The House of Rothschild (53 page)

Read The House of Rothschild Online

Authors: Niall Ferguson

It may of course be asked why she and Lionel so desperately wished their sons to be academically successful: despite Alphonse’s faith in “college education,” there is no obvious reason why an honours degree from Cambridge would have been an advantage in the City. On the other hand, the proportion of City bankers educated at public school, Oxford or Cambridge rose markedly in the course of the nineteenth century. Charlotte urged Leo to “find an hour or two in the course of the day to write English exercises ... [as] it would enable you, even in the practical routine of New Court life to draw up contracts, make statements upon important financial transactions, and furnish those great papers, which should really not be drawn up by clerks.” But her real aim, one suspects, was less to prepare Leo for “the real business of life... at New Court” than to give him the classical education she herself had missed and craved—and in so doing to add another trophy to the Rothschild collection. A degree, like a seat in the Commons, had no functional value to the Rothschilds as bankers, but was a prize in their campaign for complete social parity with the Gentile elite. “University honors,” she lectured her youngest son in 1865, “are excellent credentials; if they do not prove the winner to be possessed of great gifts and remarkable talents, they prove that he has applied and exerted himself to acquire knowledge, that he has a firm will, energy, assiduity and perseverance, and those are valuable qualities.” Two years later, she reverted to the same theme:

distinctions achieved at the University must be a passport, a letter of introduction to the favorable opinion of the world.—In your own family, in business, in society, in the House of Commons, at home and abroad, and in all classes of the community—a man who has taken a good degree at Cambridge or Oxford is more highly thought of, and this good opinion acts as an encouragement to every useful exertion throughout life.

She and Lionel were furious when Leo lent some money to a friend, for this was a betrayal of social origins which Cambridge was partly supposed to efface:

I always thought you had common sense, and never thought you silly enough to advance five hundred pounds to a stupid scamp, who has hardly as many shillings in the world that he can call his own. [D]anger ous as it is for all individuals to lend money—it is far more so for any one, who bears the name of Rothschild.—Indeed I have not expressed myself correctly; it is absolutely impossible that any person, any member, great or insignificant[,] of our family should think, for one single instant of anything so absurd.—the loan of money is perfectly certain to change a friend into an enemy.—Nobody would think of returning money to a Rothschild, but would shun the lender in consequence, and probably for ever—and we might sacrifice enormous sums without doing any good, or giving any pleasure.—I have never in the whole course of my existence, lent any one a single six pence;—if a gift can be of service, well and good; is [sic] the petitioner too proud to accept five or ten pounds let him, if he can refund the money, give it to a charity. I have acted upon that principle all my life—and thank God, have no imprudence to regret...

PS Why can’t you lock yourself up ... and keep away from all the idle, lazy, good-for-nothing young men, who infest Cambridge, and steal your precious time, your good intentions and your energy away[?]

But academic credentials eluded this generation. At best Natty did not disgrace himself at Cambridge; his younger brothers did rather worse. Charlotte may have been anxious that Alfred “should visit Cambridge and distinguish himself there,” but after only a single year (1861-2) he was taken ill and never returned. Efforts were made to introduce Alfred to the world of philanthropy and politics: under Anthony’s supervision, he sat on a City committee “for the Relief of distress” in the hard winter of 1867. “I hope and believe that your brother will attend,” wrote his anxious mother. “It will do [Alfred] good to accustom himself to popular meetings, and, in time, he may perhaps become reconciled to the idea of entering parliament, which, at present, seems so repugnant to his tastes.” In 1868 he became the first Jew to be elected to the Court of Directors of the Bank of England, another appointment he owed entirely to his family rather than his ability. But he conspicuously failed to make this the position of influence which Alphonse made his role as regent of the Banque de France.

11

Alfred lived the life of a

fin

de

siècle

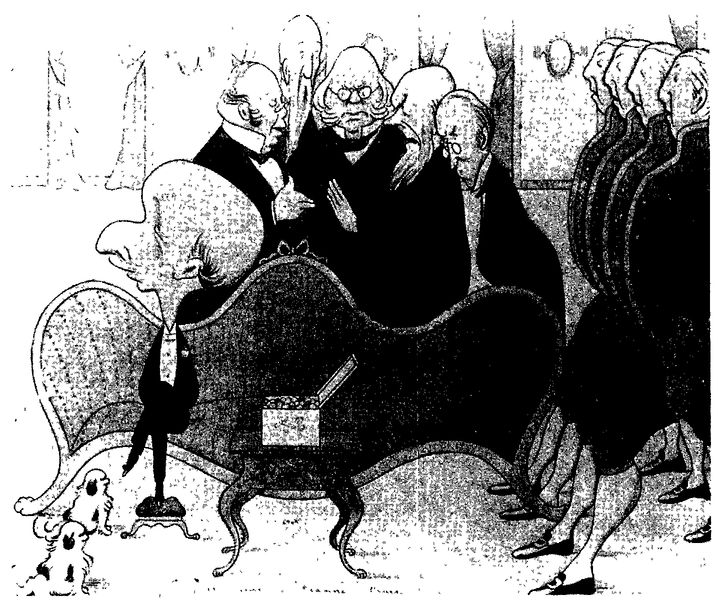

aesthete, at once effete and faintly risque. Max Beerbohm’s cartoon—

A quiet evening in Seymour Place. Doctors consulting whether Mr Alfred may, or may not, take a second praline before bedtime

