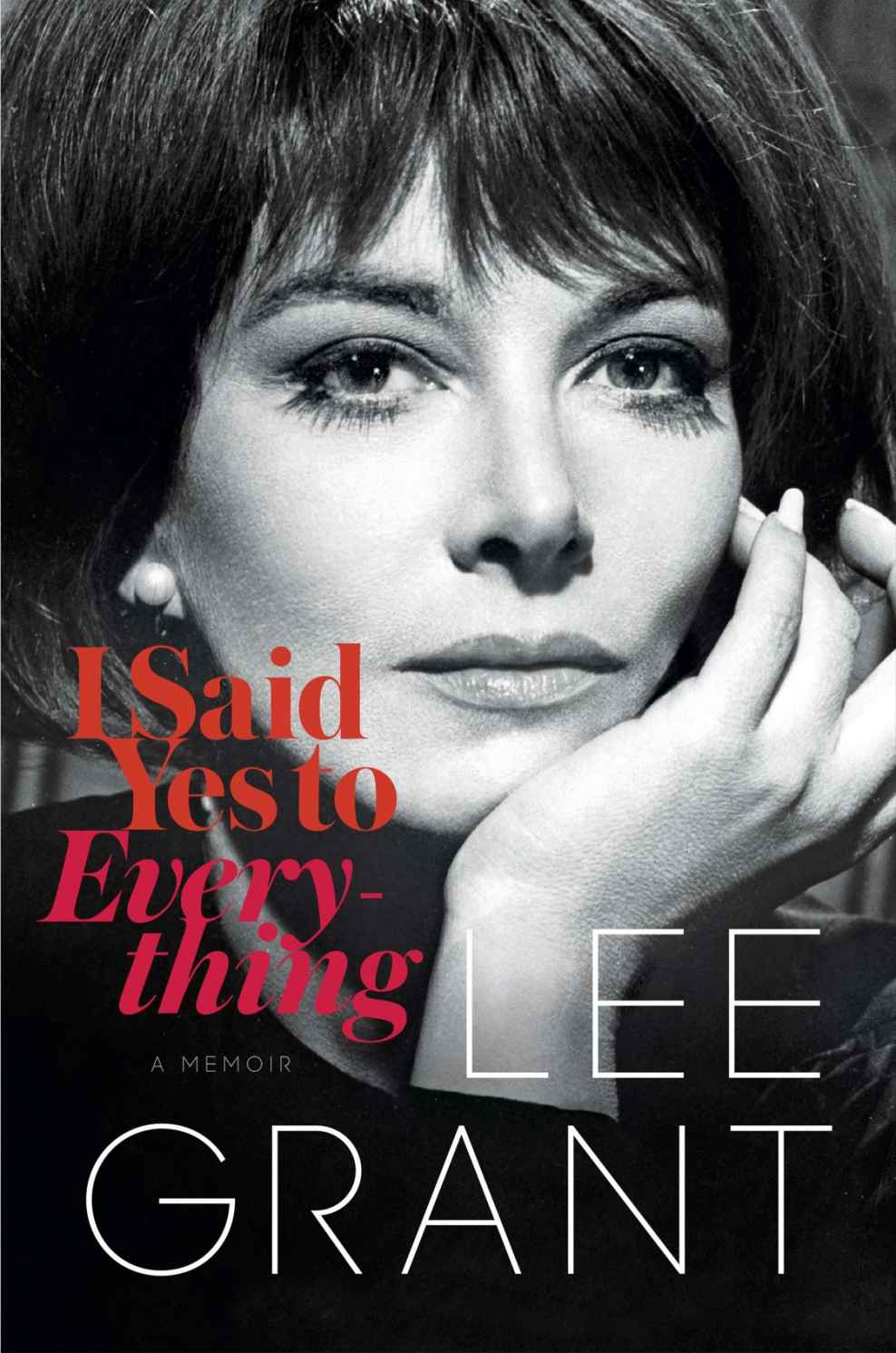

I Said Yes to Everything: A Memoir

Read I Said Yes to Everything: A Memoir Online

Authors: Lee Grant

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA • Canada • UK • Ireland • Australia • New Zealand • India • South Africa • China

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright © 2014 by Lee Grant

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grant, Lee, date.

I said yes to everything : a memoir / Lee Grant.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-698-15511-4

1. Grant, Lee, date. 2. Actors—United States—Biography. 3. Motion picture producers and directors—Biography. I. Title.

PN2287.G6753A3 2014 2014011916

791.4302'8092—dc23

[B]

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

Version_1

I dedicate this book to

Joey,

to Dinah and Belinda and their families,

Phyllis,

and

to my mother, father, and Aunt Fremo.

