The Harlot by The Side of The Road: Forbidden Tales of The Bible (53 page)

Read The Harlot by The Side of The Road: Forbidden Tales of The Bible Online

Authors: Jonathan Kirsch

The Septuagint also gives us some of the familiar divisions of the biblical text into two paired books. The Book of Samuel, for example, can be accommodated on a single scroll when rendered in Hebrew, which contains only consonants and takes up much less space on a sheet of paper or parchment than the same text in a language that includes both vowels and consonants. The Septuagint, by contrast, required

two

scrolls to accommodate the Greek translation of the Book of Samuel, and so the translators divided the text into what we know today as the First and Second Books of Samuel. The same technique is preserved in other biblical works that are conventionally divided into first and second volumes in modern Bibles.

5

Late in the biblical era, Aramaic replaced Hebrew as the day-to-day language of the Holy Land, and so the original Hebrew text was translated into Aramaic. Several Aramaic translations, each one known as a Targum, have survived from antiquity, and they reveal that the early translators felt at liberty to embroider upon and explain the biblical text, sometimes to avoid embarrassing or difficult-to-explain passages and sometimes to highlight a particular moral or theological point of view. Some scholars regard the Targums as a kind of “rewritten Bible” rather than a faithful rendering of the original Hebrew text. Still, the sense of freedom that the Aramaic translators brought to their work seems to suggest that the Bible was

not

regarded as so sacrosanct that it could not be imaginatively rewritten and reinterpreted.

The Bible was also translated into other languages of the ancient Near East, and some of these translations are still regarded as authoritative by various churches in our own times. The Samaritans, a people who split off from the Israelites in antiquity, have preserved their own version of the Pentateuch, including an original Hebrew text and various translations into Aramaic, Arabic, and Greek. An ancient translation of the Bible into the Syriac language, a form of Aramaic, is still used by the Syrian Orthodox and Maronite churches, and an early translation of the Bible into the Coptic language is still used by the Coptic Orthodox Church. These and other early translations of the

Bible illustrate that the biblical text has been preserved in a great many different forms—one scholar, for example, counted some six thousand textual differences between the Masoretic Text and the Pentateuch used by the Samaritans.

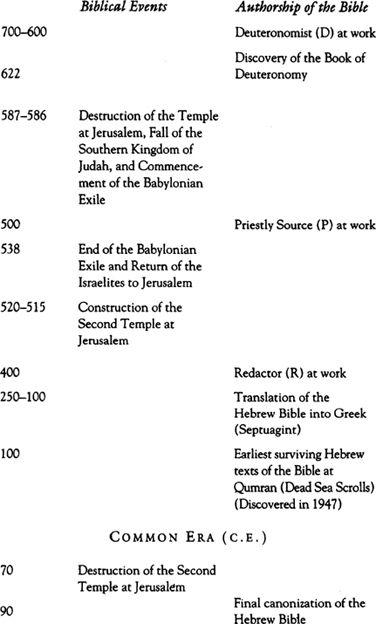

The first translation of the Bible into Latin was the Vulgate, which was completed by St. Jerome at the direction of the Bishop of Rome at the beginning of the fifth century C.E. The Latin text of the Vulgate was relied upon by some of the earliest translators of the Bible into European languages, including English. Only after the revival of ancient languages and the retrieval of ancient writings during the Renaissance did Western European scholars go back to the original texts of the Bible in Hebrew and Greek to create their translations.

The familiar words and phrases that strike most readers as “biblical” are found in the so-called King James Version, a Shakespearean-era English translation of the Bible by fifty or so Anglican clerics who completed their work at the behest of King James I in 1611. The so-called KJV has been revised extensively over the centuries—and has been replaced in many churches by contemporary translations—but the ringing phrases of the original text can still be found in many English-language Bibles, including the 1917 Jewish Publication Society translation of the Masoretic Text that I have used as my “proof text” in this book.

Although the King James Version is a fundamental work of Western literature, it has come to be regarded as passé and politically incorrect in many circles nowadays. Some modern translators are much more forthcoming about the “forbidden” elements of the Bible than the KJV—the superb Anchor Bible, for example, offers fresh and lucid translations of both the Hebrew and the Christian books of the Bible and explains the real meanings of the biblical text in line-by-line annotations. Still, the newer Bible translations that have replaced the stately old KJV have not matched its grandeur and resonance of language. The new translations are more accurate in their scholarship,

more forthcoming in their exploration of history, linguistics, and theology, but something has been sacrificed in the process.

