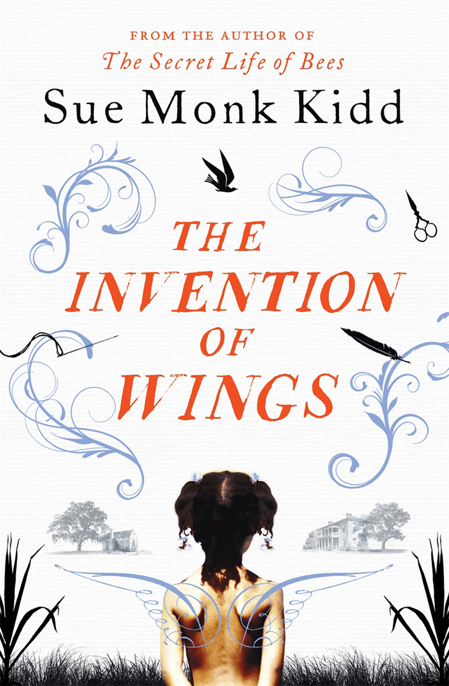

The Invention of Wings

Read The Invention of Wings Online

Authors: Sue Monk Kidd

Copyright © 2014 Sue Monk Kidd Ltd.

The right of Sue Monk Kidd to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC,

A Penguin Random House Company

Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publication may only be reproduced, stored, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with prior permission in writing of the publishers or, in the case of reprographic production, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency.

First published in Great Britain as an Ebook by Headline Publishing Group in 2014

All characters – other than the obvious historical figures – in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978 1 4722 1276 4

Cover design: cabinlondon.co.uk

Cover images © Martin Barraud/Getty Images (child) and Michael Eudenbach/Getty Images (trees); Library of Congress (Charleston Houses); Big Joker/Alamy (needle and thread)

Author photograph © Roland Scarpa

HEADLINE PUBLISHING GROUP

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London

NW1 3BH

Table of Contents

Part One: November 1803–February 1805

Part Two: February 1811–December 1812

Part Three: October 1818–November 1820

Part Four: September 1821–July 1822

Part Five: November 1826–November 1829

From the celebrated author of the international bestseller

The Secret Life of Bees

comes an extraordinary novel about two exceptional women.

Sarah Grimké is the middle daughter. The one her mother calls difficult and her father calls remarkable. On Sarah’s eleventh birthday, Hetty ‘Handful’ Grimké is taken from the slave quarters she shares with her mother, wrapped in lavender ribbons, and presented to Sarah as a gift. Sarah knows what she does next will unleash a world of trouble. She also knows that she cannot accept. And so, indeed, the trouble begins …

A powerful, sweeping novel, inspired by real events, and set in the American Deep South in the nineteenth century, THE INVENTION OF WINGS evokes a world of shocking contrasts, of beauty and ugliness, of righteous people living daily with cruelty they fail to recognise; and celebrates the power of friendship and sisterhood against all the odds.

Sue Monk Kidd’s debut novel, THE SECRET LIFE OF BEES, spent more than 100 weeks on the

New York Times

bestseller list, has sold more than eight million copies worldwide, was long-listed for the Orange Prize and has been translated into thirty-six languages. It was also turned into an award-winning major motion picture starring Dakota Fanning, Jennifer Hudson and Alicia Keys.

Her second novel, THE MERMAID CHAIR, was a number one

New York Times

bestseller. She is also the author of several widely acclaimed non-fiction titles including THE DANCE OF THE DISSIDENT DAUGHTER, WHERE THE HEART WAITS and, with her daughter Ann Kidd Taylor, TRAVELLING WITH POMEGRANATES.

Sue Monk Kidd lives with her husband Sandy in Florida.

Novels

The Secret Life of Bees

The Mermaid Chair

The Invention of Wings

Non-fiction

When the Heart Waits

The Dance of the Dissident Daughter

Firstlight

Travelling with Pomegranates (with Ann Kidd Taylor)

‘Wonderful … by turns funny, sad, full of incident and shot through with grown-up magic reminiscent of Joanne Harris’

Daily Telegraph

‘Wonderfully written, powerful, poignant and humorous … Do read it’ Joanna Trollope

‘Intoxicating … The tale of one motherless daughter’s discovery of what family really means … and of the strange and wondrous places we find love’

Washington Post

‘A narrative as skilful and sweet as a honeycomb. Uplifting and warm-hearted … moving’

Literary Review

‘A truly original Southern voice’ Anita Shreve

‘Charming, funny, moving’ Elizabeth Buchan,

The Times

To Sandy Kidd

with all my love

November 1803–February 1805

Hetty Handful Grimké

T

here was a time in Africa the people could fly. Mauma told me this one night when I was ten years old. She said, “Handful, your granny-mauma saw it for herself. She say they flew over trees and clouds. She say they flew like blackbirds. When we came here, we left that magic behind.”

