondent to Sir John Pennington when the treachery became known,

To Strafford the scheme was calculated to be more fatal than to any of those directly concerned in it. Unconnected with the plot as he was, it can scarcely have failed to have taken effect upon the great trial going forward at the time.

A chief article in the indictment had dealt with his alleged intention to bring over Irish troops to England ; and the design, now come to light, of employing the northern army to support the King in opposition to Parliament, must have lent no little additional weight and significance to the charge. So far, it is true, the discovery had not been made public; but the chief wire-pullers in both Houses were well aware of the actual state of things. The Earl of Northumberland—a man singled out by Charles for special favour ; whom, to use his own words, he had " courted as his mistress and

1 As an example of the confusion of dates in the Queen's narrative, it may be mentioned that she makes Charles sign Strafford's death-warrant only three days after Goring's treason. In point of fact, Goring's disclosures were made on April 1st, while Charles' signature was not affixed till May gth.

PARLIAMENTARY COURT PLANS 225

conversed with as his friend "—had made, as his sister was presently to do, return for his master's trust by the production of an incriminating letter from his brother, Henry Percy, either in hiding or beyond seas. Nor can there be a doubt that each fresh proof of the plans which had been formed must have rendered those in possession of them more and more keenly alive to the necessity of putting a final end to the chances of the prisoner's regaining a hold upon the military resources of the kingdom. Had it been possible to place confidence in Charles' promise that the Earl should never again be employed in the public service, he might have escaped with life ; but such a pledge, the manifest result of coercion, could scarcely be expected to carry weight ; and the Parliamentary leaders were bent upon making all sure. a Stone-dead hath no fellow," was Essex's grim reply, when Hyde would have pressed upon him more merciful alternatives.

Communication was meanwhile kept up between court and army; and, still ignorant of Goring's betrayal, Portsmouth was regarded by the first as a place of refuge in case of necessity. As the excitement within and without the palace grew and intensified, plan succeeded plan in the royal household, many of them originating in Henrietta's busy and restless brain. The possibility of bringing military aid into England by way of Portsmouth was under consideration. The Irish troops formed another asset in the calculations of the court. An alliance had been formed with Holland which it seemed possible might result in practical aid. On Sunday, May 2nd, the nine-year-old Princess Mary was married to her boy-bridegroom, William of Orange. His union with an English princess had been for some time under consideration, but when the King's affairs VOL. i. 15

had been in a more prosperous condition it had been proposed in England to substitute for Charles' elder daughter her little sister Elizabeth. " The States seek to get my eldest niece," wrote the Queen of Bohemia to Roe, " but that, I hope, willj not be granted : it is too low for her." Her son, who considered himself a more fitting match for Mary, also interfered in the matter, objecting to the anticipated condition that Elizabeth should be brought up in Holland. " Methinks," he had written the previous November, " it is great sauciness in them to demand the breeding of so great a King's daughter."

All was now changed, and the Dutch alliance, on the terms demanded, with Mary as bride, was not to be despised. The young Prince of Orange had come over to England, bringing with him, it was rumoured, a large sum of money ; and in the midst of the anxiety and trouble surrounding the royal household and overshadowing present and future, the ceremony deciding the fate of the King's little daughter took place. It must, under the circumstances, have been but a melancholy affair—an element of family dissension being added by the refusal of the bride's cousin, the Prince Palatine, to assist at the banquet celebrating an event in which he would himself have liked to play the principal part. Henrietta, writing to her sister on the subject, hoped her child would be happy. The husband chosen for her was not a king ; but she was, she added, learning well that it is not kingdoms that give contentment, and that kings are not less unhappy—sometimes even more so—than others.

On the very day when the wedding took place an ill-advised attempt had been made by Charles to introduce a body of soldiers, ostensibly intended for

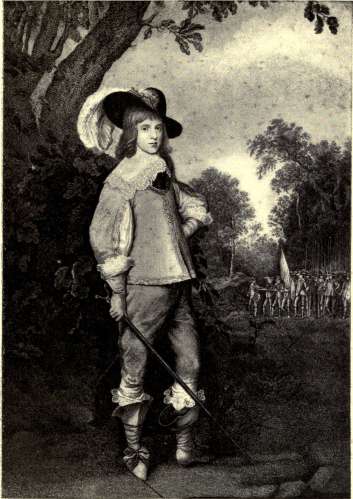

From a painting by Gerard Honthorst at Windsor Castle.

WILLIAM OF NASSAU, PRINCE OF ORANGE.

service in Holland, into the Tower. The plan was frustrated by the refusal of the Lieutenant to admit them ; and the report he made of the matter did not tend to reassure the House of Commons as to the King's intentions. Rumours of French interference—unlikely enough to be true—were likewise afloat, and London was in an uproar. In view of the hostile demonstrations, fresh plans of evasion were evolved at Whitehall. The removal of the Queen—the principal object of public mistrust—to Hampton Court was mooted, and Hampton Court would have been merely a stage on the road to Portsmouth.

On May 5th Pym played the important card he had hitherto held in reserve, by making known the plot revealed by Goring. It was openly stated that persons about the Queen were implicated in it. It was known that she herself was concerned in the scheme. Under the circumstances, the House determined to move her " to stay her journey, for the security of her person, her Majesty not knowing what danger she might be exposed to in those parts" ; whilst the King was requested to forbid his servants to leave London, without his own permission, endorsed by Parliament. By May 6th it had become known that precautions had been taken too late. Jermyn, Percy, and Suckling had already made good their escape. If the Queen's account of the matter is to be credited, though again marked by complete confusion in point of time, Jermyn, having fled to Portsmouth, proceeded to warn Goring, most unnecessarily, of the discovery of the plot in which both had been implicated : when the traitor, " le regardant avec douleur," made confession of his share in the transaction ; and likewise repaired his fault, so far, at least, as Jermyn was concerned, by disobeying the orders

sent him by Parliament to arrest the fugitive, and assisting him to make his escape to France.

If the three chief conspirators had succeeded in eluding pursuit, the Queen was still at Whitehall. To the request preferred by Parliament that she would remain there, she replied with her accustomed spirit. She was her father's daughter, Henrietta said. He had not known how to fly, nor was she about to learn that lesson. The Commons, at any rate, had no intention of allowing her the opportunity of putting it into practice.

In the meantime, every fresh incident, as it became public property, was an additional prejudice to Straffbrd's chances, such as they were, of life. It was soon apparent that Charles alone, the master he had served, stood between the prisoner and the fate awaiting him. So late as April 23rd, the King, in his memorable letter, had assured the Earl that, " upon the word of a king, he should not suffer in life, honour, or fortune." Charles, as well as Strafford, was soon to learn the bitter lesson how weak a guarantee the word of a king may prove. On May 4th the doomed man had written to release his master from the pledge he had voluntarily given. By his own consent to die he had "set his Majesty's conscience at liberty." Four days later the Bill of Attainder had passed, and was awaiting Charles* signature. On that day London was shaken by a fresh wave of excitement. The report of the presence of a French fleet in the Channel had roused the city to frenzy. The Tower was spoken of as a fit lodging for King and Queen ; and Henrietta, in spite of her disclaimer of any intention of flight, was on the point of starting for Portsmouth, until dissuaded from so rash a step by the representations of her brother's ambassador. No calumny was too foul to use in