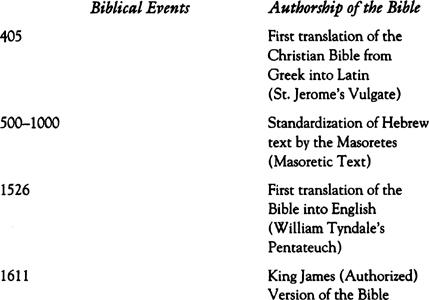

Here is a comparison of Genesis 1:1–3 as it appears in a 1909 edition of the King James Version and two more recent renderings of the Hebrew text.

| King James Version (1909) | New English Bible (1970) | New JPS Translation (1985) |

| In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void; and dark… ness was upon the face of the deep, and the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light; and there was light. 6 | In the beginning of creation, when God made heaven and earth, the earth was without form and void, with darkness over the face of the earth, and a mighty wind that swept over the surface of the waters. God said, “Let there be light,” and there was light; and God saw that the light was good, and he separated light from darkness. 7 | When God began to create heaven and earth-the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surfaces of the deep and a wind from God sweeping over the water—God said, “Let there be light” and there was light. 8 |

Since the debate over the proper approach to biblical translation is an old, contentious, and highly technical one, I will not belabor it here except to invite the reader to ponder which of the readings of Genesis he or she finds more resonant and meaningful.

ET

T

HERE

B

E

L

IGHT

A terrible price was paid by the courageous observers who first proposed that the Bible was written by human beings. Spinoza was excommunicated

by the Jewish community; the daring work of an early Bible scholar named Andreas Van Maes was banned by the Catholic Church; and the writings of a French Calvinist named Isaac de la Peyrere were burned. Even today, some true believers refuse to entertain the notion that men and women—merely mortal if also divinely inspired—put down the words on parchment and paper that so many seekers of truth all over the world regard as sacred.

What I have tried to suggest in this book is that some of the richest and most meaningful passages of the Bible—and some of the most instructive moral examples—can be found in stories that have been censored or suppressed precisely because they tell stories that are so deeply human. In a sense, then, the established religious authorities of all ages and all faiths have been far more comfortable with the notion that the Bible consists

only

of pristine moral pronouncements from on high and

not

the revelations of real men and women struggling with the messier challenges of life on earth.

Thankfully, however, it is no longer considered heresy to contemplate and explore the human authorship of the Bible—and, I suggest, the experience of reading the Bible is all the richer and more accessible if we do. “The sacred writer,” as the Catholic Church conceded more than a half century ago, may be properly (and even piously) regarded as “the living and reasonable instrument of the Holy Spirit.”

9

More recently, as we have already seen, Harold Bloom has put the same thought in slightly more secular terms, when he characterizes the Torah as no more and no less “the revealed Word of God” than Dante, Shakespeare, or Tolstoy.

So, even if we disagree on the outer limits of divine inspiration when it comes to the writing of books by mortal men and women, we all seem to start at the same place: the Bible.

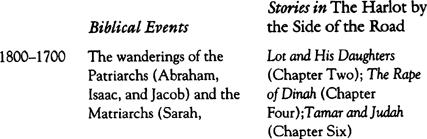

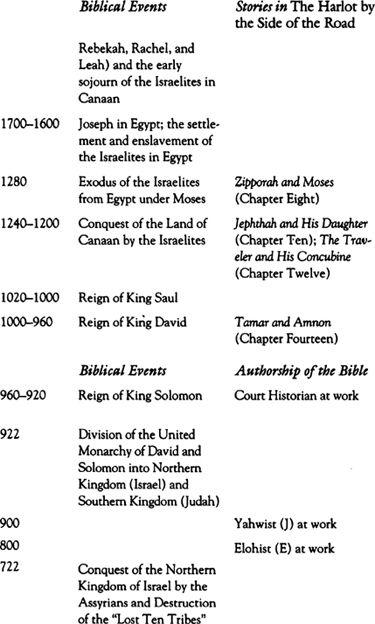

T

he dating of many events and works in early biblical history is the subject of much controversy among scholars, and thus all dating is approximate and, in many instances, speculative. I have adopted the designation Before the Common Era (

B.C.E.

) in place of the more familiar Before Christ (

B.C.

) to indicate events that occurred before the birth of Jesus, and the designation Common Era (

C.E.

) in place of Anno Domini (“In the Year of Our Lord,” or A.D.).

See

Recommended Reading and Bibliography

for complete citations.

CHAPTER ONE

1.

Susan Niditch, “The Wronged Woman Righted,”

Harvard Theological Review

72, nos. 1-2 (January-April 1979): 149.

2.

Marvin H. Pope, “Euphemism and Dysphemism in the Bible,” in

The Anchor Bible Dictionary

, 6 vols., ed. David Noel Freedman (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1992), vol. 1, 725.

3.

Pope, ABD, vol. 1, 725.

4.

G. Vermes, “Baptism and Jewish Exegesis,”

New Testament Studies

4 (1957-1958) (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1958): 314.

5.

Ralph Klein, “Chronicles, Book of, 1-2,” in ABD, vol. 1, 997.

6.

Robert Gordis,

The Biblical Text in the Making

(Philadelphia: Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1937), 30.

7.

Pope, ABD, vol. 1, 721.

8.

Pope, ABD, vol. 1, 722.