The King's Fifth (24 page)

Authors: Scott O'Dell

O

N THE SIXTH DAY,

having traveled some thirty leagues, as nearly as I could tell from the cross-staff, with no trace of horsemen in the country we had left, I made camp beside a stream and for a day rested the animals.

Traveling southward, we left the rolling country, thick grass, and numerous springs. On the tenth day we entered a plain that stretched away beyond the eye's reach.

We found no water here, used all that we carried, but two days later came to a brackish hole, where I watered the animals and refilled our casks. Both mules and horses needed rest, yet fearing that Roa followed us, I decided to press on and rode until late.

The morning of the fifteenth day we reached a shallow stream of mud-colored water. Thinking to throw Roa off our trail, I led the

conducta

into the stream and traveled westward for more than a league, along its many windings, leaving no tracks. I then cut back to our southward course again.

After this I lost some of my fear of being overtaken. Still, at night I never slept well and in the morning I woke uneasy.

We came upon the Inferno without warning.

At the crest of a steep rise, I saw beyond me a sink, a vast hole in the earth. It lay directly in our path, a distance of a league or more, extending east and west beyond my vision. It was a great depression in the earth, flat, naked of trees or brush, and stark white in color.

The way into it was gentle, except that the slope here was many-coloredâyellow, ochre, all shades of red, and even purple. In the far distance stood a high sierra covered with snow.

"The sierra," Father Francisco said, "is like the one you see from Toledo."

He had grown weary, walking beside the

conducta.

"That one you will see again," I said to cheer him. "And when you are there once more, you will have no need to go through the streets and alleys asking for

maravedis.

"

"It is not

maravedis

I will ask for," Father Francisco said. "It is for kindness and love."

I ignored his "kindness and love." "There is gold for both of us," I said.

"My share is yours," Father Francisco answered.

"There is gold also for gifts to the

Capilla de Santiago.

And for those of

Reyes Nuevos

and

San Ildefonso.

"

Father Francisco was silent.

It was a windy morning and cool, but as we traveled downward the wind ceased and the sun grew hot. When we reached the bottom the air was dead and the sun even hotter than during the days in Cortés' Sea.

There seemed to be an opening to the southwest, so I set out in this direction. The earth was drifted over with a white, dustlike powder, bitter to the taste, and

soft underfoot. Because of the softness and the heat we made poor progress, less than four leagues from early morning until dusk, three leagues of it before we reached the Inferno.

That night I gave the animals half-rations of water and some feed from the bags, but we drank little ourselves, though our throats we dry.

We broke camp before dawn. I felt certain that by traveling hard until an hour after the sun came up we would leave the Inferno and be in open country.

The sun struck us midway to our goalâthe sun beating down upon us and the burning, soft-white earth underfoot and the air so hot that it seared the lungs to breathe.

The animals began to stumble. Father Francisco, who insisted upon walking as he had on the whole journey, became partly blinded by the white, bitter dust so that he had trouble keeping up. Sighting a ledge of rocks which jutted into the sink, I led the way there, and in a thin strip of shade tethered the animals.

The shade lasted until past noon. Then we dug a pit in the soft earth and climbed in, resting there until the sun went down.

Father Francisco said, "This is the place to bury the gold. We cannot go farther with the burden."

"The burden is not one you carry," I replied. "You only need to carry yourself."

"The gold is evil," he said.

I gave the animals the rest of the water, save a little which we did not drink, and led the

conducta

out from

the ledge. A waning moon cast light on the white dust. By it, moving slowly, we made another league and halted.

In an hour we moved off again, traveling until sunrise, when we passed a row of sand dunes. To their far edge, shaded from the terrible sun, I led the

conducta.

The Inferno ended about a league to the south in a grove of willows, which meant the presence of water. But we could not hope to reach the grove until after sunset, for at least two hours after nightfall.

Gazing off to the northeast, to the ridge from which we had entered the sink, I saw a flash of light. I made out a group of small objects clustered there. The flash, I was sure, came from the sun striking a breastplate. The objects were Roa, his mules and the muleteers.

Roa's mules were fresh and lightly burdened. By the next morning he would overtake us. Yet I could not move until the cool of night.

At noon the sun bore down upon us. There was no shade. A light wind sprang up, which shifted the sand around. At the edge of a dune, we again dug a hole and crawled into it. I wondered if ever we would have the strength to crawl out.

Father Francisco lay a long time without speaking. Then he said, "Here, at last, we must bury the gold."

He spoke so softly that I scarce could catch his words. I pretended that I did not hear them.

When the sun cast shade I moved the animals, staying with them because they were restless, and because I could not drive a picket into the sand and make it hold.

