The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat (31 page)

Read The Last Stand of Fox Company: A True Story of U.S. Marines in Combat Online

Authors: Bob Drury,Tom Clavin

"With our trucks and artillery, the enemy assumes we're roadbound," he said.

Davis nodded. He was standing over Litzenberg, who was unfurling an old Japanese map.

Litzenberg said, "We have a good chance of catching him by surprise with an overland move."

Davis's head moved almost imperceptibly.

"I want you to work up a plan to do just that and bring it back as soon as you can. We've got to get going on this."

Davis glanced up from the map and nodded again.

Ray Davis may not have been a man of many words, but Litzenberg considered him far and away his most ferocious battalion commander. He needed such a warrior right now. Contradictory orders were flying into Yudam-ni-the Chosin garrison had actually been instructed by the Army's General Almond to break west eighty miles to attack the flank of the Chinese who were destroying the hapless Eighth Army after Litzenberg received orders from the Marines' General Smith to attack southward toward Hagaru-ri- but Litzenberg had plans of his own. The foremost involved this steely, hawk-nosed Georgian who, one fellow officer noted, would look as natural in bib overalls as in dress blues.

Davis was tall and laconic, a graduate of Georgia Tech who carried himself with an unassuming countenance that concealed a combat readiness not found in every officer, or even in every Marine officer. Davis liked to tell friends, "Above all, I see myself as a man of action." He was among the rare military men who relied on neither gruffness nor bluff to inspire their charges, but instead on his poise at the center of any fray. This was an attribute that early on caught the attention of the notoriously belligerent Marine Colonel Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller, who had trained Davis at basic school.

Davis's war experience went back to World War II, in which he had led Marine units against the Japanese across Guadalcanal, New Guinea, and New Britain. His skill as a leader increased with his rank, and as a major in late 1944 he had commanded a Marine battalion at Peleliu, one of the most vicious of coral island campaigns. He had been shot during the first minutes of the landings at Peleliu, but he refused to abandon his command. When a Japanese banzai charge shattered his outfit's defensive lines, he personally led the counterattack despite his leg wound. For this act of bravery he was awarded the Navy Cross. In the summer of 1950, remembering the kid from basic who had shown such leadership qualities, Puller handed Davis his first frontline rifle battalion and told him to report to Colonel Litzenberg in California and prepare for Korea.

Davis had been serving as the inspector-instructor of a reserve battalion in Chicago when Puller tapped him. He accompanied his men by train to Camp Pendleton and was dismayed when, upon arrival, his unit was abruptly disbanded and randomly assigned to various other battalions. Davis resented how his "family" had been broken apart in that predawn episode.

After a few days in California, however, mostly he went about the business, in military parlance, of standing up Litzenberg's First Rifle Battalion. This included not only stopping his Jeep near every work detail or idle group of Marines to shanghai "volunteers," but also "borrowing" wayward trucks in order to scrounge supplies from the train depot in Barstow. Soon his trucks were also filled with disparate Marines ready and willing to fight in Korea-wherever the hell that was.

At Pendleton, Litzenberg had tacitly approved of Davis's unorthodox recruiting methods, and now, at the Chosin Reservoir, the colonel had a stack of "after action" reports detailing how Davis, not content with studying an ongoing battle from a battalion commander's standard position in the rear, invariably "stayed on the low ground" at the front of his column whenever his unit engaged in a gunfight. Litzenberg also had firsthand testimony regarding Davis's fearlessness during the rescue at Turkey Hill. He wondered if there would be anyone left on Fox Hill for Davis to rescue.

Davis listened intently as Litzenberg spoke about the chances of relieving Captain Barber and Fox. He told Davis he had not been able to make contact with Barber since earlier that morning, and he was certain the company would be attacked again tonight. He warned that Fox's chances were so slim that if Davis did make it to Toktong Pass via the backdoor route, he might very well be walking into an American graveyard. Litzenberg added that if he managed to reach Barber by radio, I just might have to tell him to bug out before you even get there."

Davis said nothing.

