The Legend of Jesse Smoke (5 page)

Read The Legend of Jesse Smoke Online

Authors: Robert Bausch

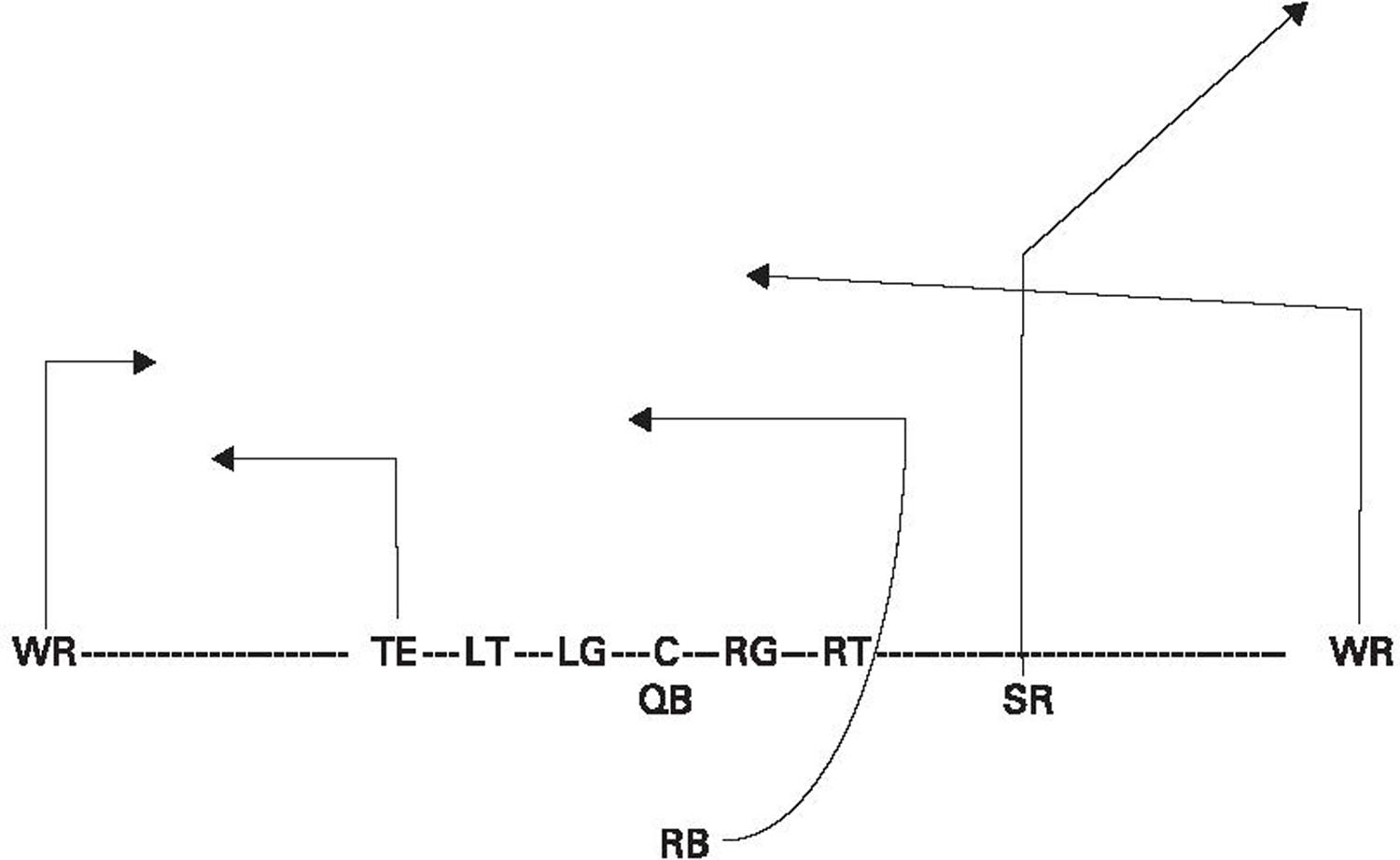

On most plays there are five men on offense the quarterback can throw to: two wide receivers, two running backs, and a tight end. With the above play, there is only one running back and three wide receivers, the two on the outside lined up on the line of scrimmage and the slot receiver.