—captures the former quality (see illustration 7.i). So does Alfred’s somewhat feeble

bon mot

when another Bank of England director (reflecting on Anselm’s will) “suggested that in fifty years the Times would announce that your brother had left all Buckinghamshire. ‘You make a mistake’ was the reply to a very unseemly remark, ’believe me I shall leave a great deal more, I shall leave the world.‘ ”

11

Alfred lived the life of a

fin

de

siècle

aesthete, at once effete and faintly risque. Max Beerbohm’s cartoon—

A quiet evening in Seymour Place. Doctors consulting whether Mr Alfred may, or may not, take a second praline before bedtime

—captures the former quality (see illustration 7.i). So does Alfred’s somewhat feeble

bon mot

when another Bank of England director (reflecting on Anselm’s will) “suggested that in fifty years the Times would announce that your brother had left all Buckinghamshire. ‘You make a mistake’ was the reply to a very unseemly remark, ’believe me I shall leave a great deal more, I shall leave the world.‘ ”

7.i: Max Beerbohm,

A quiet evening in Seymour Place. Doctors consulting whether Mr Alfred may, or may not, take a second praline before bedtime.

A quiet evening in Seymour Place. Doctors consulting whether Mr Alfred may, or may not, take a second praline before bedtime.

Leopold (Leo) was, if anything, an even greater disappointment, if only because Lionel and Charlotte pinned their last remaining hopes for academic success on him. Despite—perhaps because of—a relentless bombardment of parental exhorta- tions and reproofs throughout his Cambridge career, Leo had to postpone his Little Go, was marked down for his limited knowledge of Christian theology and scraped a third in his final exams. His mother feared that he would “pass for the most ignorant, most thoughtless, and most shallow of human beings” and was mortified to hear her friend Matthew Arnold say “that he cannot believe you are or ever will be a reading man, as you talked of going to Newmarket which he thought was a pity, as you seemed to him made for better things. I assure you I am not exaggerating—and that Mr. Arnold reverted three times to the race-course.” Lionel, who like Charlotte had hoped to see him in “Class I and very high up,” later commented acidly: “Your examiners were quite right in saying you were a good hand at guessing.” It is hard not to sympathise with Leo and his brothers. “Dear Papa does not expect any so-called news from your pen,” ran a typical letter from home in 1866,

but he wishes to know how you spend your time, at what hour you separate yourself from your beloved pillow, when you breakfast, with a description of the breakfast-table and of the ingredients of that earliest meal, how many hours you devote to serious conscientious studies, divided into preparations and lessons, what authors you are reading in Greek and Latin, in prose and poetry, how much leisure you devote to lighter reading such as modern poetry and history, how much, on how little to still lighter literature, such as romances and novels, in French and English—how much exercise you take.

Any university teacher knows how counter-productive this kind of parental pressure can be. If Leo preferred to idle away his time in the company of “idle, lazy, good-for-nothing young men” like Cyril Flower,

12

it may partly have been a reaction against his mother and father’s incessant lecturing. The more desperately Charlotte urged him to “study something—drawing, painting, music, languages”—the more his interests turned elsewhere, principally to horse-racing.

13

In the end, the only “English” Rothschild of this generation to secure a university degree (in law) was Nat’s son James Edouard, who grew up and studied in France. It can hardly be claimed that he was an advertisement for higher education. An ardent bibliophile who accumulated a large collection of rare books, obsessively excluding volumes with the slightest blemish, he is said to have committed suicide in 1881 at the age of thirty-six, perhaps the first Rothschild in whom the desire to accumulate valuable objects took on a dysfunctional character.

12

it may partly have been a reaction against his mother and father’s incessant lecturing. The more desperately Charlotte urged him to “study something—drawing, painting, music, languages”—the more his interests turned elsewhere, principally to horse-racing.

13

In the end, the only “English” Rothschild of this generation to secure a university degree (in law) was Nat’s son James Edouard, who grew up and studied in France. It can hardly be claimed that he was an advertisement for higher education. An ardent bibliophile who accumulated a large collection of rare books, obsessively excluding volumes with the slightest blemish, he is said to have committed suicide in 1881 at the age of thirty-six, perhaps the first Rothschild in whom the desire to accumulate valuable objects took on a dysfunctional character.

