The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration (15 page)

Read The Ice Balloon: S. A. Andree and the Heroic Age of Arctic Exploration Online

Authors: Alec Wilkinson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Adventure, #Biography, #History

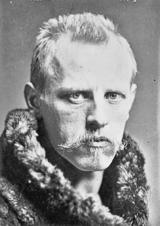

Nansen and Andrée were inspired by visionary theories they were willing to risk their lives to test. Nansen’s method involved refining hundreds of years of efforts by thousands of men. He had read all his predecessors’ accounts and from everyone’s failures he had culled the flaws and corrected them. Nothing could happen to his ship that he wasn’t prepared for. He had practically engineered the risk out of his voyage. Furthermore, having crossed Greenland, he knew how to live outdoors in the Arctic, and not simply in a house with other researchers and plenty of fuel and food.

Different from Nansen, Andrée was a pioneer, a futurist. Men had not been sailing balloons to the Arctic for centuries. Almost nothing of what others had accomplished was helpful to him, unless he came down on the ice. Both men desired acclaim, but the pole figured differently to each of them. Nansen hoped to own a contemporary feat, the discovery of the pole, the permanent farthest north. His attempt had a backward-looking cast, a retinue, a history, annals, and an archive. By better preparation and a brilliant intuition, he hoped to surpass the caravans of sledges and fleets of ships that had tried the same thing he was trying. If the others had only known what I know, he might have thought. Years had to pass before other aviators could look back at Andrée’s attempt and say, If only he had known. Andrée was the first to try a novel task. For Nansen the pole was primary, and for Andrée too, but he also wanted to prove that men could travel long distances in the air. Andrée never wrote down what had moved him so profoundly to hazard his life. His manner was terse and reserved—“He was a typical Swede,” is a remark one often hears about him—and he was not given to confession. He seemed to feel that he had no need to explain himself, or perhaps that confession was undignified. However, Nansen, who had a touch of the extrovert, the buttonholer, and was a natural-born, if slightly fancy, writer, unburdened himself while unsettled one night by the

Fram’s

capricious progress.

“Here I sit in the still winter night on the drifting ice-floe, and see only stars above me,” he wrote. “Far off I see the threads of life twisting themselves into the intricate web which stretches unbroken from life’s sweet morning dawn to the eternal death-stillness of the ice. Thought follows thought—you pick the whole to pieces, and it seems so small—but high above all towers one form.…

Why did you take this voyage

? … Could I do otherwise? Can the river arrest its course and run up hill? My plan has come to nothing. That palace of theory which I reared, in pride and self-confidence, high above all silly objections has fallen like a house of cards at the first breath of wind. Build up the most ingenious theories and you may be sure of one thing—that fact will defy them all. Was I so very sure? Yes, at times; but that was self-deception, intoxication. A secret doubt lurked behind all the reasoning. It seemed as though the longer I defended my theory, the nearer I came to doubting it. But

no

, there is no getting over the evidence of that Siberian driftwood.”

30

The days passed half-idly with tasks and diversions. One night a member of the crew came down to report a more than usually glorious appearance of the aurora borealis, and the rest of them went up to observe it. “No words can depict the glory that met our eyes,” Nansen wrote. “The glowing fire-masses had divided into glistening, many-colored bands, which were writhing and twisting across the sky both in the south and north. The rays sparkled with the purest, most crystalline rainbow colors, chiefly violet-red or carmine and the clearest green.”

On the Christmas of 1893, Nansen thought of the families who would be worrying over his and the crew’s well-being. “I am afraid their compassion would cool if they could look in upon us, hear the merriment that goes on, and see all our comforts and good cheer,” he wrote, and then he reported the day’s menu:

1. Ox-tail soup;

2. Fish-pudding, with potatoes and melted butter;

3. Roast of reindeer, with peas, French beans, potatoes, and cranberry jam;

4. Cloudberries with cream;

5. Cake and marchpane (a welcome present from the baker to the expedition; we blessed that man).

In January he wrote of a plan that he had brooded on for some time and that was now beginning to possess him: to depart from the ship with a companion and on sledges try to reach the pole. “It might almost be called an easy expedition for two men,” he wrote. The plan kept him awake, so that a day later he wrote, “Perhaps my brain is over-tired; day and night my thoughts have turned on the one point, the possibility of reaching the Pole and getting home. Perhaps it is rest I need—to sleep, sleep! Am I afraid of venturing my life? No, it cannot be that. But what else, then, can be keeping me back? Perhaps a secret doubt of the practicability of the plan. My mind is confused; the whole thing has got into a tangle; I am a riddle to myself. I am worn out, and yet I do not feel any special tiredness. Is it perhaps because I sat up reading last night? Everything around is emptiness, and my brain is a blank. I look at the home pictures and am moved by them in a curious, dull way; I look into the future, and feel as if it does not much matter to me whether I get home in the autumn of this year or next. So long as I get home in the end, a year or two seem almost nothing. I have never thought this before.”

Two days later he dreamed that he had reached the pole but had seen only ice, and when people asked what it was like, “I had no answer to give,” he wrote. “I had forgotten to take accurate observations.”

As the new year bore on, he found his thoughts interrupted by images of home. Sometimes when he was absorbed in work, he would hear the dogs bark, then think, Who is coming? before he remembered where he was, “drifting out in the middle of the frozen Polar Sea, at the commencement of the second long Arctic night.”

