The I Ching or Book of Changes (9 page)

This theory of ideas is applied in a twofold sense. The Book of Changes shows the images of events and also the unfolding of conditions

in statu nascendi

. Thus, in discerning with its help the seeds of things to come, we learn to foresee the future as well as to understand the past. In this way the images on which the hexagrams are based serve as patterns for timely action in the situations indicated. Not only is adaptation to the course of nature thus made possible, but in the

Great Commentary

(pt. II,

chap. II

), an interesting attempt is made to trace back the origin of all the practices and inventions of civilization to such ideas and archetypal images. Whether or not the hypothesis can be made to apply in all specific instances, the basic concept contains a truth.

16

The third element fundamental to the Book of Changes are the judgments. The judgments clothe the images in words, as it were; they indicate whether a given action will bring good fortune or misfortune, remorse or humiliation. The judgments make it possible for a man to make a decision to desist from a course of action indicated by the situation of the moment but harmful in the long run. In this way he makes himself independent of the tyranny of events. In its judgments, and in the interpretations attached to it from the time of Confucius on, the Book of Changes opens to the reader the richest treasure of Chinese wisdom; at the same time it affords him a comprehensive view of the varieties of human experience, enabling him thereby to shape his life of his own sovereign will into an organic whole and so to direct it that it comes into accord with the ultimate tao lying at the root of all that exists.

2.

T

HE

H

ISTORY OF THE

B

OOK OF

C

HANGES

In Chinese literature four holy men are cited as the authors of the Book of Changes, namely, Fu Hsi, King Wên, the Duke of Chou, and Confucius. Fu Hsi is a legendary figure representing the era of hunting and fishing and of the invention of cooking. The fact that he is designated as the inventor of the linear signs of the Book of Changes means that they have been held to be of such antiquity that they antedate historical memory. Moreover, the eight trigrams have names that do not occur in any other connection in the Chinese language, and because of this they have even been thought to be of foreign origin. At all events, they are not archaic characters, as some have been led to believe by the half accidental, half intentional resemblances to them appearing here and there among ancient characters.

17

The eight trigrams are found occurring in various combinations at a very early date. Two collections belonging to antiquity are mentioned: first, the Book of Changes of the Hsia dynasty,

18

called

Lien Shan

, which is said to have begun with the hexagram Kên, KEEPING STILL, mountain; second, the Book of Changes dating from the Shang dynasty,

19

entitled

Kuei Ts’ang

, which began with the hexagram K’un, THE RECEPTIVE. The latter circumstance is mentioned in passing by Confucius himself as a historical fact. It is difficult to say whether the names of the sixty-four hexagrams were then in existence, and if so, whether they were the same as those in the present Book of Changes.

According to general tradition, which we have no reason to challenge, the present collection of sixty-four hexagrams originated with King Wên,

20

progenitor of the Chou dynasty. He is said to have added brief judgments to the hexagrams during his imprisonment at the hands of the tyrant Chou Hsin. The text pertaining to the individual lines originated with his son, the Duke of Chou. This form of the book, entitled the Changes of Chou (

Chou I

), was in use as an oracle throughout the Chou period, as can be proven from a number of the ancient historical records.

This was the status of the book at the time Confucius came upon it. In his old age he gave it intensive study, and it is highly probable that the Commentary on the Decision (

T’uan Chuan

) is his work. The Commentary on the Images also goes back to him, though less directly. A third treatise, a very valuable and detailed commentary on the individual lines, compiled by his pupils or by their successors, in the form of questions and answers, survives only in fragments.

21

Among the followers of Confucius, it would appear, it was principally Pu Shang (Tzu Hsia) who spread the knowledge of the Book of Changes. With the development of philosophical speculation, as reflected in the Great Learning (

Ta Hsüeh

) and the Doctrine of the Mean (

Chung Yung

),

22

this type of philosophy exercised an ever increasing influence upon the interpretation of the Book of Changes. A literature grew up around the book, fragments of which—some dating from an early and some from a later time—are to be found in the so-called Ten Wings. They differ greatly with respect to content and intrinsic value.

The Book of Changes escaped the fate of the other classics at the time of the famous burning of the books under the tyrant Ch’in Shih Huang Ti. Hence, if there is anything in the legend that the burning alone is responsible for the mutilation of the texts of the old books, the

I Ching

at least should be intact; but this is not the case. In reality it is the vicissitudes of the centuries, the collapse of ancient cultures, and the change in the system of writing that are to be blamed for the damage suffered by all ancient works.