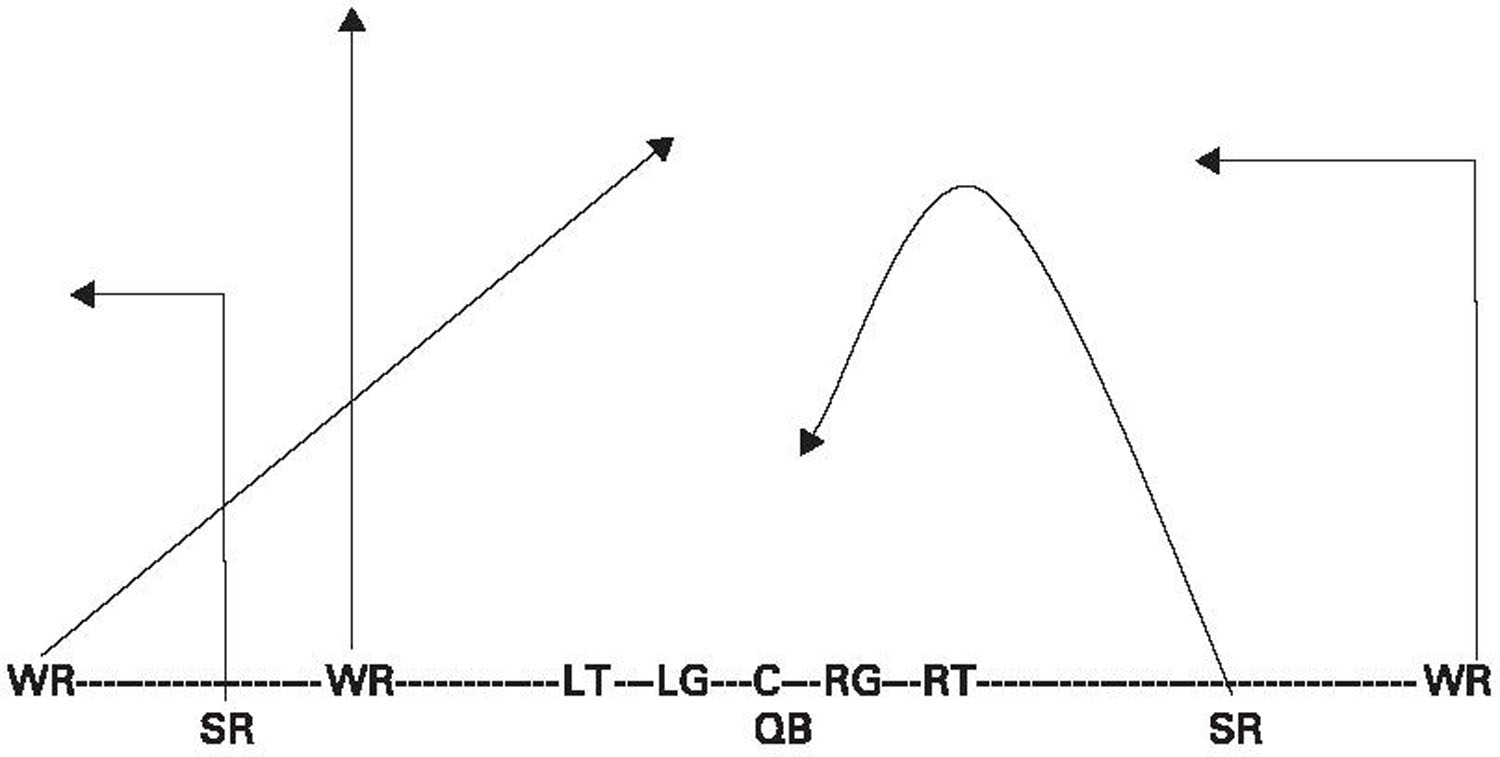

In four-wide-receiver sets, there is no running back, but an extra slot receiver who would line up on the left and parallel to the slot receiver on the other side. In a five-wide-receiver set, teams take out the tight end and split a wide receiver out five yards or so from the line like this:

What you see here are individual plays, with one of the moves on the passing tree assigned to each player. When the quarterback calls a play like this, he knows each of these paths or routes that his receivers will run. And when there are four or five wide receivers, the defense puts in extra defensive backs and takes out linebackers.

That is, very simply, how it works. Now remember, each of these is one play, and there are hundreds of plays, all predicated on the single moves possible in each receiver’s passing tree. Each of the receivers in the plays above, according to the design of each particular play, must make one of the moves on the passing tree. It just depends on which play the quarterback has called.

Above all, the quarterback’s got to release the ball quickly, once he knows where he’s going with it. All of this he’s got to do in less than four seconds, while men twice his size are fighting furiously to get to him and knock him down. When a quarterback can do all these things with absolute calm, without dancing on his feet, or “stuttering” as some coaches call it, and throw the ball exactly as the situation demands—either lofting it gently and letting it fall softly over a receiver’s shoulder and into his hands as he runs, or firing it on a line, with almost no arch in its trajectory whatsoever, to an instantaneously selected spot on the field no larger than the hole in a tire, so that a receiver running full speed runs into it precisely as

he turns, and snatches it out of the air—then, well then you’ve got something.