The sybaritic life of the crew led Nansen to wonder what would happen if they actually had to retreat. He began having every man snowshoe for two hours, then one day they tried hauling a sledge weighing 250 pounds. When one of the men pulled it, “he thought it was nothing at all; but when he had gone on for a time he fell into a fit of deep and evidently sad thought, and went silently home. When he got on board he confided to the others that if a man had to draw a load like that he might just as well lie down at once—it would come to the same thing in the end.”

In November of 1894, on a walk in the evening on snowshoes with Otto Sverdrup, the second in command, Nansen confided his desire to leave the ship for the pole, or as close as he might come to it. Sverdrup, he wrote, “entirely coincided.” Nansen and a companion would leave with twenty-eight dogs and a ton of provisions and equipment. The pole was 483 miles away. Without knowing exactly how the dogs would do, Nansen hoped he could reach it in fifty days. For years he had studied other expeditions and felt “enabled to face any vicissitude of fate.”

Not long after talking with Sverdrup, though, Nansen read again an account of a sledge journey by Payer and felt sobered. “The very land he describes as the realm of Death, where he thinks he and his companions would inevitably have perished had they not recovered the vessel, is the place to which we look for salvation.”

Three tries were necessary for Nansen and Hjalmer Johansen to get away from the

Fram

. The first time the bracing broke on the sledges. The second time Nansen decided that the loads were too heavy. To the degree that the loads included food, they would diminish, but they might also wear the dogs out first. Nansen brought sufficient food for the dogs to last thirty days. After that he planned to feed the dogs on each other, which he calculated would allow fifty more days of travel, “and in that time it seems to me we should have arrived somewhere.”

The false starts allowed them to refine their wardrobe. They began in wolfskin, but it made them sweat, which made the clothes heavier. When they took them off, the garments froze and were difficult to get back on. They decided to wear layers of wool, through which their sweat could evaporate. To protect themselves from wind and “fine-driven snow, which, being of the nature of dust, forces itself into every pore of a woolen fabric,” they wore canvas overalls and a canvas pullover with a hood, “Eskimo fashion.” Their boots they stuffed with sennegrass, which absorbs moisture. At night the sennegrass had to be pulled apart and dried against their bodies. Underneath wolfskin mittens they wore wool ones, which also had to be dried against the skin, and felt hats under hoods. They slept in a double sleeping bag, which was lighter than two single ones and let their bodies share their heat.

“Something which, in my opinion, ought not to be omitted from a sledge journey is a

tent

,” Nansen wrote. His were made from silk and had canvas floors, and he banked them with snow against the wind. In a medicine kit he carried chloroform for an amputation; and cocaine for snowblindness. He also had drops for toothache; needles and silk for stitching cuts; a scalpel; splints and plaster-of-Paris bandages for a broken bone; and “laudanum for derangements of the stomach.”

With three sledges and twenty-eight dogs, he and Johansen got away for good on March 14, 1895, when it was forty-five below zero. For more than a week they made about fourteen miles a day; on their best day they did twenty-one. It never got much warmer. They killed their first dog on March 24. Skinning him was difficult. When the parts were given to the other dogs, many of them refused to eat, but they got over it. “They learned to appreciate dog’s flesh, and later we were not even so considerate as to skin the butchered animal, but served it hair and all,” Nansen wrote.

Even with dogs, sledging was so hard that sometimes they fell asleep as they traveled. They woke when they fell over. Their coats when they sweated froze hard, so that wearing them became like wearing armor, and the coats made a cracking sound when they moved. An arm of Nansen’s coat chafed one of his wrists nearly to the bone. Someone under grave stress often has dreams that continue the text of the day. Nansen would sometimes be awakened by Johansen calling in his sleep to the dogs, “Get on, you devil, you! Go on, you brutes!”

The dogs were used cruelly. “It makes me shudder even now when I think of how we beat them mercilessly with thick ash sticks when, hardly able to move, they stopped from sheer exhaustion,” Nansen wrote. “It made one’s heart bleed to see them, but we turned our eyes away and hardened ourselves.”

By the first week of April, Nansen realized that the ice was too rugged and rough to cross, and that the pole was unreachable. They turned back on April 9. They had been killing the dogs with knives, which was disagreeable; now they tried strangling them. They would walk a dog behind a hummock and use a rope, which took so long that they had to resort to the knife anyway. The ammunition they might have used they had to conserve. Each dog subtracted made hauling the sledges harder.

Two months passed and they were still on the ice. Desperately hungry, Nansen wondered if they should eat the dogs that were left and haul the sledges themselves. The dogs were so exhausted that they sometimes fell down and were dragged in their traces. From the blood of one they made a porridge.

Toward the end of June, they had begun to travel through leads in the kayaks they had brought, with the dogs aboard. A seal rose close to them, and they managed to kill it, which gave them food for a month, raising their spirits. “Here I lie dreaming dreams of brightness,” Nansen wrote.

On July 24, for the first time in two years, they saw something other than “that never-ending white line of the horizon”—land. “We had almost given up our belief in it!” Nansen wrote. They had seen it earlier on several occasions, slightly darker than the ice and rising above it, but had concluded that it was a cloud. It seemed close enough that they thought they might reach it that afternoon. Instead it took thirteen days.