The Indian Clerk (36 page)

Authors: David Leavitt

Alice turned. Standing before her, radiant and very pregnant, was Mrs. Chase. Littlewood's friend, whom she and Gertrude had

met, albeit briefly, at the zoo.

"We know each other," Alice said.

Mrs. Chase's face buckled with confusion. "I'm sorry, do we?" she asked. "My memory's terrible these days. It's curious, this

is the third time I've been pregnant, and each time something very odd happens. Last time I was constantly thirsty."

"It's all right," Alice said. "I'm Alice Neville. We met at the zoo—oh, it feels like years ago. I was with Gertrude Hardy."

Memory, then, a reawakening that was visible in Mrs. Chase's eyes. But a good memory?

"Of course," she said, smiling. "How lovely to see you."

And she reached out her hand, and took Alice's arm, and mysteriously, thrillingly, kissed her on the cheek.

New Lecture Hall, Harvard University

B

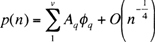

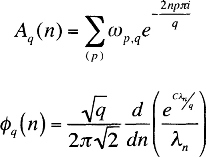

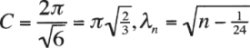

Y THE END of 1916, we had the partitions formula. Here is what it looked like:

where

the sum being over

p'

s that are positive integers less than and prime to

q,v

is of the order of √n and

w

p,q

is a certain 24q-th root of unity and

Today whenever I write out the formula, I think: what an extraordinary creature! It is like one of those circus bears trained

to balance a motor car on its nose, or some such thing. There is dazzle in its every baroque convolution; yet the dazzle belies

the laborious process by which we got to it: a process, sometimes, of trial and error, as if we were standing in a room the

walls of which were lined with thousands upon thousands of light switches, and we had to try each one with the goal of eventually

arriving at a very particular degree of brightness. One switch would bring us close—and then we would try another and the

light would be blinding, or the room would go dark. Still, over weeks, we got closer, and then, almost without noticing, one

day we had the light almost right.

Now I must address, once again, the mystic faction that accepts, without a hint of incredulity, Ramanujan's claim that his

mathematics came to him in dreams, or that formulae were inscribed upon his tongue by a deity. I am sure that he believed

this to be the case, just as I am sure that, on occasion, he did haul up from the depths of his imagination treasure chests

from which glittering jewels gleamed forth, while the rest of us were chiseling away in the diamond mines with our pickaxes.

And yet, the ability to voyage on a regular basis (as poor Moore could not) into regions of the mind from which most of us

are barred does not necessarily require the intervention of a goddess. On the contrary, all of us experience, on occasion,

such "miracles."

Let me give an example. All of you who know him would agree that no mathematician is less "mystic" than Littlewood. Yet even

Littlewood described to me once an occasion on which, while working on the

M

1

< (1 —

c

)

M

2

problem for real trigonometrical polynomials, his "pencil wrote down" a random formula that turned out to be the key to the

proof. According to Littlewood, this episode was "almost unattended by consciousness"—a claim which, had psychoanalysis been

in vogue during the war, would have been of considerable interest to its adherents. In those years it would have been of interest

only to adherents of the Ouija board. And that is just my point. Were I to announce, today, that a goddess was writing formulae

on

my

tongue, you would show me the way to the asylum. But Ramanujan was Indian, and so he was labeled a "visionary." Yet what this

label neglects is the price he paid for his vision, and how hard he had to work to attain it.

While it is true, for instance, that the formula sprang from one of the conjectures that he had brought with him from India,

it must be borne in mind that the journey from that initial conjecture to the final product was laborious and long. It was

a process of refinement, and while it is fair to say that, had I not brought to the table certain technical know-how that

I possessed and that he did not, we couldn't have got there, let me emphasize that my contribution was not

merely

technical. I contributed my own share of vision.

I remember it was Christmas when we finished. I was at Cranleigh, at the house in which I had grown up, the house my mother

shared with my sister, and to which I returned on holidays. My mother, at this point, had been dying for several years. Every

few months, it seemed, she would come close to death, she would see the angels beckoning her, and then, at the eleventh hour,

something would pull her back from the brink, and before we knew it she would be out of bed, making tea and proposing a game

of Vint. To this game—does anyone now remember it?—she was devoted. It was Russian in origin, a variant on Contract Bridge.

(I'm told "Vint" means "screw" in Russian.) That Christmas we played it for hours every day, with our neighbor and Mother's

friend, Mrs. Chern, making up the fourth. Mrs. Chern cheated, I think. I wonder if Mother noticed.

I may have already mentioned that she possessed a certain degree of mathematical talent—a talent, I am sorry to say, that

in her later years she applied exclusively to the playing of Vint, which at least has the advantage of being a harmless pastime,

in contrast to the occult evils in which Ramanujan's mother indulged. And Mother, to her credit, was a very good Vint player.

Almost as good as I was. That year I had the idea to write a book on how to win at Vint, and make enough money from it that

I could give up teaching. My goal, I told Russell, was to score a million points, so that later, when people asked me what

I'd done in the Great War, I could say that I'd become head of the Vint League and given the world at large the benefit of

my expertise. But I never wrote the book, just as I never wrote the murder mystery about the Riemann hypothesis, and now,

when people ask me what I did during the Great War, I tell them, "I took care of Ramanujan." Perhaps, in my dotage, I shall

write both.

