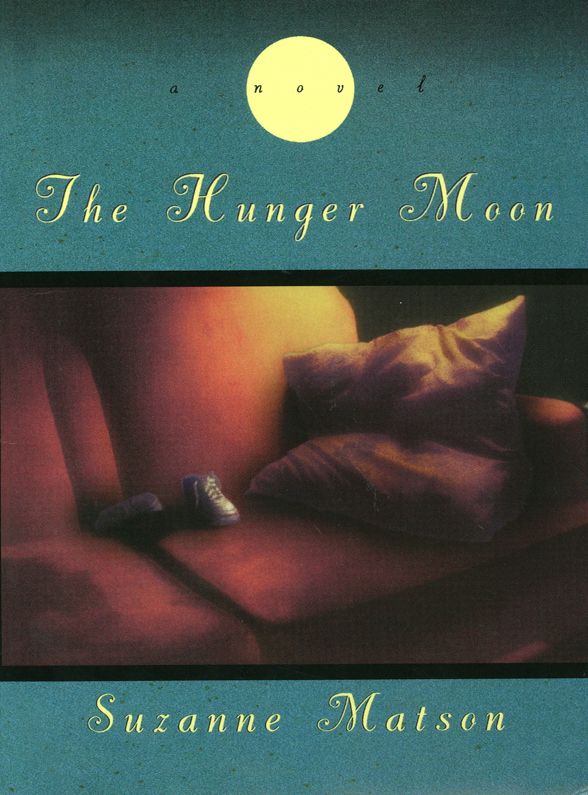

The Hunger Moon

Authors: Suzanne Matson

A

LSO BY

S

UZANNE

M

ATSON

Durable Goods

(poems)

Sea Level

(poems)

FOR JOE, NICK, AND HENRY

Contents

R

ENATA WAS HAPPIEST DRIVING

, knowing she was

en route

. She loved poring over road maps to find towns with names like Knockemstiff, Pep, Peerless, and Bean Blossom. She loved stopping for meals at diners with EAT outlined in neon against the evening sky, and finding motels at night that had a little angled parking space right in front of each blue or green or orange front door. She appreciated the way the roadside markers changed colors and typography with the states, so that she always knew she was getting someplace new.

It was different now, traveling with a baby, but in a way it was even better—just the two of them, the car a little world in which they were perfectly alone. Charlie was so good. Sometimes, when they had driven for more than an hour and she couldn’t hear his soft snores, she reached one arm in back of her to pat his head where he lay in his rear-facing infant seat. Even that wasn’t enough; she needed to trail her fingers gently down the front of his face until she reached his mouth, parted slightly in sleep. Only then, when he’d latch on to her fingertip and start sucking, was she reassured. “Just checking, pal,” she’d tell him.

Charlie liked the road as much as she did. For the two months that they had been drifting eastward across the country, Charlie

had grown to sleep and wake according to the car’s engine, enabling Renata to regulate his daytime schedule perfectly. It was when they stopped in some town for a few days so Renata could catch her breath that Charlie seemed disoriented, and forgot how to nap. Those days Renata sometimes took elaborate sightseeing drives to make him feel at home.

At night in their motel rooms she made the baby a nest of pillows and blankets on one side of their queen-size bed; she didn’t think she should indulge in the pleasure of holding him close to her all night. The few nights she had given in and cradled him next to her, he had nursed on and off continually, like a puppy. Somehow that seemed too decadent; she had read that it was better for the baby to have regular feeding times. Regularity in his life would let him know that he could count on things, and this was important to her.

Soon he would be able to roll off the side of the bed, and so she would need to get one of those portable cribs. Renata had so far bought as little baby gear as possible. She liked the feeling of their lightness: her one large duffel with both their clothes, the car seat, the folding stroller. She stopped two or three times a week at a Laundromat to do their laundry while Charlie dozed in the stroller. He liked the hum of the washing machines almost as much as he liked riding in the car, and when she scooped their clothes out of the dryer, she would lay the baby in the midst of them to kick and chuckle in the warm pile.

People were friendly in the middle of the country; they often wanted to know where Renata was headed with such a young baby, and wasn’t she afraid to drive alone? In Nevada she had bought herself a thin wedding band for sixty-five dollars at a pawnshop. Town by town she honed her story until she had a version that she liked: her husband was in the military and she was moving to a town nearer his base. Their furniture was being transported separately. She had driven rather than flown so that she could stop on the way and spend time with the baby’s grandparents. The location of the base and the grandparents changed

according to what part of the country Renata was in, but it was always distant enough so that locals wouldn’t ask her questions she couldn’t answer.

