The History Buff's Guide to World War II (23 page)

Read The History Buff's Guide to World War II Online

Authors: Thomas R. Flagel

The long-awaited invasion of Europe began with the landings at Normandy on June 6,1944.

Unfortunately for the Allies, post-landing planning was not nearly as precise. Secondary objectives were not clearly defined. The countryside was a maze of hedgerows, making offensive coordination nearly impossible. But a solid beachhead had been established in Nazi-occupied territory, and the end of the war in Europe could be measured in months rather than years.

Often seen in the United States as a primarily American operation, the Allied airborne and landing troops on D-day included eighty-three thousand Americans plus eighty-eight thousand British and Canadians.

9

. BATTLE OF THE BULGE (DECEMBER 16, 1944–JANUARY 16,1945)

Though Hitler visualized launching grand counterattacks until the day he died, his last true offensive mimicked his greatest battlefield success. The outcome, however, did not.

Pulling resources from the eastern front, against the advice of his senior staff, Hitler ordered three panzer armies into the Allied lines on Germany’s western border. Assembling in only five days, cloaked under cloudy skies and frigid weather, the Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh German Armies rammed directly into the middle of the Allied front, once again using the “impassible” Ardennes as the entry point.

German forces stalled the Allied offensive with a reprise of the invasion of France in a surprise attack through the Ardennes in December 1944.

By Christmas Eve the German bulge had reached sixty-five miles into the Allied lines. But clearing skies brought five thousand Allied aircraft and a tenacious American counterattack. The ill-prepared Germans lacked the fuel and ammunition for an extended fight and rapidly lost everything they had gained.

On a map, the front line looked almost exactly the same after the battle as before it started. But the fight involved one million men and cost the Allies more than 70,000 casualties. The Germans suffered more than 120,000 dead, wounded, or missing. The Second Ardennes also critically weakened Germany’s east and west fronts, expediting the downfall of the Third Reich. Most likely, Hitler’s late commitment to the Ardennes campaign allowed for greater Soviet progress into Central Europe than would have otherwise been achieved.

Allegedly, the German commanding officer, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, had so little faith in the Ardennes offensive, he put his second in command at the head of affairs and spent the first part of the battle reading novels and drinking cognac.

10

. BERLIN (APRIL 16–MAY 2, 1945)

By mid-January 1945, the Allies in the West had recovered lost ground from the Bulge, and the Soviets to the east had launched their last final offensive in a driving snowstorm outside Warsaw. The vise was beginning to close.

In rapid succession, Warsaw fell, or what was left of it. In a matter of weeks the Soviets reached the Oder River, the old German border, and began to spread north and south to consolidate their gains. Terrorized German citizens fled to Berlin, only to be struck by thousand-bomber raids. February 13 brought the fall of Budapest and the Dresden fire bombings. By the ides of March the Americans and British began crossing the Rhine.

Then on April 16, four days after the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Soviets entered Germany with more than two million soldiers and began to destroy everything. Looting became widespread, as did murder and arson. The Soviets also conducted rampant molestation. It is believed that 80 percent of all females in and around Berlin were brutally and repeatedly violated by Soviet troops.

90

The savagery continued into the city center. Artillery battered the remnants of the capital as the Red Army entered from the north and south. The Reichstag was their target, not the Chancellery four hundred yards away, under which Hitler committed suicide on April 30.

On May 7 Gen. Alfred Jodl signed an unconditional surrender to the Allies at Eisenhower’s headquarters in Reims, France. Angered that the Americans and British should receive capitulation before the Soviets, Stalin demanded an “official” surrender ceremony be held the following day in Berlin.

Yet one of the most significant events in the battle for the German capital occurred nearly a month before its downfall. On April 11, General Eisenhower ordered the western Allies to halt along the Elbe River, just seventy miles from Berlin, and allow the Soviets to enter the city first. Done to prevent possible deaths from friendly fire between the east and west fronts, and to concentrate on taking as much of southern Germany as possible, Eisenhower’s decision infuriated the British and a fair number of Americans. The disappointment soon fostered a widely held belief that the U.S. high command “gave up” Berlin to placate Stalin and thereby lost the first pivotal battle in the Cold War.