But I am straying. To get back to partitions: that Christmas, Ramanujan sent me a postcard from Trinity, providing the last

piece in the puzzle and asking me to write up the final proofs. By then MacMahon, who was really the dearest of creatures,

had provided him with the typewritten copy of values he had come up with for p(n) up to n = 200, and Ramanujan had made his

comparisons. The formula was not precise. Instead it gave an answer that was correct only when rounded to the nearest integer.

Yet the difference was extraordinarily small. In the case of n = 100, for instance, our formula gave a value for p(n) of 190569291.996,

whereas the actual value was 190569292. A difference, to be precise, of .004.

Ramanujan was thrilled with the results. He called them "remarkable," which was unusually expressive, coming from him. It

was exciting enough news that I mentioned it to Mother, to whom I rarely spoke about my work, but as the question had no bearing

on Vint, she responded only with an air of contrived vagueness, saying something along the lines of "How nice" before drifting

back to the card table.

You see, she was really sharp as a tack. Vagueness was a convenience for her, to which she resorted when a subject bored her.

Her illness let her get away with all sorts of things she could never have got away with had she been well. And in the meantime

my poor sister danced attendance on her, indulging her every fancy and never managing to distinguish between the real complaints

and those that were purely fictitious. Poor Gertrude. In this regard she was far more credulous than I was.

Was the Russell business in full swing then? I think so. But no: most of the action—his arrest, the court case, his dismissal

from Trinity—must have happened in the late summer and early autumn, because I remember light coming over my shoulder as I

read one of his letters while drinking tea; at Christmas it would have been dark already at teatime, a darkness which the

wartime prohibition on streetlights only deepened. The habit of memory (my memory, at least) is to organize by category, not

date. It's as if some immemorial secretary has plucked events out of their natural sequence and then filed them away under

such headings as "Ramanujan," "The War," "The Russell Affair," so that now, in order to see clearly the chronology, I have

first to dig out from each file the pertinent details of a moment and then place them alongside the details of another moment,

dug out of another file. Nor, once I've completed this elaborate reconstruction, am I quite convinced of its veracity.

By the way, this is an episode of which, if you Harvard men have heard of it at all, you have probably heard only because

it touches lightly on the history of your own illustrious university. For in 1916 not only was Russell dismissed by Trinity,

he was refused a passport by the Foreign Office, and this meant that he could not take up a position he had been offered at

Harvard. All of which suited his intentions perfectly.

I shall try to be as brief as possible. Russell was not, as is commonly believed, dismissed by Trinity

after

he was sent to prison. In fact, by the time he was sent to prison, two years had passed since his dismissal. This second arrest

resulted from an article he wrote for the

Tribunal

that was adjudged likely to muck up relations between England and the United States; my own personal belief is that he wrote

the article

in order

to be sent to prison, and thereby prove once and for all his willingness to endure sufferings, if not equal to, then at least

approaching those of the men at the front. For it was difficult, in his position, to escape being labeled a shirker, and prison

would show the manliness of his opposition.

But this is jumping ahead. In 1916 I don't believe prison was as yet on Russell's mind. What he had done was acknowledge, in

a letter to the

Times,

authorship of a leaflet issued by the No Conscription Fellowship. The leaflet contained language the government considered

inflammatory and possibly illegal, and so when Russell announced that he had written it, the Crown had no choice but to prosecute.

The exact charge was that in the leaflet Russell had made statements "likely to prejudice the recruiting and discipline of

His Majesty's forces." This was just what he wanted, for now he could use the trial as a soapbox for his pacifism. By getting

himself prosecuted and, if possible, convicted, he hoped both to draw attention to the injustices being suffered by the conscientious

objectors and to obtain a larger audience for his tirades.

The trouble was, his tirades could go over the heads of their intended audience. At the trial, he was in every way the logician,

dismantling the prosecution's case as if it were a piece of specious mathematical reasoning. For instance, in addressing the

principal charge against him—that the leaflet prejudiced recruiting—he noted that, at the time that the leaflet was issued,

single men were already subject to conscription, while married men were not. Therefore the only deleterious influence that

the leaflet might have would be on married men who were considering voluntary enlistment and were therefore,

ex hypothesis

(Russell actually used this phrase), not conscientious objectors. The leaflet, Russell summed up, merely informed such men

that, if they chose to "pose" as conscientious objectors, they would be liable to two years' hard labor. "I do not consider

that knowledge of this fact," he said, "is likely to induce such a man to pretend that he is a conscientious objector when

he is not": an argument that, while it might dazzle a Trinity undergraduate, was only likely to antagonize a Lord Mayor.

And antagonize the Lord Mayor it did. Indeed, I would say that the strategy backfired completely, with the result that Russell

was found guilty and fined £100, which he refused to pay. And the irony is, he could easily have got off. The Crown's case

against him was incredibly weak. Now I suspect that in fact his game was far more subtle than any of us guessed; that, having

recognized the weakness of the case, he had deliberately chosen to employ an approach that would annoy the Lord Mayor and

insure his conviction. Now, because he refused to pay the fine, all the goods in his rooms at Trinity would go on the auction

block. The newspapers would report the auction, and he would look every inch the martyr.