The Illusion of Conscious Will (28 page)

Read The Illusion of Conscious Will Online

Authors: Daniel M. Wegner

Tags: #General, #Psychology, #Cognitive Psychology, #Philosophy, #Will, #Free Will & Determinism, #Free Will and Determinism

Thoughts of Action

Unconscious action can also be understood in terms of what a person is thinking consciously and unconsciously at the time of action. It is possible that both kinds of representation of action might contribute to the causation of an action, and in either event we would say that real mental causation had taken place. Although the notion of the ideal conscious agent only allows for causation by conscious thoughts, we must consider as well the whole range of thoughts or mental states that might influence action without consciousness.

8.

Vallacher et al. (1998) explore the idea that action identifications vary over time.

9.

There is a whole lot more I could say about action identification, but since much of it has already been said, it seems silly to repeat it here. After all, this is only a footnote. The fuller story is in Vallacher and Wegner (1985). In essence, we tried to develop an operating system for a human agent based on the premise that people always have some idea of what they are doing.

What sorts of unconscious thoughts could cause action? Certainly, Freud’s notion of the unconscious mind tapped a broad definition of unconscious mental causation. His postaction interpretations often presumed whole complexes of unconscious mental material influencing the simplest action. A woman calling her husband by her father’s name, for example, could provide grist for a lengthy interpretive exercise invoking unconscious thoughts of her childhood, her sexuality, and all the usual psychoanalytic gremlins. This view of the unconscious is far too sweeping, allowing unconscious thoughts to be the length of novels. It is probably the case that the unconscious thoughts powering action are more rudimentary.

A contemporary version of the theory of unconscious mental causation was voiced by Jerome Bruner (1957) in terms of the idea of

readiness

. Unconscious thought can be understood as a kind of readiness to think of something consciously. Bruner suggested that some limited array of mental states guiding perception and action could be active yet not conscious. The unconscious readiness to think of food could make us notice it is time for lunch, just as a readiness to think of competition could make us punch the accelerator and speed past another driver. Such readiness has been described in terms of thoughts that are

accessible

at the time of action (Bargh and Chartrand 1999; Higgins and King 1981; Wegner and Smart 1997). An accessible thought is one that the person may or may not be able to report as conscious but that has some measurable influence on the person’s conscious thoughts or observable actions.

Thoughts can become accessible in several different ways. In some cases, thoughts are chronically accessible for a person (Bargh and Pratto 1986), as when a depressed person regularly tends to think about failure (Gotlib and McCann 1984; Wenzlaff and Bates 1998) or a person with a phobia finds thoughts of the phobic object always easy to bring to mind (Watts et al. 1986). At other times, a thought may be accessible as a consequence of the person’s contact with some cue in the environment. African American students who take a test that they are told is diagnostic of intellectual ability, for instance, show temporarily increased accessibility of thoughts about the racial stereotype of African Americans; in a word completion task, they become more likely to respond to the prompt “LA _ _” by filling in LAZY (Steele and Aronson 1995). People who try to concentrate on a thought can also increase its accessibility intentionally for a while, but paradoxically people who attempt not to think about a thought also will increase its accessibility briefly as well (Wegner and Erber 1992). However the thought is made accessible, though, the point is that it can then produce further thought or behavior even though it is technically unconscious.

Conscious thoughts are in mind and can be reported

now,

whereas accessible thoughts are not there yet and must be understood instead as having a potential to rise into consciousness. Distinguishing between conscious thought and accessible thought suggests that there are three ways in which a thought could be activated in mind prior to action (Wegner and Smart 1997). First, a thought might be conscious but not accessible. Such

surface activation

of the thought could occur, for example, when a person is trying to concentrate (without much luck) on studying for a test. Thoughts of the study materials might well be conscious, but thoughts of other things might be so accessible as to jump to mind at every turn and distract the person from the study topic. The thought of the test, then, would be conscious but not for long, because it was not simultaneously accessible.

A second way in which a thought could be present in mind prior to action would be if it were both conscious and accessible. Such

full activation

often happens for things we find deeply interesting or compelling, as when we are wallowing in some favorite thought of a splendid vacation, a fine restaurant, a great love, or a delicious revenge. Life’s greatest preoccupations often take the form of thoughts that are both in consciousness and also next in line to enter consciousness. We think of these things and, at the same time, have a high level of readiness to think of them some more. With full activation, moreover, we are seldom surprised with what our minds do, because with the thought already in consciousness, we know all along on what path the accessibility of this thought will continue to lead us.

The third form of cognitive activation suggested by this analysis concerns a thought that is accessible but not conscious. Such

deep activation

describes the nature of much of our mental life, but it is the mental life of the unconscious. Deep activation occurs, for example, when we have a conscious desire to have a thought—when we have a memory on the tip of the tongue, or are on the verge of a the solution to a problem we’ve not yet achieved. These thoughts are not yet in mind, but we are searching for them and they are thus likely to pop up at any moment. Deep activation also happens when we have a thought we have actively suppressed from consciousness.

When we try not to think about something, we may find we can indeed get away from it for a while. We achieve a kind of uneasy mental state in which, while the thought is not in consciousness, it is somehow very ready to jump back to mind. In these instances of deep activation, we may typically be surprised, and sometimes amazed or dismayed, when the accessible thought does have some influence. It may simply intrude into consciousness, popping into mind, or it may influence other things, such as our word choice, our focus of attention, our interpretation of events, or our observable action. These intrusions can sometimes alert us to the state of deep activation, but of course when they happen, the state no longer exists and is replaced by full activation. The thought is now conscious, and if it remains accessible, the characteristics of full activation have been met.