The First High School I Was Asked to Leave

My Parents Demand to Meet Arnie

The Public Theater and

Peyton Place

Plaza Suite

and

The Prisoner of Second Avenue

Charlie Chan and the Curse of the Dragon Queen

Directing Theater for Joe Papp

Burt Bacharach to Elizabeth Taylor

A Father . . . A Son . . . Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

O

nce, when I was little, I dreamed that I could fly. I dreamed that when I breathed in, I flew upward, weightless, above the heads of all the children in the granite playground. When I breathed in I went up, up, up; when I breathed out I could swoop down and touch the tops of their heads. I swirled gracefully in the air, in my brown winter coat with the velvet collar from De Pinna’s. I woke up so excited that I threw off my blanket and ran from my bed to the window in my bedroom. I threw the window open and climbed onto the radiator cover. The birds were flying outside. I would join them. I spread my arms, and from the seventh floor I saw the sparrows swooping toward the concrete below. Suddenly I saw myself smashing beside them. It shocked me, and I was afraid of myself and how easily I could fool myself into disaster.

I climbed down from the radiator. My mother opened the door. “Who opened the window?” she said. “It’s cold in here.”

• • •

I

’ve experienced that sense of exaltation and intensity in my life many times: in adolescence, when the boys made my heart pound; in acting, when I jumped without a net, and flew, and turned, and

believed for those few hours that I inhabited another’s life, and experienced new joy and pain. I’ve felt safe in flight, in love, in sex, and with those who flew with me.

I’ve also jumped and died, not once, but many times, unwisely and impetuously. I flew into fame as a very young Broadway actress, then jumped (through my first husband) into the Communist Party, only to find myself blacklisted for twelve years. I’ve reinvented myself many times over, picked up my broken wings and flapped till I could hop around again.

I’m flying again now, in my bedroom, writing, looking out my window. I had no idea, until I began putting pen to paper, that so many memories were inside me waiting to be rediscovered. I’m very lucky. I may even come to know myself.

M

y mother’s job was to mold me into her American Dream.

Didn’t young Witia from Odessa expose the child in her belly to every art museum in New York City, every day that she could carry me on her long legs? The magic of transformation was real in her young life. The Jewish child hunted in her cellar by goyim on horseback was transplanted to a new land where anything was possible, if you made it happen. And she wanted to make it happen for her daughter.

Witia was determined to plunge her hands into my baby fat and model me into a superior, beautiful being, who would either marry rich or rise above all others in the arts: ballet, theater.

There was no question about it.

• • •

M

y father was born in the Bronx, the youngest son of Polish Orthodox Jewish immigrants. His brother and sisters were ambitious. His brother, Aaron, and sister Anne were show business lawyers.

My father, Abraham, was the good son, the good man. He graduated from Columbia, where he had studied economics with John

Dewey and was on the wrestling team. He kept a neat, tight, muscular body all his life. He bent his head over the radio every Saturday afternoon to listen to the Metropolitan Opera. He loved coloraturas. My father was the director of the Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association of the Bronx. It was a position of great responsibility, great dignity. He was the moral compass of the family.

My grandfather went to shul every day. His tiny wife, Ida, kept an Orthodox home. They lived in a clean, old apartment on College Avenue in the Bronx. Their children must have supported them, because my grandfather never left the shul for his hardware store. But they and America raised smart, goal-oriented children.

The story goes that my mother went to the Bronx Y to get a job giving classes in dance. She had just graduated from college, where she majored in movement in the Isadora Duncan tradition. I have pictures of her from school. She was beautiful—five feet seven, straight back, long shining dark hair, hazel eyes. When she smiled, her top and bottom teeth glistened like a Spanish dancer’s.

She sat in the chair in my father’s office, reciting her qualifications for the job. She was rocking in the chair, nonchalant, when she did one rock too many. The chair tipped over and she landed on the floor. My father came from behind his desk, laughing, and helped up my flustered, embarrassed mother. And that. Was that.

My mother’s name was Witia Haskell, Americanized from Vitya Haskelovich. Her mother, Dora, had five children—three boys, Joseph, Raymond, and Jack, and two girls, Witia and Fremo. I never knew my grandfather Leon, for whom I was named. He was a clothing designer and a committed Zionist who left for Palestine with several other Zionist men before I was born. He must have done well, because he bought the brownstone on 148th and Riverside Drive before he returned to Palestine to establish a Jewish state.

They all died of malaria while fighting for their cause. There is a

plaque in Rishon LeZion with his name on it. In Russian

Leon

is

Lyov

, as in Lyov Tolstoy, Leo Tolstoy. My name is Lyova. There is no such name in Russian. Try being a Lyova in a world of Bettys and Judys and Emilys and Janes.

Position your tongue for an

L

, then say

yaw

, then

vah

. In high school I changed the

V

to an

R

and Lyora, pronounced

Leora

, was born. Hence Lee.

From the time I can remember remembering, I was my mother’s beloved thing, little girl, petted, brushed, combed, bathed, fed, beautiful, lived through. Her life. Her lovely sweet breath. The light in her hazel eyes.