Those quarterbacks of the past who called their own plays, who planned an offensive strategy while they were doing everything else; who adapted to the game as it developed and altered their play calling to suit the situation on the field—they had to have been geniuses. I know I couldn’t do it. Coach Engram is one of the most intelligent men I’ve ever met, and he never did it.

Far as I know, not one single person who has written a book on Jesse has ever

seen

a women’s game. Well, I went to every Divas game I could that spring. They were all at night, these games—under very poor lights with fewer than a thousand fans watching. The girls had old, discarded high school equipment, but the jerseys and helmets were new, so they looked more or less like a team. But they were slow, too. I have to admit that. Jesse moved around in the pocket, though, like a pro: She read the field, saw receivers, and easily flipped the ball over defenders into their arms. When she was hurried or flushed out of the pocket, she showed that she could throw on the run. She was never terribly rattled.

I noticed just one weakness. In a game against the Philadelphia Fillies—who were tougher and faster than any other team she faced—she started throwing off her back foot as she fell away from the pass rush. That’s a bad habit. She could still throw fairly accurately that way, and remember she was always taking something off the ball—I

mean she wasn’t ever trying to throw very hard, so it wouldn’t hurt her arm to be doing that a few times—but if she let it become habit, and then kept doing that when she

was

trying to throw hard, it would ruin her perfect form, to say nothing of her arm.

I hung around after each game to talk to her. Sometimes the four of us—Jesse; her coach, Andy; Nate; and I—would go get something to eat downtown. I always paid for dinner. That night she played the Fillies was a hard time for all of us. Bigger and faster than the Divas, the Fillies didn’t throw the ball much. All they did was run it, really, up the gut. Play after play. They had a huge offensive line—women who could probably play college ball—and they just pushed their way down the field. They kicked to the Divas and Jesse started a pretty good march down the field with a few passing plays, but then she got sacked for a ten-yard loss and the Divas had to punt. The Fillies used up the entire first quarter to score one touchdown. Jesse drove the Divas down the field in five plays and threw a 15-yard touchdown pass to her favorite target—a tall, lean, bony young woman named Michelle Cloud.

But when they kicked it back to the Fillies, the Divas didn’t see the ball on offense again in the first half. Starting at their 18-yard line, the Fillies drove the ball downfield in eighteen small-yardage running plays and scored another touchdown just before the half.

The Divas had to kick it to the Fillies to start the second half, and it was all over after that. The Fillies took it down the field again, bulling their way in for another touchdown, and even though Jesse hit Michelle with a 45-yard bomb and another touchdown, the Divas could not stop the Fillies’ offense. Their kicker made every extra point, while the Divas missed one, leading to a final score of 28 to 20.

At dinner everybody was a little down. The Fillies, big and clumsy as they were, should not have bullied the Divas so completely. At least that’s what Coach Andy said. “We’ve got so much more finesse than they have.”

“I thought we’d have time to come back,” Nate said. He always talked about the team that way, as if he’d been right on the field beside

them. Of course, most football fans do that. “We’ll get them next time,” they say. It’s always a game “we” play, fans and players alike.

Jesse herself was not too glum. She always seemed to maintain the most even disposition, like an airplane that flies above the storms. She had cut her hair pretty short for the season, and it stuck up now a bit in the back. She wore no makeup, but she didn’t really need it with those naturally dark eyebrows arching perfectly over her deep-set blue eyes. Her lips, too, were naturally red tinted. I already mentioned the brown freckles that ran across her lovely broad nose. And when she smiled, her cheeks themselves seemed to light up.

In the fourth quarter of the game, when the score was 28 to 14, she drove the Divas down the field with a series of short, quick passes. (The Fillies, having wised up to Michelle, always had two defenders following her now at all times.) Finally realizing the drive was taking too much time, Jesse decided to try one last deep pass. She wanted to go to the other wide receiver, Brenda Smalls, who could catch the ball nearly as well as Michelle, though she was not as tall or fast. She might have gotten open, too, but the play took too long to develop, and before Jesse could let the ball fly, a big defensive end knocked her flat on her back. I saw her head bounce off the turf. She rolled over and seemed to stare at the ground a few inches from her nose, then she got herself back up, and though she was a little wobbly, went back to the huddle and called the next play. I could see she had a bloody lip. The defender had put her helmet right under Jesse’s chin and driven her to the ground. It was a miracle she hadn’t fumbled.