From time to time, through waves of heat and blowing

sand, I caught the flash of a breastplate as Roa and his band dropped down from the ridge. Far off the sun shone on the snow fields. I watched it sink, then went to rouse Father Francisco.

The hole was empty. On the bottom lay the cask, with what water there remainedâa few mouthfuls. I took up the cask and shook it. The few mouthfuls were still there. Propped against the side of the pit, beside his breviary, I saw Father Francisco's book of pressed flowers.

I crawled from the pit and called his name. The wind had increased. Sand was moving everywhere, but I made out three steps towards the dunes. I followed where they led and found him lying on his back, his arms outstretched.

He breathed as I picked him up, but by the time I had staggered back to the hole and lifted the cask to his lips, he was dead.

I waited until nightfall. I had little strength left, but with it I lifted Father Francisco's body and placed it across the saddle. He was as light as a boy. With empty cask and his book of flowers, I climbed up behind him.

At midnight I reached the willows. Long before, the mules had begun to prick up their ears, so I was not surprised to find a good spring there. I laid Father Francisco on the ground. I watered the animals, drank my fill, then tethered them in tall grass, and being too weak to unload the packs, lay down and slept.

The sun awakened me. Frightened, I jumped to my feet and glanced toward the Inferno that lay behind. The white, bitter dust glittered. There was no sign of Roa.

I dug a grave in the grass beside the spring and buried Father Francisco, placing his ivory cross upon his breast. Then I walked to where the animals were tethered and looked at the bags of gold, which I had not been able to unload. As I stood there, I heard the little priest speak again, saying, "Where do we go with this evil burden?"

"Where, indeed?" I asked myself.

"The gold is evil," I heard him say. "Here, at last, we must bury it."

"It is evil," I answered. "It is the cause of your death and the guilt for your death is mine."

The sun was very hot and I went back to the spring. I sat down in the grass and closed my ears against the voice that was speaking to me. Across the stream, in their wooden saddles, were the bags of gold. I counted them and changed the gold into golden coins, but the numbers got confused in my head because the voice kept speaking. Then I realized that the voice was no longer Father Francisco's. It was my own that I heard and the words came from deep within me.

I looked back at the path the train had made in the white dust. Sand was blowing and the horizon wavered before my eyes, yet I noticed no more than a furlong away, on the very edge of the Inferno, rows of yellow craters, which I had passed in the night and not seen.

Crossing a stretch of white dust, I made my way among them. There were fifty or more, all much alike, most of them a long jump across and filled with poisonous-looking water. The green bubbles, which rose from them, gave off a sulphurous stench.

I went back, mounted my horse, and led the

conducta

out. Picking the largest of the craters, I took the nugget I had found at Nexpan and tossed it into the yellow water. I then untied the saddles and one by one I began to drop the bags into the water. They sank fast and for a long time, since the crater was deep, bubbles rose to the surface. Each bag that I dropped into the crater was like a heavy stone, which I had carried on my back and was now Tree of.

I led the train back to the spring and tethered the mules and all the horses save two, for Roa. I filled the cask with water, strapped Father Francisco's book to the saddle, and rode south. I rode hard all morning, until the gold and the Inferno were far behind me.

The third day I came to a wide river. Currents were strong where I stood, so I moved east for a league or more. There at a good place to cross I saw a tall tree, the only one I had passed on the journey.

Across its broad trunk, carved deep, was a message. The message read:

ALARCÃN CAME THIS FAR. THERE ARE LETTERS UNDER THE TREE.