At 6:30 p.m., Captain Barber ordered his XO, Clark Wright, to form up another supply recovery detail while the 81-mm mortars and the howitzers at Hagaru-ri bombarded the Chinese. Wright's unarmed Marines ran full speed out into the valley carrying empty stretchers, filled them with ammunition, and returned without drawing fire.

The men were glad of the exercise-some had reached the point where being taken out by a sniper was preferable to hunching down in a foxhole waiting to slowly freeze to death-but Barber found the lack of enemy activity strange. He decided to press his luck and sent Wright and his men out for another run. Still no fire. Barber had no idea what it meant, but he was not a man to spit in fortune's eye. This was, however, enough for the night; the enemy could have whatever remaining scattered grenades they could find. His "effectives" might be hungry and cold but they would not lack weaponry and ammunition.

As a result of the airdrops and the captured weapons, each American foxhole now resembled an international gun show. At least that was Dick Bonelli's thought as he eyed the armaments lining the parapet of the hole near his light machine gun emplacement up on the east crest. Walt Klein and Frank Valtierra had covered the rim with two Thompson submachine guns, an 8-mm Mauser rifle, a forty-five-caliber American-made Grease Gun, a German-made machine pistol with a sack of ammo, and a 1903 Springfield rifle complete with stripper-clipped ammunition rounds. Their M 1 s were crisscrossed across a box of grenades.

"Startin' a war?" Bonelli yelled.

Klein hollered back, "You remember what the El-Tee told us."

Once, out on a recon patrol near Hagaru-ri, Klein and Lieutenant McCarthy had stumbled upon a field covered with mounds of human feces. Somewhere along the march the lieutenant had picked up an old Chinese-made Mauser rifle. He took Klein aside, pointed to the frozen feces, and explained that in his opinion they were up against a hell of a lot more Reds than Division allowed. Then, brandishing the Mauser, he advised Klein never to pass up an opportunity to add an extra gun to his gear.

Now Klein cupped his hands to his mouth and yelled to Bonelli, "You know, about how you can never have enough firepower?"

Bonelli had no idea what he was talking about.

DAY FOUR

NOVEMBER 30, 1950

5

At 2 a.m. on November 30 the moon was suddenly obliterated by storm clouds. The hill was cold and dark when the whining loudspeaker system again screeched across its folds and pleats. The sound this time emanated from somewhere west of the cut in the road, behind the pile of five large rocks near the southwest base. The voice was that of an American, or someone purported to be an American. He identified himself as Lieutenant Robert Messman, an artillery officer from the Eleventh Marines. Messman announced that he had been captured two days earlier by the CCF near the Chosin, and he asked Fox Company to lay down its weapons and surrender.

"Just walk off the hill," the voice repeated over and again. Unlike the Chinese officer's conversational tone the previous night, this American voice sounded like someone reading from a script. "If you give yourselves up you will be treated fairly, in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, given food, and taken to shelter."

The idea that one of their own had turned traitor was too much for Fox Company. But because of the large rock pile no one could get a shot at the son of a bitch. Even after the 81-mm mortar crew sent up an illumination round, the American captive-if he was indeed an American-remained hidden. Up on the west slope Fidel Gomez fired off a short burst from a captured Thompson in the general direction of the five rocks, but that was mostly for show. It was, however, a good show-Marines all over the hill stood and cheered. "Messman" was not heard from again.

Five minutes later about a dozen men closest to the road on the left flank of the Second Platoon, including Gray Davis and Luke Johnson, watched as a squad of Chinese soldiers crept down the MSR. They settled in behind the pile of five rocks and began moving through the brush toward the American line. Hours earlier the Marines had squirmed several yards back from their holes and camouflaged themselves beneath the captured white blankets. They were so well concealed they appeared to be nothing more than lumps on the snow-covered hill. Lying prone and still, they allowed the Chinese to reach their old foxholes before they opened up. They cut every man down.