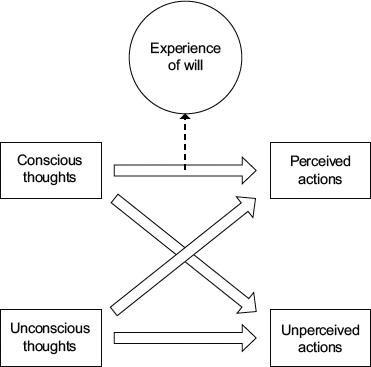

We can speak of thoughts influencing action from any of these states of activation—surface, deep, or full activation (Wegner and Smart 1997). The interesting point here is that a person will only know something about this causation if the thought is in surface or full activation (

fig. 5.2

), that is, when the thought is conscious. When deeply activated thoughts (accessible but not conscious) cause action, they can do so without the person’s experiencing any will at all. It is only when a thought is conscious prior to action that it can enter into the person’s interpretation of personal agency and so influence the person’s experience of will. When a thought is not conscious prior to action yet is accessible, it may influence action and leave the person with no clue about how the action came about. In this event, the person will normally experience a reduced sense of conscious will and perhaps begin looking elsewhere for the action’s causation. This is how we can explain the automatisms—cases when people do things influenced by nonconscious behavior priming (Bargh and Chartrand 1999; Dijksterhuis and van Knippenberg 1998).

Figure 5.2

The experience of conscious will occurs only when conscious thoughts are seen as causing perceived actions. If unconscious thoughts cause actions, will is not experienced; and if actions are unperceived, will is not experienced either.

The experience of will is not likely to occur when action is caused by unconscious thoughts.

The experience of will is also unlikely when the action itself goes unnoticed. When actions are subtle, when they involve only small changes or variations in movements already underway, or when they occur in the conindent of other actions or events that demand more attention, the actions may not be noticed enough to start an explanatory exercise. The process of assessing apparent mental causation, then, may never be undertaken. It is only in the special case when conscious thoughts precede easily perceived action that a causal attribution of action to thought may be made. People may invent false intentions after the fact of the action, then, when they have been led to perform an action by unconscious thoughts, or when they fail to notice the action until some later time and subsequently find they do not recall the thoughts that may have preceded it.

Intention Memory

Actions and their meanings are stored separately in memory. Otherwise, we would always know exactly what we intend and never suffer the embarrassment of walking into a room and wondering what it was we wanted there. Just as there is a system of mind (and body) that remembers the actions themselves, there must be an

intention memory system

that encodes, stores, and retrieves our thoughts about what we intend. There are three types of intention memory, each corresponding to a point in time at which a person may retrieve the intended meaning or identity of an action. These include

prospective memory

for intention (remembering what one will do),

synchronous memory

for intention (remembering what one is doing), and

retrospective memory

for intention (remembering after acting what one thought one would do).

Prospective memory is involved in remembering plans for action (Brandimonte, Einstein, and McDaniel 1996; Morris 1992). When we devise plans, it is nice to remember them at least long enough to arrive at the time for the action with the plans still in mind. Otherwise, we will simply forget to do what we have intended. In some cases, prospective memory is short-term memory; a person may just think of or rehearse the action for a few moments before it is time to do it. A common example of this is when we are trying to remember the brilliant thing we’ve just thought of to say while some windbag at the other end of the conversation finishes holding forth. Another form of prospective memory covers longer periods (Kvavilashvili 1992), as when we must remember to do something later in the day or week or month (e.g., remember to take medicine), or after some triggering event (e.g., remember to wipe feet after walking in mud).

These preaction ideas of what will be done are often quite easily remembered. In fact, Kurt Lewin (1951) proposed that the things we get in mind to do will each create their own tension systems, packages of psychological discomfort that ride along with them until their associated action is complete and the tension is discharged. He suggested that this is why we often become obsessed with incomplete tasks, coming back to them again and again while we forget things that are completed. The tendency to remember incomplete tasks better than complete ones is the

Zeigarnik effect,

named after Lewin’s student who first tested the idea (Zeigarnik 1927). There is a great deal of research on the phenomenon, and while some of it calls the effect into question, the current view is that memory for unfinished tasks is indeed enhanced compared to memory for those that are finished (Goschke and Kuhl 1993; Marsh, Hicks, and Bink 1998; Martin and Tesser 1989; Wicklund and Gollwitzer 1982).

Enhanced memory for unfinished acts implies a comparative reduction in memory for acts that are finished. In short, performing an action itself tends to erase the memory of the act’s intention. If people will often forget tasks for the simple reason that the tasks have been completed, this signals a loss of contact with their initial intentions once actions are over—and thus a susceptibility to revised intentions. Moreover, people may forget their own intended action as soon as

anyone

completes the act (Lewis and Franklin 1944). The intentions we form and do not yet enact may be quickly forgotten if we believe that other people in our group have done them. All this reveals a remarkable fluidity in our moment-to-moment memory for actions. Initial ideas of what to do can fade rapidly when the action appears to have been done. And this, of course, leaves room for the later invention of what might have been intended.

Synchronous memory for intention is the next type of intention memory. This simply involves remembering the action’s meaning when we are in the process of performing the action. This is convenient for answering the person who asks, “What are you doing?” when we are part way through doing something really strange. But synchronous intention memory is more deeply useful for remembering parts of the action if they are not well-integrated and fluid, for confirming in the course of action whether we’re doing a decent job, and for knowing when we’re done and can go on to the next thing. For that matter, ongoing act memory is also useful for determining whether, when a certain action involves our bodies, we are the ones to whom it can be attributed (e.g., Barresi and Moore 1996). To perform these important services, it is useful to think of intention during action as filling a

current act register,

a memory storage area devoted to the symbolic representation of what we are now doing. With-out such a register, we would not be able to communicate or think about actions unfolding and might lose track of them in mid-course. Meacham (1979) has called this function a matter of “memory for the present.”