Now, at dinner, she seemed a bit groggy. I asked her if she was all right.

“I’m fine.”

“You took a good hit there near the end.”

“I’m all right,” she said. “Really. Bumped my head. That’s it.”

All of them wanted to know what was going on with the Redskins, how the preparations for the new season were going. I’d been working ten hours a day, watching film and grading players, both ours and the

ones from other teams we might be interested in. I scouted players being phased out or in danger of being cut by other teams; I even paid attention to players who might want to make a move through free agency the following year. I studied films of college players who’d not been drafted. We were always looking for new talent.

My job, though, involved finding offensive players. If I happened to notice a guy playing great defense against the people I was looking at, then I’d let somebody on the defensive side know, of course. We were also evaluating our playbook, looking at film from last year’s games and grading those plays that worked most smoothly and the ones that had a higher percentage of screwups.

Nothing is more continually evaluated, designed, and redesigned than an NFL team. Trust me. Nothing on earth. Not even the most complex surgical unit goes under so much self-examination and retooling as we do. And now, almost nothing is more expensive. The annual payroll of the average NFL team would supply the entire U.S. Army.

Anyway, I told them a little of what I was doing, and then tried to turn the conversation back to the game. I wanted to see what Jesse thought about losing; how it affected her.

Nate made a few remarks about how great she had played, completing 14 of 18 passes and throwing for 3 touchdowns. He was amazed by how well she stood up to the pass rush. Then he began talking about how tough the Fillies were.

“It’s always either you guys or the Fillies, isn’t it?” I said to Andy.

“The Cleveland Bombers are tough, too. But yeah. It’s going to be between the Fillies and us. Their coach is a woman, too.”

“Does that make a difference?” I said.

“No,” said Jesse.

“They play a different kind of game, though, don’t they,” I said. “What’d they throw, two passes all day?”

“Three,” Nate said. “I counted ’em.”

“And they completed all three of them,” Jesse said.

“Something’s good about that brand of football,” I said. It was true, of course. As anybody who follows the game knows, if you’ve got the ball on offense and you can keep it a long time, the defense gets tired, time begins to run out. And if you can score at the end of a long drive, it takes something out of the other team; they get the idea they can’t possibly stop you.

“Our defense played pretty well,” Andy said. “They fought it out. Just the Fillies play like men.”

Jesse looked at him.

“I mean—sorry. I didn’t mean that the way it sounded.”

“You’ll get a chance to play them again,” I said to Jesse, “if you make the playoffs.”

“If I had a choice about it,” she said, calmly, “I’d line up on the field right now and play them again.”

“That’s the spirit,” Andy said.

That was the spirit all right. He had no idea what it meant to hear her talk like that. She may have been on the losing side, but she was absolutely undefeated.

Even that early on, I wanted to spend as much time as possible watching Jesse. I wanted to get to know her better than you generally want to know even a top prospect. What kept going through my mind was,

What if she really has what it takes?

Without ever really making a choice one way or the other, I was getting more and more serious about her. She seemed to like me, although she was not particularly open about anything other than football.

I only saw her play in four games, and except for the loss to the Fillies, the others were a breeze. She threw seven touchdown passes against the Baltimore Beauties. Six against the Pittsburgh Bombshells. Not once did I see her lose her cool. The only time she faced any real pressure and got hit hard, she got back up and kept playing. But even in that game she hadn’t allowed herself to be

pushed too much. She could get rid of the ball so fast, a pass rush couldn’t agitate her.

She did start throwing off her back foot against the Fillies, like I said, but the next time I saw her play she stepped into each throw as perfectly as always. Still, I was worried about that little kink in her delivery, because against a real pass rush it would be the end of her. I wondered what I should do about it.

I knew if I brought her to camp and let Engram see her throw, he’d be impressed. But what then? I realized I was worried about how she would do in camp. Not for the little joke I wanted to play, but because I was beginning to see that she really was a damn good football player. But when Coach Engram saw her against the men—against that massive charge of flesh and bone—she absolutely could not fall away from it and throw the ball. They’d spot it in an instant and that would be that. Rather than try to work with her, they might laugh. A man, they’d work with—they’d drill him and strive through practice and repetition to get the kinks worked out. A woman, though, would be a different animal altogether. To win Engram over the way I was won over, she had to be perfect already, in every possible circumstance of the position. Even then, thinking about all these things, I insisted to myself that it was only a joke I wanted to pull; a shock to the system of some of the more comfortable fellows in camp.