The King's Fifth

Authors: Scott O'Dell

Scott O'Dell

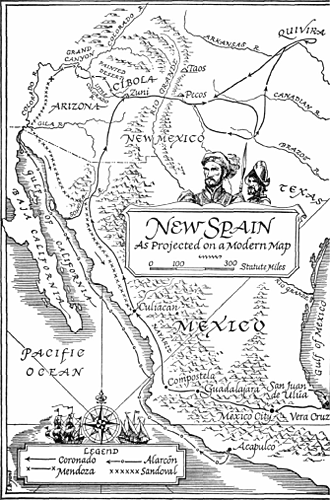

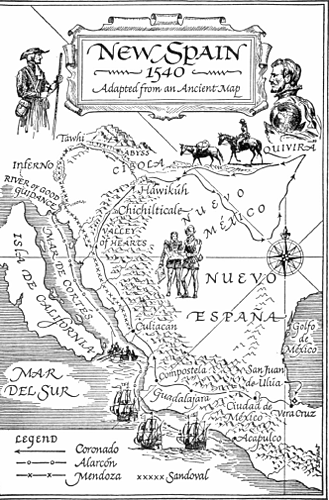

Decorations and Maps by Samuel Bryant

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON

Copyright © 1966 by Scott O'Dell

Copyright © renewed 1994 by Elizabeth Hall

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park Avenue

South, New York. New York 10003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER AC

66-10726

ISBN:

0-395-06963-7

ISBN

-13: 978-0-395-06963-9

PRINTED IN THE U.S.A.

VBÂ 25 26 27 28 29 30

For LUCE

The Fortress of San Juan de Ulúa

Vera Cruz, in New Spain

The twenty-third day of September

The year of our Lord's birth, 1541

I

T IS DARK NIGHT

on the sea but dusk within my cell. The jailer has gone. He has left six fat candles and a bowl of garbanzos that swim in yellow oil.

I am a fortunate young man. At least this is what the jailer said just before he closed the iron door and left me alone.

He stands in the doorway and says under his breath, "Garbanzos, a slice of mutton, the best oil from Ãbeda! Who ever has heard of such fine fare in His Majesty's prison? And do not forget the candles stolen from the chapel, for which I could be tossed into prison myself. Worse, mayhap."

He pauses to draw a long finger across his throat.

"Remember these favors," he says, "when you return to the land of the Seven Cities. Remember them also if by chance you do not return. Remember, Estéban de Sandoval, that I risk my life in your behalf!"

He leans toward me. His shadow fills the cell.

"I have

maravedis,

a few cents," I answer, "to pay for your kindness."

"Kindness!" He grinds the word between his teeth.

During his life he must have ground many words for his teeth are worn close. "I do not risk my neck from kindness, which is a luxury of the rich. Or for a few ducats, either. Let us be clear about this matter."

He closes the iron door and takes one long step toward me.

"I have seen the charge brought against you by the Royal Audiencia," he says. "Furthermore, I deem you guilty of that charge. But guilty or not, I ask a share of the gold you have hidden in CÃbola. The King demands his fifth. A fifth I likewise demand. For I do more than he and at dire peril to my life."

His words take me aback. "If I am found guilty," I say evasively, "then I shall never return to CÃbola."

"It is not necessary that you return. You are a maker of maps. A good one, it is said. Therefore you will draw me a map, truthful in all details, by which I can find my way to this secret place." His voice falls to a whisper. "How much gold is hidden there? Tell me, is it enough to fill the hold of a large galleon?"

"I do not know," I answer, being truthful and at the same time untruthful.

"Enough, perhaps, to fill a small galleon?"

I am silent. Two fingers thrust toward me, sudden as a snake, and nip my arm.

"You may have heard the name QuentÃn de Cardoza," the jailer says, "An excellent gentleman, in any event, and innocent as a new-born babe. Yet four years he spent in San Juan de Ulúa, in this very cell. And died in this cell before his trial came to an end. You also may spend four

years here, or five, or even more. Trials of the Royal Audiencia consume time, as dropping water consumes stone. These trials have two equal parts. One part takes place in the chambers above, before the judges. The other part takes place here below, under my watchful eye."

He tightens his grip on my arm and moves his face so close to mine that I can see the bristles on his chin.

"Remember,

señor,

that what I do for you I do not for a handful of

maravedis.

Neither for money nor from kindness. I do it only because of a chart, limned with patience and skill, which you will make for me."

"It is a crime," I answer, still being evasive, "to draw a map without permission of the Council of the Indies."

He loosens his grip upon my arm. "The Council," he says, "resides in Spain, thousands of leagues away."

"So also does the King who accuses me of theft," I boldly say.

"Yes, but do not forget that the King's loyal servant, Don Felipe de Soto y RÃos, does not reside in Spain. He stands here before you, a man with one eye which never sleeps."

Don Felipe steps back and squares his shoulders. He is tall, with a long, thin forehead and a jaw like a cudgel. He says nothing more. Softly, too softly, he closes the door and slides the iron bolt. His footsteps fade away into the depths of the fortress.

Don Felipe de Soto y RÃos! The name stirs in my memory. Is he the one who years ago marched with bloody Guzmán, who slaughtered hundreds of Tarascans and

dragged their king through the village streets tied to the tail of a horse?