Of course, Leo’s devotion to the Turf had a precedent. His uncle Anthony had been a keen racegoer in his youth and his uncle Mayer was even more of an equine enthusiast. Indeed, it was said of Mayer in the 1860s that he was “so constantly away and amusing himself that his partners’ and nephews’ ... softly modulated voices had become inaudible to him.” In “the Baron’s Year” of 1871, his horses won four of the five “classic” races: the Derby, the Oaks, the Thousand Guineas and the St Leger. Eight years later, Leo himself was the owner of the Derby winner when his little-known horse Sir Bevys beat the Earl of Rosebery’s Visconti into third place (though Leo had used the bogus name “Mr Acton” to conceal his identity). He nearly won the Derby again with St Frusquin in 1896 (the horse came second to the Prince of Wales’s Persimmon) and did win it a second time in 1904 with St Amant. This was a symbol more of continuity than of decadence, then; the fact that he could earn as much as £46,766 in prize money in a single season may even be taken as a sign of traditional acumen. At the same time, sport was now an integral part of City life—witness the cricket match between a Stock Exchange XI and Leo’s own XI in 1880, a classic example of late-Victorian corporate hospitality. Another novelty was Leo’s enthusiasm for motor cars, the supreme rich man’s toy of the

fin-de-siècle.

There was also something new about the extravagance of having a racehorse like St Frusquin modelled in silver by Fabergé (with twelve bronze replicas for friends).

fin-de-siècle.

There was also something new about the extravagance of having a racehorse like St Frusquin modelled in silver by Fabergé (with twelve bronze replicas for friends).

The sons of Anselm evinced similar tendencies. The eldest, Nathaniel (b. 1836), studied at Brünn but quarrelled bitterly with his father, who considered him spendthrift and financially incompetent. Ferdinand (b. 1839) showed even less interest in the family business, preferring to spend his time in England, where both his mother and wife had been born and raised. He was quite candid about his lack of the most important of Rothschild traits. “It is an odd thing,” he wrote forlornly in 1872, “but whenever I sell any stock it is sure to rise and if I buy any it generally falls.” That left Salomon Albert (b. 1844), usually known in the family as “Salbert.” Albert had studied at Bonn as well as at Brünn “with great energy, perseverance, devotion and success” but, when his father was taken ill in 1866, seemed “overanxious, over-alarmed, dreadfully frightened at [the prospect of] his undivided responsibility” for the Vienna house. When Anselm finally died eight years later, he left most of his real estate and art collection to Nathaniel and Ferdinand and only his share of the family partnership to Albert, who regarded himself as having been “not very well treated.” In short, Albert had to be forced into the business,

faute

de

mieux.

faute

de

mieux.

In Paris, of course, it was the third generation rather than the fourth which came to power after James’s death in 1868. Yet here too there seemed to be a falling off. Part of the problem was that James had been such a domineering father. Feydeau commented that James had “never delegated the smallest part of his enormous responsibility to his children or his employees.” “What submissiveness on the part of his sons,” he marvelled ironically. “What a feeling of hierarchy! What respect! They would not permit themselves, even with respect to the most minimal transaction, to sign—with that cabalistic signature which binds the house—without consulting their father. ‘Ask Papa,’ you are told by men of forty, who are almost as experienced as their father, no matter how trifling the inquiry you address to them.” The, Goncourts noticed the same tendency.

The eldest son Alphonse—who was forty-one when his father died—seems to have withstood the years of paternal dominance the best, suggesting once again that it was the first-born of the third generation who was most likely to inherit or imbibe the mentality of the Judengasse. Educated at the College Bourbon, Alphonse had an enthusiasm for art (and for stamp-collecting), but he never allowed these interests to distract him from the serious business of the bank. In March 1866, he was asked by a friend after dinner “why, when he was so rich, he worked like a negro to become more so. ‘Ah!’ he replied, ‘You don’t know the pleasure of feeling heaps of Christians under one’s boots.’ ” Like Lionel and Anselm, he took pleasure in austerity: when he was observed in 1891 taking the train from Nice to Monte Carlo (where he “played very little”) it was his very ordinariness which was remarkable: “He waits for the train sitting on a bench, like any common mortal, and smoking his cigar”—albeit watched like a hawk by the conductor who stood ready to open the door of his compartment as soon as he showed any sign of boarding. Gustave too shared many of the attitudes of the older Rothschilds. As Mérimée remarked wryly when he dined with him and his wife at Cannes in 1867, “he seemed to have a good deal of religion and to think on the subject of money like the rest of his house.” When he later heard that Gustave had impulsively left for Nice, he had no doubt he had sub-let his villa in Cannes at a profit.

It was James’s younger sons who struggled. The Goncourts observed in 1862 how imperiously Salomon James (b. 1835) was treated by his father. After losing a million francs at the bourse, he:

received this letter from the father of millions: “Mr Salomon Rothschild will go to spend the night at Ferrières, where he will receive instructions which concern him.” The next day, he received the order to leave for Frankfurt. Two years passed in the counting house there; he believed his penance was over; he wrote to his father who replied: “Mr Salomon’s business is not yet finished.” And a new order sent him to spend a couple of years in the United States.

Other books

Crazy in the Kitchen by Louise DeSalvo

Battle Story by Chris Brown

Wounds - Book 2 by Ilsa J. Bick

In the Wind by Bijou Hunter

Commando by Lindsay McKenna

Touchstone by Laurie R. King

Mafia Captive by Kitty Thomas

Dark World (Book I in the Dark World Trilogy) by Q. Lee, Danielle

Angel Dust by Sarah Mussi

Awoken by Timothy Miller