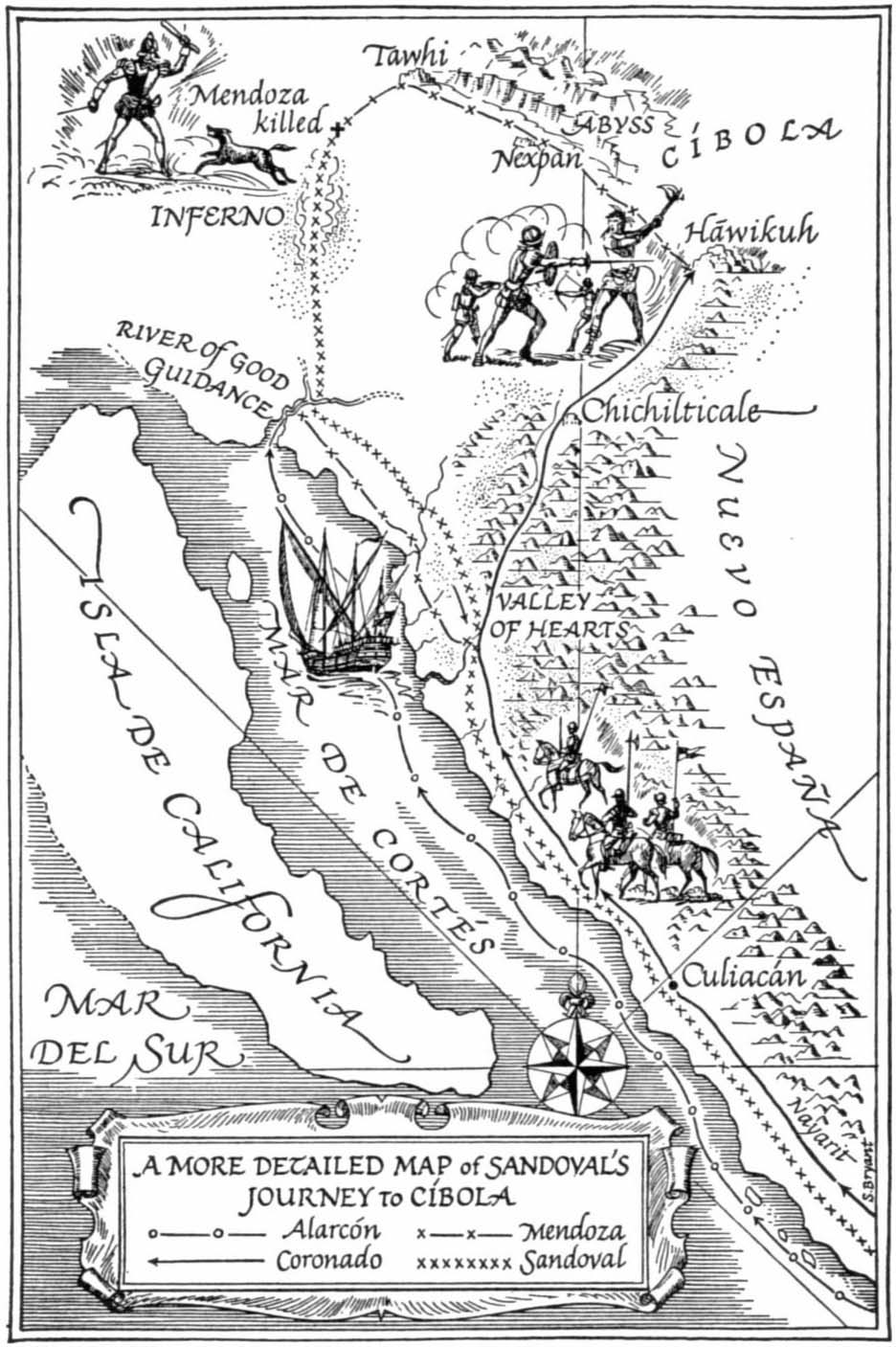

I found no letters, though I searched, digging in a wide circle around the tree. But the message carved on its trunk I read many times before I left. I remembered it as I crossed the river and rode south to the Valley of Hearts and Culiacan. I remembered it when I told my story in that city and was put under arrest. And I remember it now as I write of it in the Fortress of San Juan de Ulúa.

The Fortress of San Juan de Ulú

a Vera Cruz, in New Spain

The thirteenth day of October

The year of our Lord's birth, 1541

I

AWAKEN EARLY,

though I have written most of the night. The sky is overcast and a wind blows from the north. It has the feel of winter.

Don Felipe's Indian brings my breakfast, a large platter of

chorizos

and a mug of chocolate. I eat little but drink the chocolate, which is hot and frothy.

At mid-morning Don Felipe himself appears. He closes the iron door and stands against it, his cudgel chin thrust out. He seems to be worried about something.

"

Hidalgo,

" he says, very cheerful, which is always a bad sign with him, "you must have slept well, for you look as fresh-cheeked as a rose in the Queen's garden. Ah, to be young once more. When every day is a sweet confection to be popped into the mouth..."

I wait, half-listening to this poetic outburst, until he is finished, then I ask about the verdict of the Audiencia.

"We will have word from it this afternoon," he says, "if all goes well with the judges, who are old and given to delay."

"Have you heard any news about the verdict?"

"None, but I do have news about another matter." He

takes a step towards me and lowers his voice. "Word has come to me that the royal fiscal and some of his cohorts are sending an expedition to CÃbola. They will use the notes you have given to the Audiencia. Tell me,

caballero,

will these notes lead them to the hiding place of the treasure?"

"The notes may lead there, but the treasure cannot be found."

"The map you make for me," Don Felipe says, "when will it be completed?"

"By tomorrow," I answer, "but I warn you, the gold will not be found."

"What do you mean?"

"I mean that it lies at the bottom of a deep crater. A hole, a spring if it can be called that, of burning water."