Farther up the west slope Bob Kirchner and Kenny Benson had fallen in with some more Second Platoon Marines who had gathered the sleeping bags of the American dead, stuffed them with snow and pine boughs, and placed them out in front of their foxholes. Then, on Lieutenant Peterson's orders, five American corpses were dragged from the "dead pile" and arranged in a sitting position in a semicircle near the sleeping bags, as if keeping watch. Soon enough Kirchner, Benson, and their squad saw the silhouettes of another Chinese squad creeping out of the deep ravine that bisected the west valley.

The enemy divided into two units. One attacked the decoy sleeping bags, running them through with bayonets several times. The other slipped behind the sitting corpses. It took several moments for the Chinese to realize something was not right. They stood, whispered to each other in nervous voices, and fell on the dead men with knives and bayonets. When their weapons failed to penetrate the frozen corpses, they understood the ruse. They instinctively swiveled toward the American lines. The Marines opened up with their rifles and BARs.

Standing near the command post tent, a sergeant named Robicheau-a last-minute addition to John Henry's heavy weapons unit on loan to Fox-listened to the firing on the west slope. They were coming again. But for some reason, call it a hunch, instead of looking toward the saddle, Robicheau made his way down the hill until he reached the bottom of the stand of fir trees.

He unpacked his night-vision binoculars and scanned the level ground across the MSR. In front of the woods at the base of the south hill, about 250 yards away, he saw three infantry companies massing into attack formation. More than five hundred men jogged in place and pumped their arms and knees while their political commissars urged them into a frenzy for "Mother China." To Robicheau they resembled nothing so much as a high school band preparing for a halftime show.

Out in front, like majorettes, were the grenadiers and sappers, their sacks of potato mashers slung over their shoulders, their satchel charges in hand. Next came the riflemen, with bayonets fixed, shouldering their Mausers like a horn section. Finally came the drummers, their booming automatic weapons, mostly Thompson submachine guns and Russian burp guns, pointed and at the ready.

By the time Robicheau raced back up the hill to inform Captain Barber, the Chinese were already on the move. Their jogging in place turned into a brisk trot. They performed a right flank maneuver and lanced across the snow-covered field. Their five lines stretched about seventy-five yards, with ten paces between each two lines. Then the trot became a cattle stampede. By the time they reached the road, the full frontal attack extended from just east of the larger hut to the west end of the cut bank on the MSR. This night they blew no bugles or whistles, and they held their fire in the minute or so it took them to cross the level ground between the South Hill and Fox Hill.

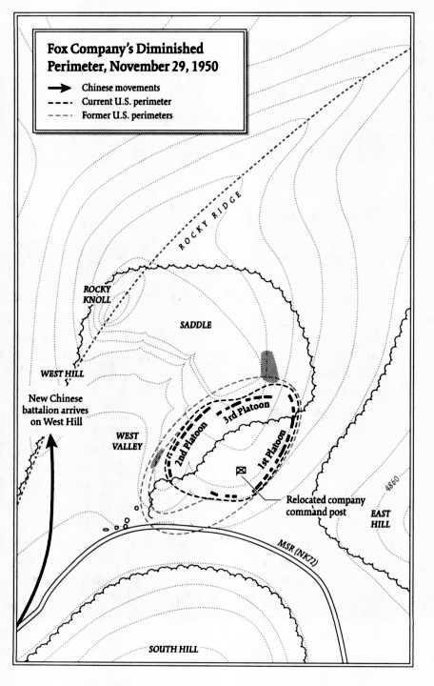

Barber watched them come. He assumed the advancing troops were the remnants of the five companies that had been torn up by howitzer shrapnel in the woods skirting the West Hill. He studied his defensive perimeter. From his vantage point looking down the hill, slightly to his left, were his heavy machine gunners and, to their left, the lowest foxholes of the First Platoon Marines, perhaps forty yards back from the road. To his right were the men from the Second Platoon who had ambushed the enemy squad from beneath their white blankets. They were now back in their holes and had again pulled their blankets over them. Though Peterson and his men were closer to the road by twenty yards than the men on the east slope, they were a bit more protected by the steep cut on the west end.