My mauma was shrewd. She didn’t get any reading and writing like me. Everything she knew came from living on the scarce side of mercy. She looked at my face, how it flowed with sorrow and doubt, and she said, “You don’t believe me? Where you think these shoulder blades of yours come from, girl?”

Those skinny bones stuck out from my back like nubs. She patted them and said, “This all what left of your wings. They nothing but these flat bones now, but one day you gon get ’em back.”

I was shrewd like mauma. Even at ten I knew this story about people flying was pure malarkey. We weren’t some special people who lost our magic. We were slave people, and we weren’t going anywhere. It was later I saw what she meant. We could fly all right, but it wasn’t any magic to it.

The day life turned into nothing this world could fix, I was in the work yard boiling slave bedding, stoking fire under the wash pot, my eyes burning from specks of lye soap catching on the wind. The morning was a cold one—the sun looked like a little white button stitched tight to the sky. For summers we wore homespun cotton dresses over our drawers, but when the Charleston winter showed up like some lazy girl in November or January, we got into our sacks—these thickset coats made of heavy yarns. Just an old sack with sleeves. Mine was a cast-off and trailed to my ankles. I couldn’t say how many unwashed bodies had worn it before me, but they had all kindly left their scents on it.

Already that morning missus had taken her cane stick to me once cross my backside for falling asleep during her devotions. Every day, all us slaves, everyone but Rosetta, who was old and demented, jammed in the dining room before breakfast to fight off sleep while missus taught us short Bible verses like “Jesus wept” and prayed out loud about God’s favorite subject,

obedience.

If you nodded off, you got whacked right in the middle of God said this and God said that.

I was full of sass to Aunt-Sister about the whole miserable business. I’d say, “Let this cup pass from me,” spouting one of missus’ verses. I’d say, “Jesus wept cause he’s trapped in there with missus, like us.”

Aunt-Sister was the cook—she’d been with missus since missus was a girl—and next to Tomfry, the butler, she ran the whole show. She was the only one who could tell missus what to do without getting smacked by the cane. Mauma said watch your tongue, but I never did. Aunt-Sister popped me backward three times a day.

I was a handful. That’s not how I got my name, though. Handful was my basket name. The master and missus, they did all the proper naming, but a mauma would look on her baby laid in its basket and a name would come to her, something about what her baby looked like, what day of the week it was, what the weather was doing, or just how the world seemed on that day. My mauma’s basket name was Summer, but her proper name was Charlotte. She had a brother whose basket name was Hardtime. People think I make that up, but it’s true as it can be.

If you got a basket name, you at least had something from your mauma. Master Grimké named me Hetty, but mauma looked on me the day I came into the world, how I was born too soon, and she called me Handful.

That day while I helped out Aunt-Sister in the yard, mauma was in the house, working on a gold sateen dress for missus with a bustle on the back, what’s called a Watteau gown. She was the best seamstress in Charleston and worked her fingers stiff with the needle. You never saw such finery as my mauma could whip up, and she didn’t use a stamping pattern. She hated a book pattern. She picked out the silks and velvets her own self at the market and made everything the Grimkés had—window curtains, quilted petticoats, looped panniers, buckskin pants, and these done-up jockey outfits for Race Week.

I can tell you this much—white people lived for Race Week. They had one picnic, promenade, and fancy going-on after another. Mrs. King’s party was always on Tuesday. The Jockey Club dinner on Wednesday. The big fuss came Saturday with the St. Cecilia ball when they strutted out in their best dresses. Aunt-Sister said Charleston had a case of the grandeurs. Up till I was eight or so, I thought the grandeurs was a shitting sickness.

Missus was a short, thick-waist woman with what looked like little balls of dough under her eyes. She refused to hire out mauma to the other ladies. They begged her, and mauma begged her too, cause she would’ve kept a portion of those wages for herself—but missus said, I can’t have you make anything for them better than you make for us. In the evenings, mauma tore strips for her quilts, while I held the tallow candle with one hand and stacked the strips in piles with the other, always by color, neat as a pin. She liked her colors bright, putting shades together nobody would think—purple and orange, pink and red. The shape she loved was a triangle. Always black. Mauma put black triangles on about every quilt she sewed.