Having a baby made people considerate and respectful toward her. Men who before would have come on to her now simply held doors wide for the stroller or helped to raise it up over a curb. Women who would have watched her like a hawk because of their men now smiled and asked how old the baby was. She was welcomed into an invisible country of mothers that behaved the same wherever she went. She was given nice big booths by restaurant hostesses to accommodate the car seat; waitresses dandled the baby while she paid the check; and one young mother she met in a Nebraska laundromat even gave Charlie a darling little overall fresh from the dryer that she said her own baby boy was just out of.

As long as they kept moving, Renata felt that nothing bad could ever touch them, so she drove from Eugene to Boise, down to Reno then Flagstaff, up to Salt Lake City and Billings, on to Casper and Rapid City, then through North Platte via Valentine, and so on. She didn’t like interstates because they were too straight and too fast. Renata looked for long cuts, wrong turns, detours, and backtracks. She wasn’t in a hurry. She had enough money in her account for now, and with her bank card she could get at it just about anywhere. The future would take care of itself, Renata felt sure, just as soon as she got them to Massachusetts. But they had plenty of time until then, and she thought there might never be days like this again, a perfect union of Charlie and Renata, with no one to interfere and nothing to take her attention away from him. Driving, her foot keeping the accelerator a conservative fifty-five, Renata had time to plan things as she stared at the horizon, and time even to go over the important episodes of her life, rehearsing the ways she would make sure Charlie would have a better start than she had.

She thought she made a pretty good mother, enough to make up for the fact that her baby would never know his natural father.

Charlie’s father did not know he had a child. They had gone together for a year while Renata was waitressing in Venice, California. In the early months of her pregnancy she broke it off and went to live in Oregon with her sister until the baby was born.

Charlie’s father, Bryan, was not a bad guy; he was funny, and handsome, and romantic. But he was living a prolonged adolescence on the beach in Venice—bartending just enough to pay the rent in an old house he shared with four other guys. He usually ate for free at Renata’s beachfront café when her manager wasn’t around, and he drank for free at his own restaurant on his nights off. If they did anything else, Renata often found herself picking up the check, or one of his friends paid. His lack of responsibility made her impatient, but that wasn’t why she had left without telling him they were having a baby.

Bryan was marked for tragedy. He was literally marked, with a puckered scar running down his back from when his mother had tried to kill them both by jumping from the roof of their house when he was a baby. She hadn’t succeeded then, although she had done enough damage to herself to require long hospital stays and painkiller prescriptions that she stockpiled until she had enough pills to finish the job. Bryan had been eighteen months old at the time of the big leap, as he liked to call it. One of the guardian angels in charge of infants must have swooped down just in time to cradle him gently above the ground while his mother’s bones shattered under him. Actually, they had found him wailing inside her unconscious arms, which embraced him so tightly that he had to be pried from her by two strong men. A row of shrubbery alongside the house had broken their fall. Bryan’s only injury had been the open gash on his back, which required eighteen stitches, one for every month of his life. No one ever told him what it was on the way down that had cut him open; but the uncles and aunts he grew up with, rotating among their families in six-month shifts, always reminded him how lucky he was to have survived with only the single wound.

Renata saw it differently. She believed Bryan’s survival to be a

reprieve, and a harbinger of some final fall that lay in store for him. This was not mere superstition, brought on by the awe she felt every time she imagined the darkness surrounding Bryan’s mother before she jumped, but information coming from Bryan himself. She had at first been attracted to his easygoing humor, his perpetual air of having just come from the beach, the fine premature creases around his eyes from being tanned year-round since he was a child. It was only after they had become lovers that she discovered that grief was his only true companion, the one he was already married to.

The first night she heard it, she woke in a cold dread, wondering what evil had entered the room to be with them, what sobbing ghost. As her mind cleared and her eyes adjusted to the darkness, she realized that the moaning was coming from the man she was in bed with, whose anguished face bore no resemblance to her laid-back boyfriend. Gradually she became used to Bryan’s dreams, of which he claimed he remembered nothing the next morning, but she could never get used to the loneliness of making love with him. When he was inside her she would open her eyes to see him looking through her. His bereft stare was enough to bring tears to her own eyes. At that point the joking Bryan would return to her, solicitous and kind. She never told him that she was crying on his behalf, knowing that she could never hold him securely enough to convince him he was not falling.

Renata had left because the bottomless nature of Bryan’s sadness scared her, and once you gave a child a father, you couldn’t unmake the link. She knew how it was with bad parents. You kept them, for better or for worse; and whether they did right by you or not, they were yours to haul around for life. With Bryan forming the third point of their triangle, there would be an unstable corner, like a table that wobbled, always worrying the back of her mind when she put something weighty on it. She would rather raise her daughter by herself—for Renata had been certain that she would have a girl. She had pictured a smaller Renata, the same dark hair as her own, which she would comb and braid for her

daughter as her mother had done when she was a girl.