I cannot say for certain. It does not matter. Whoever he is he has done much for me during my six days in San Juan de Ulúa. My cell is the largest in the prison, three strides one way, four strides the other. He has given me the bench I write upon, candles, paper, an inkbowl and two sharp quills.

I know now why he has given me these things. Still, I have them. In return, because I must, I shall draw him a map of CÃbola, proper in scale, deserts and mountains and rivers set down, also windroses and a Lullian nocturnal. As for the treasure which he covets, who knows where it lies? Even I who secreted it, do I know? Could I ever find it again?

Don Felipe I will not see until dawn. I can give my thoughts to the trial that begins in two days, curiously enough on my seventeenth birthday. I will put down everything as I remember it. And write carefully from the beginning, each night while the trial lasts.

Yes, I shall put down everything, just as I remember it.

I am a maker of maps and not a scrivener, yet I shall do my best. By this means, I may find the answer to all that puzzles me. God willing, I shall find my way through the labyrinth which leads to the lair of the minotaur. This should help me in the trial I face before the Royal Audiencia, for if I do not clearly know what I did or why it was done, how can I ask others to know?

I am now ready to begin. The night stretches before me. It is quiet in my cell except for the sound of water

dripping somewhere and the lap of waves against the fortress walls. The candle sheds a good light. Some say that in the darkness one candle can shine like the sun.

And yet where is the beginning? What first step shall I take into the maze of the minotaur?

Should I begin on that windy April day, on the morning when the eagles rose out of the darkness below the mighty cliffs of Ronda? When I said goodbye to my father and with my few needments under my arm climbed into the stagecoach that was to take me to Seville? But this is two years in the past and the boy I was is dim in my memory. I have even forgotten my father's shouted advice as the coach moved out of the cobbled square. That it was good advice, I am certain. Also certain is the fact that I did not heed it.

Perhaps I should begin on the day I received my diploma in cartography from the Casa de Contratación and within the hour sailed from Seville for the New World. But this too is dim in my memory, hidden beneath the fateful things that since have befallen me. As is the voyage to Vera Cruz in New Spain and the long journey to the mountain stronghold of the dead king, Montezuma.

Should I start with the day and the circumstances of my meeting with Admiral Alarcón, the oath I took to bear him fealty and of the night our fleet sailed north from Acapulco?

But what of Zia? Do not these writings truly begin with her, the Nayarit girl of the silver bells and the silvery laughter, who guided the

conducta

of Captain Mendoza into the Land of CÃbola?

No, 1 see now that the story really begins when Admiral Alarcón sailed into Cortés' Sea. It begins on the morning when Captain Mendoza first thought to seize command of the galleon

San Pedro.

Yes, this day is the beginning.

Through the small, barred window I can see a star. The candle sheds its good light. Now as I write of Captain Mendoza's plans to raise a mutiny and what happened to them and of the events that led me to Chichilticale, may God enlighten my mind and guide my pen!

I

T WAS EIGHT BELLS

of the morning watch, early in the month of June, that we entered the Sea of Cortés. On our port bow was the Island of California. To the east lay the coast of New Spain.

I sat in my cabin setting down in ink a large island sighted at dawn, which did not show on the master chart. The day was already stifling hot, so I had left the door ajar. Suddenly the door closed and I turned to face Captain Mendoza.

He glanced at the chart spread out on the table. "Is this Admiral Ulloa's?" he asked.

"A copy," I said, "which I am making as we move north."

"A true copy?"

"True, sir."

He leaned over my shoulder. "Where are we, Señor Cartographer, at the present hour?"

"This was our position yesterday at sunset." I put my finger on the chart. "We have made some twelve leagues since."

Mendoza stared down at the country that lay east and north of the spot where my finger rested. It was a vast blank space, loosely sketched. Upon it no mark showed, no river, no mountain range, no village, no cityâonly the single word

UNKNOWN

.

He turned and went to the door. I thought that he was leaving, having learned what he wished to know, but he stood there for a time and stared out at the calm sea, the white surf, the hills that rolled away to the east. Then he closed the door and leaned against it, looking down at me.

"You work hard," he said. "Your lantern burns late. I seldom encounter you."

"There is much work," I answered.

"A little sun would help. A few hours on deck. You are pale. A boy your age should move around. Not sit over a chart all day and half the night. How old are you? Seventeen? Eighteen?"

"Fifteen, sir."

"I presume from the city of Salamanca. The country of scholars, where everyone is pale, red around the eyes from reading, and has ink-stained fingers."

"No, from Ronda."

"Truly? This is difficult to believe. Those from Ronda are usually venturesome fellows. Stout with the sword. Good horsemen. Restless, ready for anything."

I looked down at the chart and the island I had not yet finished.

"Ulloa shows nothing for all of this?" he said, passing his hand across the blank space.

"Nothing," I answered. "He skirted the coast as far

north as the River of Good Guidance, which he discovered, but did not venture inland."

"What of Marcos de Niza and Stephen, the Moor, the ones who have seen the Seven Cities of Gold?"

"The Moor was killed at Háwikuh and his bones lie there. Father Marcos is an explorer, not a maker of maps. Neither one left a record of CÃbola nor how it was reached."

"Then the chart is of no value for those who might travel there?"