After the Book of Changes had become firmly established as a book of divination and magic in the time of Ch’in Shih Huang Ti, the entire school of magicians (

fang shih

) of the Ch’in and Han dynasties made it their prey. And the yin-yang doctrine, which was probably introduced through the work of Tsou Yen,

23

and later promoted by Tung Chung Shu, Liu Hsin, and Liu Hsiang,

24

ran riot in connection with the interpretation of the

I Ching

.

The task of clearing away all this rubbish was reserved for a great and wise scholar, Wang Pi,

25

who wrote about the meaning of the Book of Changes as a book of wisdom, not as a book of divination. He soon found emulation, and the teachings of the yin-yang school of magic were displaced, in relation to the book, by a philosophy of statecraft that was gradually developing. In the Sung

26

period, the

I Ching

was used as a basis for the

t’ai chi t’u

doctrine—which was probably not of Chinese origin—until the appearance of the elder Ch’êng Tzu’s

27

very good commentary. It had become customary to separate the old commentaries contained in the Ten Wings and to place them with the individual hexagrams to which they refer. Thus the book became by degrees entirely a textbook relating to statecraft and the philosophy of life. Then Chu Hsi

28

attempted to rehabilitate it as a book of oracles; in addition to a short and precise commentary on the

I Ching

, he published an introduction to his investigations concerning the art of divination.

The critical-historical school of the last dynasty also took the Book of Changes in hand. However, because of their opposition to the Sung scholars and their preference for the Han commentators, who were nearer in point of time to the compilation of the Book of Changes, they were less successful here than in their treatment of the other classics. For the Han commentators were in the last analysis sorcerers, or were influenced by theories of magic. A very good edition was arranged in the K’ang Hsi

29

period, under the title

Chou I Chê Chung

; it presents the text and the wings separately and includes the best commentaries of all periods. This is the edition on which the present translation is based.

3.

T

HE

A

RRANGEMENT OF THE

T

RANSLATION

An exposition of the principles that have been followed in the translation of the Book of Changes should be of essential help to the reader.

The translation of the text has been given as brief and concise a form as possible, in order to preserve the archaic impression that prevails in the Chinese. This has made it all the more necessary to present not only the text but also digests of the most important Chinese commentaries. These digests have been made as succinct as possible and afford a survey of the outstanding contributions made by Chinese scholarship toward elucidation of the book. Comparisons with Occidental writings,

30

which frequently suggested themselves, as well as views of my own, have been introduced as sparingly as possible and have invariably been expressly identified as such. The reader may therefore regard the text and the commentary as genuine renditions of Chinese thought. Special attention is called to this fact because many of the fundamental truths presented are so closely parallel to Christian tenets that the impression is often really striking.

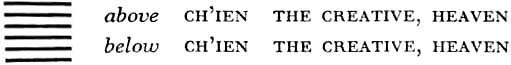

In order to make it as easy as possible for the layman to understand the

I Ching

, the texts of the sixty-four hexagrams, together with pertinent interpretations, are presented in book I. The reader will do well to begin by reading this part with his attention fixed on its main ideas and without allowing himself to be distracted by the imagery. For example, he should follow through the idea of the Creative in its step-by-step development—as delineated in masterly fashion in the first hexagram—taking the dragons for granted for the moment. In this way he will gain an idea of what Chinese wisdom has to say about the conduct of life.

The second and third books explain why all these things are as they are. Here the material essential to an understanding of the structure of the hexagrams has been brought together, but only so much of it as is absolutely necessary, and as far as possible only the oldest material, as preserved in the Ten Wings, is presented. So far as has been feasible, these commentaries have been broken down and apportioned to the relevant parts of the text, in such a way as to afford a better understanding of them—their essential content having been made available earlier in the commentary summaries in book I. Therefore, for one who would plumb the depths of wisdom in the Book of Changes, the second and third books are indispensable. On the other hand, the Western reader’s power of comprehension ought not to be burdened at the outset with too much that is unfamiliar. Consequently it has not been possible to avoid a certain amount of repetition, but such reiteration will be of help in obtaining a thorough understanding of the book. It is my firm conviction that anyone who really assimilates the essence of the Book of Changes will be enriched thereby in experience and in true understanding of life.

R. W.

THE

TEXT

PART I