91

Before the fall of Berlin, friendly fire had occurred between the Soviets and the Americans. On March 18, near the German capital, U.S. fighter pilots engaged eight “Focke-Wulf 190s.” The single-engine fighters were in fact Soviet air force aircraft, six of which were lost, resulting in two deaths.

MOST SIGNIFICANT BATTLES: ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

There is a tendency in the United States to reduce the Pacific and Asian theaters to Honolulu and Hiroshima and to concentrate instead on the war in France and Germany. But a eurocentric view greatly skews the big picture.

In spite of a “Germany First” strategy, the United States had already engaged in a score of naval engagements, conducted its first offensive, bombed Tokyo, and suffered ten thousand dead in the Pacific before ever launching its first land assault on Nazi-held territory (which in fact was into French Morocco and Algeria). For the rest of the world, the war in Asia and the Pacific involved twice the number of people, was almost three years longer in duration, and covered four times more of the surface of the planet than did the conflict in Europe and North Africa.

The region’s battles included the bloodiest in U.S. Navy history, the bloodiest in U.S. Marine history, the longest retreat in British military history, plus numerous incidents of Japanese forces experiencing casualties of 100 percent.

Within these milestones were many thousands of clashes, most lasting a few hours and others enveloping several months. Listed in chronological order are the ten most significant military clashes among them in terms of strategic, economic, and political consequences in the region.

1

. SHANGHAI (AUGUST 13–NOVEMBER 9, 1937)

To the surprise of his country and the Japanese military, Nationalist leader C

HIANG

K

AI

-S

HEK

did not offer concessions to Japan after the C

HINE

I

NCIDENT

along the Marco Polo Bridge. Normally he would back down after such military “disturbances” with Japan’s Manchurian Kwantung Army.

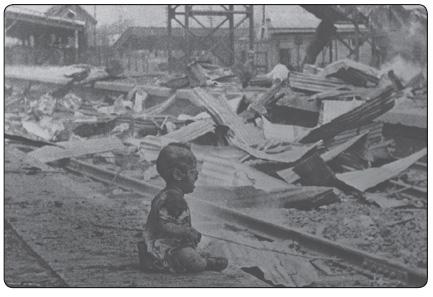

Instead, Chiang sent troops into the multinational city of Shanghai. The move was in clear violation of an agreement (one of many with Japan) to keep the area demilitarized. The unarmed city soon became host to 400,000 Nationalist Chinese and 200,000 Japanese troops, slamming away at each other with artillery, bombs, and small-arms’ fire. Unburied bodies filled the streets. Blocks burned to the ground. Fighting lasted for nearly three months.

A child wails amid the debris after the Japanese bombed Shanghai.

When the Japanese threatened to cut off his line of retreat, Chiang directed his men to remain in the city, dooming his best and most loyal troops. Only at the last moment did he order a withdrawal, which quickly turned into a terrorized rout westward to Nanking.

The Japanese lost some 70,000 men. Chiang lost at least 180,000. The number of civilians killed or maimed has never been accurately calculated. Chiang’s wish for international intervention went unfulfilled, and the war in Asia had officially begun.

At the start of the battle for Shanghai, the Nationalist Chinese air force tried to bomb Japanese ships moored in the city along the Yangtze River. The bombs overshot the targets and struck a busy shopping district, killing 728 civilians.

92

2

. PEARL HARBOR, OAHU (DECEMBER 7, 1941)

Strategically, Oahu loomed on the Japanese navy’s left flank. Imperial warships could not hope to move south against resource-rich countries until the military threat to the east was neutralized. From this logic, Japan’s naval high command began to view a preemptive strike against the American fleet at P

EARL

H

ARBOR

as its best chance for success everywhere else.

Planned nearly a year ahead of time and set in motion while diplomatic exchanges continued between the two countries, the Japanese attack on U.S. naval and air installations in Hawaii went better than even the most optimistic had hoped. Shielded by a series of storms on its approach, a flotilla of eighty-eight warships sailed undetected on a five-thousand-mile voyage, launched some 350 planes, and retrieved all but 29 aircraft. In return, the attack crippled nearly every U.S. battleship in the Pacific, sank or damaged a number of other ships, and destroyed or damaged nearly three-quarters of all military aircraft on the island of Oahu. For the U.S. Navy, the first day of the war was the worst, with more than 2,100 dead.