• • •

I

woke up this morning dreaming about my childhood on 148th Street. I’d learned early on from my mother that some of the women in my father’s family had made my mother’s life so miserable, had criticized her and picked on her so much, that she didn’t know where to turn. And her husband, my father, refused to take sides or defend her. The mean women in my father’s family, the Rosenthals of Poland, thrived on attack, thrived on gossip. My mother didn’t have a chance. There was no mean bitch in her Russian genes. She took me to my grandmother’s brownstone on 148th Street to live. I must have been three or even younger when she and my father separated.

We lived at 620 West 148th Street between Riverside Drive and Broadway until I was six. My mother and I slept on the bird’s-eye maple beds in the big bedroom on the second floor, with an ornate white potty underneath. There was no bathroom on the second floor. On the ground floor was the Haskell Nursery School that my mother and her younger sister, Fremo, ran.

In summer the Haskell Nursery School was a busy, humming place. All the attention wasn’t on me. Fifteen or so little children from

the neighborhood arrived every morning. One morning, as I opened the door, one of them asked me, “Does everyone call you Lovey because they love you so much?” A lurch went through me. Is this what love is? A new word, a new concept.

In warm weather there were games in my grandmother’s house with children, painting with Fremo, and being wild and free in the backyard. In winter the children didn’t come and I was pushed alone into an empty, cold yard in my ugly orange and brown snowsuit, the first snowsuit on the block, my mother told me. I was bored much of the time. Bored and lonely. I had two ratty baby dolls with cloth bodies that I felt really close to. Their eyes, blue of course, opened and closed.

I fell inside myself as an only child. Other children were the holy grail—I longed for little girls to play with. My Aunt Fremo was a girlfriend. She was a grown child, delightful, peculiar.

Mostly I was coddled, and bored, and observant. I was participant and audience. I was steered into dance, given books, which I read and read. I listened. To Mother and Fremo. I was sleeping awake, doing what I was told.

• • •

I

n winter I climbed up to the window and pressed my forehead to the cold pane. I could see our cement yard with its one big tree in the middle.

Our house was full. Uncles Joe, who became a lawyer in Great Neck, and Raymond, who worked for the post office, and Jack lived there, Fremo, Grandma, Mother, and me. I was four. My uncles, especially Joe, teased me and played jokes on me. After my bath, when I was naked. They teased me about my behind when I clutched the towel in front of me. When I covered my behind they teased me about my front. They laughed deep men’s laughs, especially Uncle Joe.

My childhood was a waiting period, cocoon-like and plump. I don’t remember any strong feelings. I was a not-unwilling lump, but watching carefully.

I was not allowed to play on the streets with the exciting and exotically normal children. Right next door was the mysterious huge white apartment building 706 Riverside Drive, which contained all the children I longed for. It also contained Mrs. McCarthy and her handsome twenty-year-old son, John.

My mother allowed me to visit Mrs. McCarthy in her apartment by myself. I would sit on the footstool, looking up at her. She sat in the armchair opposite me. There, with the shades half-drawn, she would pour out her fears and concerns for her son. John was a drinker. Her pale face was crumpled in sadness and worry. Her sad, limp fingers played with a hankie, and she poured her heart out to me. I loved it. I loved Mrs. McCarthy. I loved her for raising me out of the oatmeal plainness of my days. Her stories were moving and thrilling. John was the center, the hero, the villain, the love of her life, lost to her now. Once, the front door opened. “That’s him,” she said, tightening her hand on my arm. It was midafternoon. A tall, dark-haired young man entered, a little off balance. I remember his head coming down to mine, the gray eyes crinkling, the white smile and pink cheeks. He must have said “Hello there” and gone off to his room. Mrs. McCarthy’s hand was tight on mine. I understood everything.

Her John reminded me of my Uncle Jack, who lived on the top floor. Jack was younger than John, but also handsome and funny, and he teased me and made me laugh as if I were tickled. I wasn’t allowed to enter Uncle Jack’s room because he had TB, but I would climb to the top of the stairs and run down again. It was our game—he sitting in bed on his white sheets cross-legged, me running up to his open door and down the staircase. Jack died when he was twenty-one. I’m crying as I write this, thinking of his lonely spirit trapped on the fourth

floor. Mother said he was in the sky with the stars. She took me to the window and pointed at the purple sunset. It made no sense to me.

Mrs. McCarthy gave me a book. It had caricatures and illustrations of human foibles acted out by wonderful, outrageous cats. Men cats in camel-hair coats, lady cats dripping with pearls in compromising positions. I got it. The cat book disappeared one day. My mother must have opened the pages. I wasn’t allowed to visit Mrs. McCarthy anymore.

I missed Mrs. McCarthy. She trusted me. She didn’t treat me like a five-year-old but saw the person I could be. I worried about her for a long time. Maybe it was she who opened me to the fear and pain of others. Maybe it was my Uncle Jack.

My heart aches for us all. The lonely only child; the beautiful immigrant mother responsible in her heart for everyone in our house. Her dreams for me, and her protectiveness, would result in an explosion of rebellion from her only child that almost destroyed her.